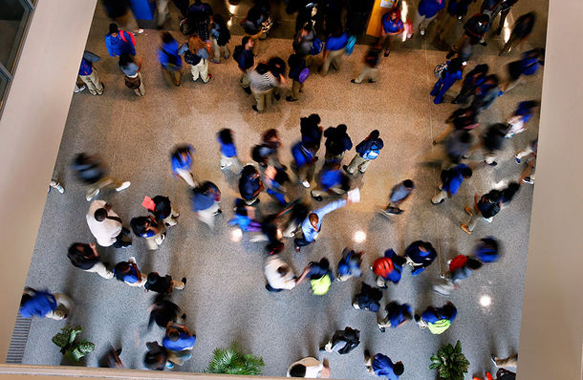

Students change classes during the first day of school at Landry-Walker High School on August 12, 2013. (Photo by Kathleen Flynn, Nola.com / The Times-Picayune)

Introductory Reflection by Raynard Sanders, Ed.D., Host of The New Orleans Imperative

In this week’s Louisiana Weekly’s article

In the article Kari Harden interviewed Leslie Jacobs and confronted her on the consistently low academic performance of RSD in the article she stated the following:

“Asked about the RSD’s persistently low rankings after close to nine years, Jacobs said that the question about the success of an all charter district doesn’t relate to performance, it instead relates to “system and governance.”

This unbelievable given Leslie Jacob’s annual and daily touting of the “unprecedented academic success” of the reforms post Hurricane Katrina on her web site, numerous interviews to the media and to conferences all over the country for the past 9 years.

The architect of ACT 35 and Mother of the Recovery School District is “finally” admitting to its academic failure!!

IT’S ABOUT TIME!

UNBELIEVABLE!!

New Orleans Nearing a ‘Privatized’ Public School System

As the Recovery School District (RSD) shuts the doors on its remaining handful of traditional public schools, the start of the 2014 school year will usher in the nation’s first completely privatized public school district.

Every school the RSD took over following Hurricane Katrina and the passage of Act 35 — with the stated intent of “turning around,” was either closed or will be turned over—into the hands of private charter operators, creating the first all-charter district in the history of the United States.

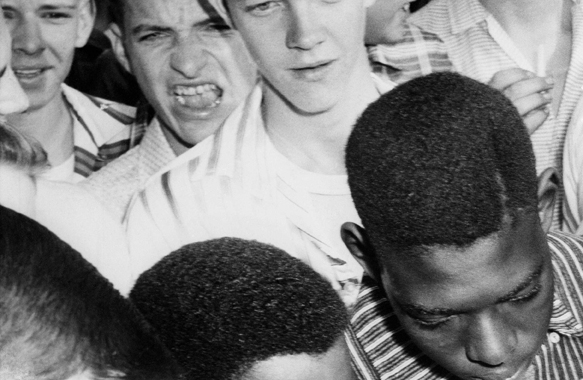

For nearly nine years it has been on the backs of New Orleans’ children and communities that the “reformers” have conducted this grand experiment, the majority of whom have come from other parts of the country.

Now, as the “reform” train, (fueled by billionaire philanthropists and Wall Street investors), plows across the land, the nation looks to the New Orleans test site. Anyone and everyone concerned about the education of American children and the future of the country must ask: Did it work?

The grandiose public relations campaign put forth by the Louisiana Department of Education and the RSD suggests a resounding “Yes!” But lawsuits alleging the wrongful termination of teachers and the discrimination against children with special needs, civil rights complaints alleging prison-like conditions and racial discrimination, and disenfranchised communities full of devastated and angry alumni who have watched neighborhood schools ripped away – schools that were at the core of their identity for generations – all suggest otherwise.

And while the local mainstream media seems all too happy to gobble up and regurgitate the state’s academic achievement data as truth, the blogosphere is abounding with carefully documented details of the state’s systemic and persistent manipulation – and illegal withholding – of public data.

