Graph; Louisiana’s voucher program expanded statewide last year from a New Orleans pilot, gaining attention from the U.S. Justice Department. Legislative auditor Daryl Purpera said Monday there’s not enough oversight of the expanded (and expanding) budget. (Louisiana Legislative Auditor)

By Danielle Dreilinger | Originally Published at Times Picayune. on December 16, 2013 at 11:44 AM, updated December 16, 2013 at 1:37 PM

Louisiana’s controversial school voucher program doesn’t have enough safeguards to ensure participating private schools spend public money properly and educate the students they admit, legislative auditor Daryl Purpera said in a report Monday.

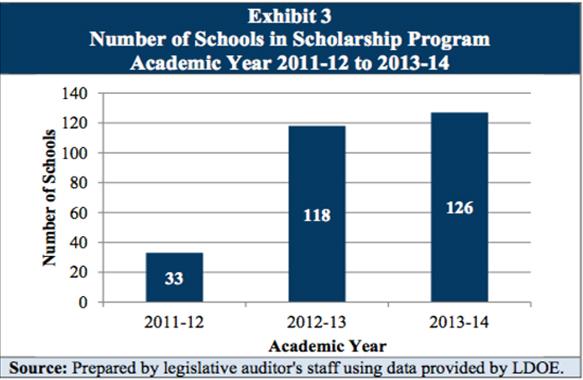

The Louisiana Scholarship Program lets some low-income students attend private school at taxpayer expense. In 2012-13, the first year the voucher program operated outside New Orleans, state spending increased from $8.9 million to $24.2 million on 118 schools. Half that amount went to schools in Orleans Parish, $2.5 million to Jefferson Parish and $3.6 million to Baton Rouge. Almost $45 million has been budgeted for the current school year, for more than 6,700 students.

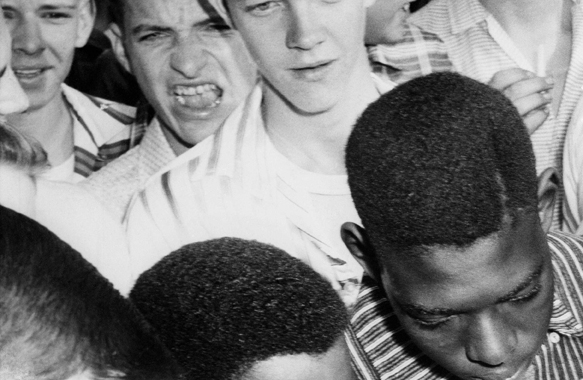

Gov. Bobby Jindal spent the fall defending Louisiana’s voucher program nationally after the U.S. Justice Department filed a petition charging it might worsen racial segregation in schools. Last month, a federal judge said the federal government has the right to monitor vouchers. The two parties are currently working on a plan for how that will work.

State Education Superintendent John White agreed with some but not all of the auditor’s recommendations. In a written response to Purpera, he said the Education Department has already strengthened accounting requirements for voucher schools and will spell out how it approves schools to take significant numbers of new students. However, he disagreed that the program needed to codify its procedures for booting low-performing schools from the program.

The Education Department had only a few months to implement the statewide voucher program after the Legislature passed the law in April 2012. The law, which was immediately challenged in court, gave only minimal requirements for how schools should be added and monitored. That summer, White added accountability measures: Schools that didn’t do a good job educating voucher students wouldn’t be allowed to stay in the program.

“The Louisiana Scholarship Program leads the nation in rigorous accountability standards,” White wrote.

Purpera disagreed and said the current policies weren’t enough, writing, “Without specific criteria, LDOE cannot ensure it is holding schools accountable for their academic performance and treating schools consistently.”

The state has faced challenges in measuring student performance, and Purpera criticized that. Only 22 schools had enough students in testing grades last year to calculate “cohort performance scores” — like a public school performance score but only for the students on vouchers, not the entire student body. One of those scores was not be released because of federal privacy laws against publishing information that might identify individual students.

Purpera pointed out that the accountability process is stricter for charter schools, which must post good test scores to stay in business.

The state was also largely unable to track voucher school spending in the first year, Purpera wrote. Independent fiscal auditors could fully examine only three of the 118 participating schools because most did not track their public dollars separately. One of those three schools, New Living Word in Ruston, overbilled the state $395,520 and has been removed from the program. White said the state attorney general’s office is pursuing reimbursement.

Purpera’s team found a number of schools with reporting errors that affected funds:

- Five schools requested vouchers for children whose family income exceeded the program’s limits. Four schools could not document family income.

- Almost one third of schools charged voucher students anywhere from $5 to $5,566 more than they charged private-paying students, which is not allowed.

- Ten schools could not provide home addresses for voucher students or had the wrong address. The dollar amount of a particular voucher depends in part on what parish the student lives in. That finding could also have ramifications for the federal case, which applies only to students and schools in the systems that are under long-running school desegregation orders.

Only six of the schools offered special education services. The auditor found half of them did not properly document those services and therefore might have overcharged the state.

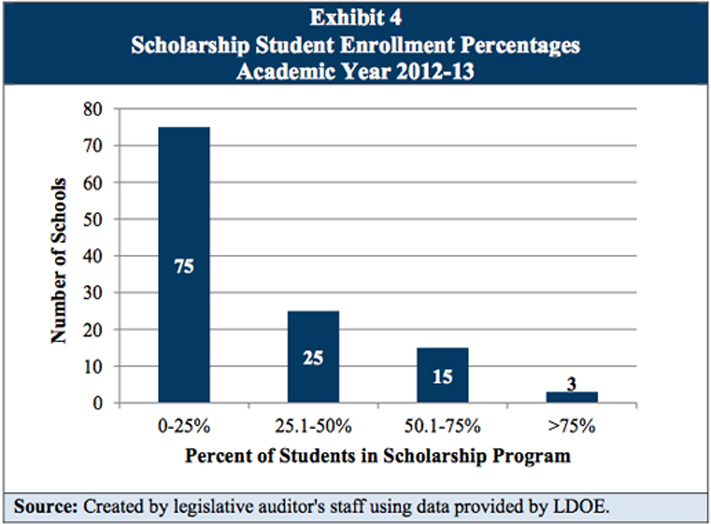

In 2012-13, at least half the student body was publicly funded at 18 private or parochial schools through the voucher program. The legislative auditor said Monday the state needed to spell out its protocol for allowing schools to take on a significant number of voucher students~ Louisiana Legislative Audito

As for the larger accounting picture, White said the Education Department is now requiring schools to track voucher funds separately even though state law doesn’t require it.

Finally, Purpera’s report says the state should “develop formal criteria for determining whether participating schools have both the academic and physical capacity to serve the number of scholarship students they request.”

For the program’s first year, half the voucher schools opened enough seats to boost their enrollment significantly, leading critics to say it was a money grab. At 18 schools, more than half the students were voucher-funded.

White also agreed with that recommendation. He said those schools did receive a thorough capacity review following internal procedures, which now will be set out in policy.

“The audit confirms that in the Scholarship Program’s first year, the state implemented the program according to the law,” White said Monday. “Most important, the program immediately offered thousands of low-income families a choice in where to send their children to school.”

He called some of Purpera’s suggestions “helpful.”

Leave A Comment