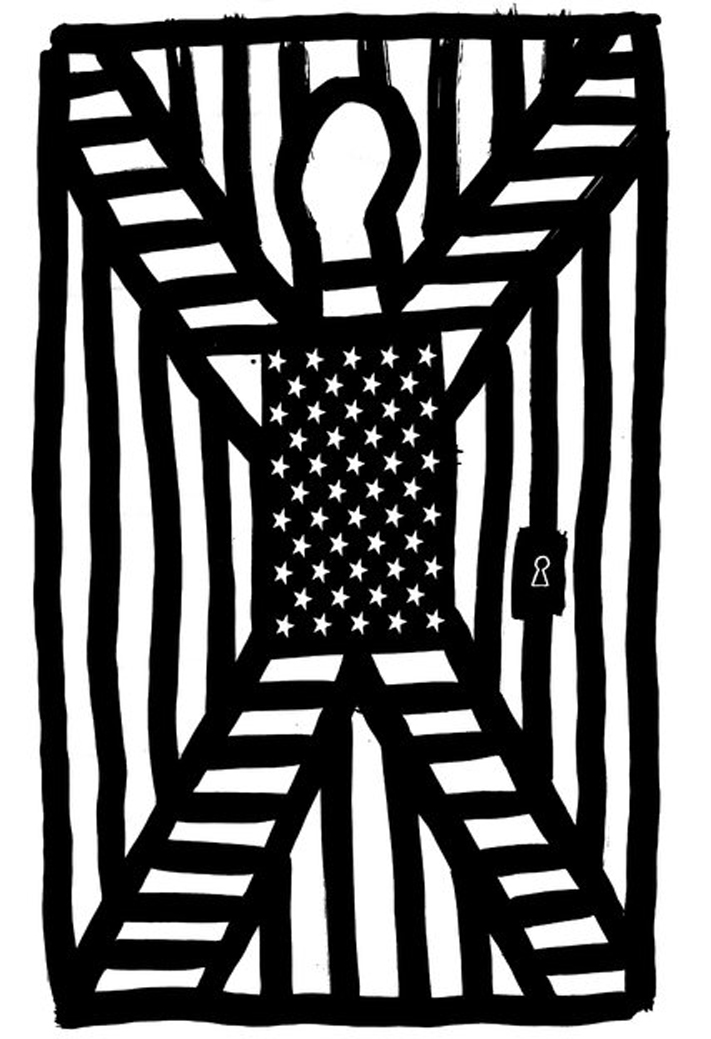

By Nicholas Turner and Jeremy Travis | Originally Published at The New York Times. August 6, 2015 | Illustration Credit; Jan Bajtlik

The men serving time wore their own clothes, not prison uniforms. When entering their cells, they slipped out of their sneakers and into slippers. They lived one person per cell. Each cell was bright with natural light, decorated with personalized items such as wall hangings, plants, family photos and colorful linens brought from home. Each cell also had its own bathroom separate from the sleeping area and a phone to call home with. The men had access to communal kitchens, with the utensils a regular kitchen would have, where they could cook fresh food purchased with wages earned in vocational programs.

We hoped that we were getting a glimpse of what the future of the American criminal justice system could look like.

This is an encouraging moment for American advocates of criminal justice reform. After decades of callousness and complacency, the United States has finally started to take significant steps to reverse what a recent report by the National Research Council called a “historically unprecedented and internationally unique” experiment in mass incarceration. Congress, in a bipartisan effort, seems prepared to scale back draconian federal sentencing laws. Many states are making progress in reducing their prison populations. And President Obama, in a gesture of his commitment to this issue, last month became the first American president to visit a federal correctional facility.

But for all the signs of progress, truly transformative change in the United States will require us to fundamentally rethink values. How do we move from a system whose core value is retribution to one that prioritizes accountability and rehabilitation? In Germany we saw a potential model: a system that is premised on the protection of human dignity and the idea that the aim of incarceration is to prepare prisoners to lead socially responsible lives, free of crime, upon release.

While the United States currently incarcerates 2.2 million people, Germany — whose population is one-fourth the size of ours — locks up only about 63,500, which translates to an incarceration rate that is one-tenth of ours. More than 80 percent of those convicted of crimes in Germany receive sentences of “day fines” (based on the offense and the offender’s ability to pay). Only 5 percent end up in prison. Of those who do, about 70 percent have sentences of less than two years, with few serving more than 15 years.

The incarcerated people that we saw had considerable freedom of movement around their facilities and were expected to exercise judgment about how they used their time. Many are allowed, a few times a year, to leave the prison for a few hours or overnight to visit friends and family. Others resided in “open” facilities in which they slept at night but left for work during the day. Solitary confinement is rare in Germany, and generally limited to no more than a few days, with four weeks being the outer extreme (as opposed to months or years in the United States).

The process of training and hiring corrections officers is more demanding in Germany. Whereas the American corrections leaders in our delegation described labor shortages and training regimes of just a few months, in the German state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, less than 10 percent of those who applied to be corrections officers from 2011 to 2015 were accepted to the two-year training program. This seems to produce results: In one prison we visited, there were no recorded assaults between inmates or on staff members from 2013 to 2014.

Germans, like Americans, are greatly concerned with public safety. But they think about recidivism differently. During our visit, we heard prison professionals discussing failure in refreshingly unfamiliar terms: If, after release, an individual were to end up back in prison, that would be seen as a reason for the prison staff members to ask what they should have done better. When we told them stories of American politicians who closed a work-release or parole program after a single high-profile crime by a released inmate, they shook their heads in disbelief: Why would you close an otherwise effective program just because one client failed?

To be sure, there are significant differences between the two countries. Most notably, America’s criminal justice system was constructed in slavery’s long shadow and is sustained today by the persistent forces of racism. The American prison-building binge was fueled by a political environment in which “tough on crime” was a winning campaign strategy.

But the German context still provides a vision of a possible American future. The first article of the German Constitution reads, “Human dignity shall be inviolable.” Granted, our own Constitution bans cruel and unusual punishment and protects individuals against excessive government intrusions. As was noted by the Supreme Court justice Anthony M. Kennedy in a landmark 2011 opinion ordering California to reduce its prison population: “Prisoners retain the essence of human dignity inherent in all persons. Respect for that dignity animates the Eighth Amendment.”

These words hold much promise, but currently they have far too little impact on actual conditions in American prisons. In Germany, we found that respect for human dignity provides palpable guidance to those who run its prisons. Through court-imposed rules, staff training and a shared mission, dignity is more than legal abstraction.

The question to ask is whether we can learn something from a country that has learned from its own terrible legacy — the Holocaust — with an impressive commitment to promoting human dignity, especially for those in prison. This principle resonates, though still too dimly at the moment, with bedrock American values.

Nicholas Turner is the president of the Vera Institute of Justice. Jeremy Travis is the president of John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

A version of this op-ed appears in print on August 7, 2015, on page A27 of the New York edition with the headline: What We Learned From German Prisons.

This piece was reprinted by EmpathyEducates with permission. We thank the Authors, Nicholas Turner and Jeremy Travis for their kindness and their humane and welcome wisdom. We are grateful for what we believe invites a vital reflection. Perhaps, it is time to look at our prisons and see what is locked-away or hidden.

Leave A Comment