Even by the state’s own haphazard standards, the now all-charter RSD New Orleans continues to remain at the bottom of state rankings. In 2012, the RSD was given a “D” letter grade.” In 2013, the RSD was given a “C” – still within the state’s own definition as failing in terms of voucher eligibility.

However the “C” also must include the following footnote: By changing the formula and scale from 2012 to 2013, the state essentially changed the standards and, in what public school teacher and blogger Mercedes Schneider calls “charter churn,” artificially inflated the scores.

Upon a painstaking examination of the state’s data, Schneider, who also authored the whistle blower book “A Chronicle of Echoes,” wrote that “Of the 37 RSD-NO schools with complete 2012 and 2013 SPS/letter grade information, 26 increased a letter grade as an artifact of John white’s changes to the scoring system. . . In other words, had the same rules applied in 2013 as were applied in 2012 to grading RSD schools, then 15 schools would have received a “D” instead of a “C”; five would have received an “F” instead of a “D,” and five would have received a “C” instead of a “B.” Had consistent criteria been used in grading RSD-NO from 2012 to 2013, its district letter grade would have remained a “D.”“

It is that same self-appointed power to change standards to achieve political objectives that allowed the RSD to take most of New Orleans’ schools in the first place. The tale of the nation’s first all charter district must begin with the political forces that were waiting in the wings to take advantage of a hurricane to wipe out everything that existed before the storm — also known as Act 35.

The takeover of 107 New Orleans public schools could not have happened without first changing the state’s definition of a “failing” school, and the mass firing of more than 7,000 employees, including about 4,500 teachers.

Before Hurricane Katrina, the RSD (created in 2003) could only take over a school with a performance score less than 60, and which had already gone through four years of corrective action.

To legally justify taking the majority of New Orleans schools and then privatizing them, the state changed the failing benchmark from 60 to just under the state average of 87.4.

The constant changing of grading scales and benchmarks has continued since, and has become an often scoffed at trademark of Superintendent John white’s dissemination of annual data.

There is widespread agreement that New Orleans public schools prior to Katrina needed help—they were sorely under resourced by the state and governed by a notoriously corrupt school board.

“There was a lot to be desired,” noted Dr. Raynard Sanders, but schools were making improvements.

Sanders has worked in education in New Orleans for more than 20 years as a teacher, administrator, principal, and professor. He currently works with local research and advocacy groups, and for five years has hosted “The New Orleans Imperative,” a weekly radio call-in show dedicated to education-related issues.

Prior to Katrina, 80 percent of schools were meeting the annual yearly progress goals set by the state, Sanders said. Despite the lack of resources, shameful local politics, and “wrongheaded state policies,” schools were showing academic growth, he said.

Then the storm came, and Sanders said early on he saw it as “a great opportunity to change things systemically – to finally make public education equitable, and to create a learning environment to allow kids to reach their full potential.”

But, Sanders soon learned that there were some very powerful people who also saw an unprecedented opportunity for change.

“In many ways, New Orleans is a very good case study in terms of whether or not privatization works,” Sanders said.

According to Sanders, the “privateers” said they needed several things to turn around schools: to privatize the district, to eliminate unions, to get rid of bad teachers, and to have autonomy over curriculum.

Two critical goals of the new plan, he said, were to control resources, and dictate student populations — which students went to which school.

With Act 35, they got everything they wanted, including “exorbitant” amounts of both public and private money. They had media support, political support, and a traumatized population trying to rebuild their most basic aspects of their lives. “No where has it been done like in New Orleans,” Sanders said.

The privatization movement was spearheaded by businesswoman and former state and local school board member Leslie Jacobs, a pro-charter advocate and often referred to as the “architect” of the RSD.

Today, Jacobs sees a landscape in which parents are empowered by choice, and students are graduating at high rates (she cited 78 percent) and better prepared for college and careers than ever before.

