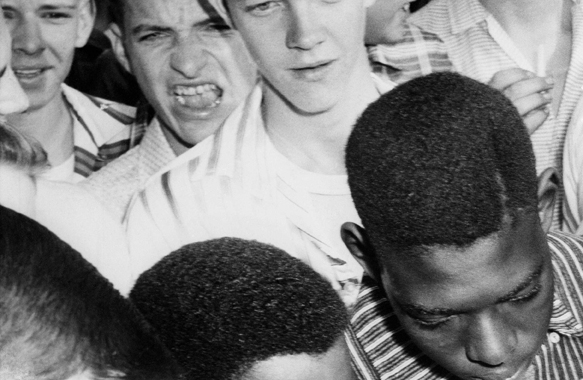

Photograph; Sam Greene | Dispatch | The school on S. 6th Street is one of four Olympus schools shuttered.

Felony theft, filth, and failure to meet payroll, and still, the public funds keep coming. A sponsorship is all you need and regardless of your record you too can become a Charter School founder. Your doors will remain open and the children will keep on giving, but let enrollment numbers fall and you will not be forgiven! Such is the state of the Ohio Charter School union. “A couple of players with standards that are not up to par,” will spoil the bunch, or perhaps add to the confusion. Should the 134 charters ever been opened? Were the closures predictable? Will the taxpayers’ recover their millions? Sure precious time was presumably wasted; but what of the minds of our children? Should there be a proposal for possible fines? Maybe. And might that too be brushed aside as … “It’s a hazard of the business”?

Schools closing at alarming rate, costing taxpayers and disrupting the lives of hundreds of students

At the beginning of 2013, one long-struggling charter school closed. Over the summer, five more did. And in the fall, 11 more Columbus charters closed their doors, most of them brand new.

That’s 17 charter schools in Columbus closed in one year, which records show is unprecedented.

“It shows the power of a couple of players with standards that are not up to par really affecting an overall market,” said Chad Aldis, a vice president at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, which sponsors 10 charter schools in Ohio, some in Columbus.

Nine of the 17 schools that closed in 2013 lasted only a few months this past fall. When they closed, more than 250 students had to find new schools. The state spent more than $1.6 million in taxpayer money to keep the nine schools open only from August through October or November.

But while 2013 was unusual, closings are not rare. A Dispatch analysis of state data found that 29 percent of Ohio’s charter schools have shut, dating to 1997 when the publicly funded but often privately run schools became legal in Ohio. Nearly 400 currently are operating, about 75 of them in Columbus.

It took 15 years for Ohio’s list of closed charters to reach 134; then that number grew by almost 13 percent last year from charters closing in Columbus alone.

Before 2013, only three had closed within half a year of opening, and the median life of a charter was more than four years. (Because information is missing, The Dispatch couldn’t calculate how long 12 schools stayed open.)

“Enroll Now” banners still hang outside some of the closed charters. Suspension notices or new “ for lease” signs are posted at others.

Among the nine new schools that closed abruptly, money troubles were a common theme. Some were forced to close because of health and safety problems — students weren’t getting nutritious lunches, or the buildings were unsanitary. Others chose to close because they were unable to meet payroll or were forced to close by their sponsors.

Looking back, some in the charter-school community and at the Ohio Department of Education question whether some of the new schools ever should have opened. How, they wondered, did this happen?

Many point to the sponsors. Nonprofit groups, universities, school districts and educational service centers can act as charter-school sponsors or authorizers. They’re supposed to be the gatekeepers; they decide which schools can open and whether they should close if they’re not adequately serving students.

“The way it works right now is, if a school has a sponsor and they sign a contract, that school can open,” said John Charlton, spokesman for the Ohio Department of Education. “We don’t have any approval or denial power.”

Five of the nine schools that opened and then closed abruptly in the fall were sponsored by the North Central Ohio Educational Service Center, based in Marion and Tiffin. The ESC appears to have lacked a rigorous vetting process.

The ESC, which provides staff members and other types of services to school districts, gave the go-ahead to Andre Tucker to open two Talented Tenth Leadership academies. They opened in August. In October, after the state pointed out serious problems, the ESC forced the schools to close.

It turned out that Tucker had been charged with felony theft and ordered to pay restitution in Florida and had money problems with an earlier charter school.

“If we had known the concerns that have been exhibited by the Talented Tenth Leadership programs, we would not even have attempted to sponsor them,” said Jim Lahoski, superintendent of the ESC. Tucker has said the ESC is to blame for his schools’ failure. He is suing the ESC.

At another ESC school, First Time Learners Academy, the founder got into a dispute with a contractor and other employees. Enrollment was too low. The state said conditions there were unsanitary. The ESC ordered it to close.

“We had a lot of hope for some of the schools. And then, when it came down to crunch time, they were not able to get the numbers,” Lahoski said.

That was the problem with the four Olympus High Schools opened here by a superintendent who also had run into trouble at a previous charter school. Not enough children enrolled, and the schools opened late.

Lahoski said he thinks the charter-school market in Columbus is saturated. There are 16,300 children from Columbus City Schools attending charter schools and thousands more from suburban school districts.

Every time a headline this past fall announced that another charter was closing in Columbus, operators of the ones that do well say they groaned.

“Charter-school failures erode the public’s confidence in our movement as a whole,” said Andrew Boy, who runs the two Columbus Collegiate Academy schools, which have attracted a lot of attention for their success with middle-school students. “Like it or not, all public, independently operated charter schools are grouped together.

“All considered, I despise sponsors who continually let well-meaning individuals open schools who have no business doing so.”

There also can be great cost to children and to taxpayers when schools close.

“A school goes belly up, and the public is out the money, and the kids’ educational programming has been harmed,” said William L. Phillis, the executive director of the Ohio Coalition for Equity and Adequacy of School Funding. He has been critical of charters.

Since 2000, when the state auditor began auditing charter-school finances, 110 schools have been found to have misspent a total of $22.6 million. Many of them are closed.

It isn’t yet known whether any of the schools that closed in 2013 misspent money; audits will be conducted. It is difficult to recover misspent money, however.

The Ohio attorney general often sues to recover withholding taxes or retirement payments. But there are few assets, if any, once schools close.

Advocates and critics alike say one way to avoid a rash of closings such as the one Columbus experienced late last year is to do a better job deciding who should be allowed to open.

“You can always do your very best — nobody has a crystal ball — but there’s a lot of things we do as a sponsor that we try to really do our due diligence, to do our homework,” said Frank Stoy, director of contracts and operational support for the Ohio Council of Community Schools, a nonprofit group that sponsors 51 schools in Ohio. The state points to it as an example of a top-notch authorizer.

Lahoski of the ESC said he will do “a better job of scrutinizing the candidates” who want to open charters under his ESC’s oversight in the future.

But of the closings, he said he doesn’t think the ESC is particularly at fault. It was a difficult market, and some of the operators simply weren’t ready to handle running a school.

“It’s a hazard of the business,” he said.

jsmithrichards@Dispatch.com

@jsmithrichards

bbush@Dispatch.com

Leave A Comment