Sanders sees the creation of one of the “worst performing school districts in the state,” one that “doesn’t like kids with special needs,” (as documented in the pending class action lawsuit), and a “disenfranchised and disrespected the community — particularly the poor and minority communities.”

Asked about the RSD’s persistently low rankings after close to nine years, Jacobs said that the question about the success of an all charter district doesn’t relate to performance, it instead relates to “system and governance.”

But performance does matter to Sanders.

To avoid the state’s convoluted and camouflaged data propagation, Sanders points to ACT scores. 2013 was the first year that all eligible public high school students were required to take the ACT.

In December 2013, education blogger Michael Deshotels wrote that: “It took a formal public records request to get our DOE to give me the ACT scores for 2013 by school and by local school system. I had been asking for the data informally for several months. These days it is almost impossible to get data from John white’s DOE without threatening a lawsuit.”

Deshotels continues, describing his findings and saying that he was not surprised at the department’s reluctance in releasing the scores: “The New Orleans Recovery District schools produced an average ACT score of 16.3 for the 2012-13 school year even though an analysis of the eligible students based on student enrollment data indicates that only about 80 percent of those eligible actually took the test. This average score of 16.3 by New Orleans RSD schools would not be high enough to allow a student to enroll in any Louisiana four-year college. This is ironic since many of the New Orleans Recovery District schools advertise themselves as college prep schools.”

The DOE listed the state average as 19.5, and just four parish public school systems scored lower than the RSD. “In addition,” Deshotels wrote, “I believe that if the New Orleans Recovery District had tested all eligible students, their average would have been even lower than the 16.3 reported.”

And on Jacob’s touted high graduation rate, Schneider wrote in that, “In this January 2013 reporting of ‘New Orleans’ school statistics, Leslie Jacobs plays a game with reporting a ‘New Orleans’ graduation rate” of 76.5 percent when the OPSB graduation rate was 93.5 percent. Remove that 93.5 percent boost from RSD, and the reality that a number of RSD high schools had embarrassingly low graduation rates (in the 40-60 percent range) shows all too clearly to sell the idea of RSD ‘success.’”

Sanders adds that the graduation numbers, despite numerous requests, “can’t be validated because the state won’t release the student data.”

On the notion of choice, Sanders said that prior to Katrina, parents could choose either the school in their attendance zone, or to get a permit to put their child in another school.

“Parents had more school choice pre-Katrina than post-Katrina,” he said.

Today, despite the claims that in the free-market system parents can vote with their feet, if a parent decides they want to move their child to a different school, they cannot do so after October 1.

Jacobs said that the October 1 policy (which she calls in the middle of the school year) is to “protect parents.” Jacobs also says that before Katrina it was extremely difficult to get permits — an assertion Sanders disagrees with.

Jacobs points to the OneApp unified enrollment system as a mechanism to level the playing field, allow parents to exercise choice, and keep schools from “gaming the system.”

But Sanders and a recent civil rights complaint claim that OneApp traps kids in failing schools. He also notes the problem of kids with special needs being assigned to schools that cannot provide the (legally required) resources. And without all schools participating in OneApp, there is no such level playing field.

Sanders calls the system undemocratic – with unelected boards controlling the money, the enrollment policies, the budget, and the hiring decisions.

A lack of genuine community engagement during the processes and policies through which the RSD seized and chartered the city’s schools remains one of the reform movements biggest criticisms.

Jacobs’ response to the system being undemocratic was that “It’s a myth to think that the public is engaged just because the board is elected.”

And on the lack of community engagement, Jacobs answered, “Show me a school in an urban district with an elected board which the community feels is responsive.”

Critics of the all charter system in New Orleans (with more than 40 mini-districts) also raise questions about sustainability and the efficient use of taxpayer dollars.

Jacobs said that the massive amounts of philanthropic money that poured into the city after Katrina has dwindled, and today is “significantly less.” The Walton Family Foundation money is “long gone” she said. To sustain, Jacobs said that some schools are getting “very good at fundraising.”

But Sanders sees the reliance on fundraising, especially for things such as football uniforms and band teachers, as unfairly passing along costs to largely already impoverished communities.

All the while, Sanders notes, the top-heavy administrations (many with their own Chief Financial Officers (CFO), Chief Operating Offices, principals for every grade level, etc.) are paying themselves salaries that are not only for positions that were nonexistence before Katrina (the entire district had one CFO) but also significantly higher than pre-Katrina.

Sanders cites John McDonogh High School, where Future is Now CEO Steve Barr collected an annual salary (subsidized by public grants) of $250,000 for a school with fewer than 200 students. Barr hired a principal for the 9th grade class of less than 20 students at an annual salary of $115,000. The academic payoff? An obscenely low school performance score of 9.3.

At Lusher Charter School, a selective admissions school criticized for cherry picking its students and then claiming success with their high scores, CEO Kathy Riedlinger makes an annual salary of $283,100, according to 2012 tax documents.

With six-figure salaries as the norm for the top administrators, a lack of accountability and transparency, and frequent instances of employees stealing, it is most certainly not efficient, Sanders said.

Jacobs did not respond to an emailed question about the financial efficiency of the all-charter system.

One of the few things that Jacobs and Sanders agree on is that the debate is not anti-charter versus pro-charter. Jacobs said it is about the varience of high-performing and low performing schools within the system.

Sanders acknowledges that there are some very good charters that are trying to stay true to the original intent of charter schools.

But instead of being inclusive of all students, Sanders finds that most charter schools are exclusive, especially of those students with greater needs coming in, and those that are more expensive or more challenging to educate, or aren’t predicted to score high on standardized tests.

The most common model is the zero-tolerance college preparatory charter school – schools with sky-high out of school suspension rates where students are forced to walk on taped lines, be silent during lunch and in the hallways, give respect unquestioningly to every adult, and partake in bizarre chants and rituals.

“There is more time put into making the kids follow directions and not question authority than into learning,” Sanders said, of the zero tolerance models, of whose discipline policies he calls “off the wall, senseless, and inhumane.”

The increasing amount of national data on the charter versus traditional school debate shows that on average, charter schools don’t have any academic advantage over traditional public schools. New research also shows that for the most part, charter schools lead to a risk of increased segregation.

The RSD refused a request for an interview for this story, and refused to provide answers to emailed questions about what an all-charter district means going forward in terms of the RSD’s role, and whether or not privatization was the intent from the beginning.

Sanders said he hopes that other districts will look at New Orleans as a case study recounting the failure of an all-charter district, which he describes as “private entities using public money and operating in public buildings.”

Sanders also points to the lowering of standards. At the time of the takeover, a school in New Orleans needed to have a performance score below 87.4 to be considered failing. Now, schools have to only have a performance score below 50 to be considered failing.

“Because of a lack of transparency and an untrained workforce, they dug a hole deeper than pre-Katrina,” Sanders said.

It’s a system where many of the schools take in only the most desirable students and then “create an economic opportunity for the people who operate the school,” he said. And many have been hurt in the process of experimentation, Sanders said, “because the rights of students and the sanctity of public education have been trampled on and forgotten about.”

For Jacobs, who cut the interview short, the questions about the success of an all-charter district are less about performance scores and more about governance, and creating a set of rules, such as centralized expulsion hearings, to keep the individual schools from “gaming the system.” “One school’s misbehavior affects the others,” she said. Jacobs believes without doubt that there are now more opportunities for all children in the city to get a quality education than existed pre-Katrina.

In New Orleans, the privateers got everything they wanted and more, and still failed, Sanders said. “It is a great case study, and also one of the biggest scams done on public education – and parents and students — in the history of the country.”

This article originally published in the June 2, 2014 print edition of The Louisiana Weekly newspaper.

Leave A Comment