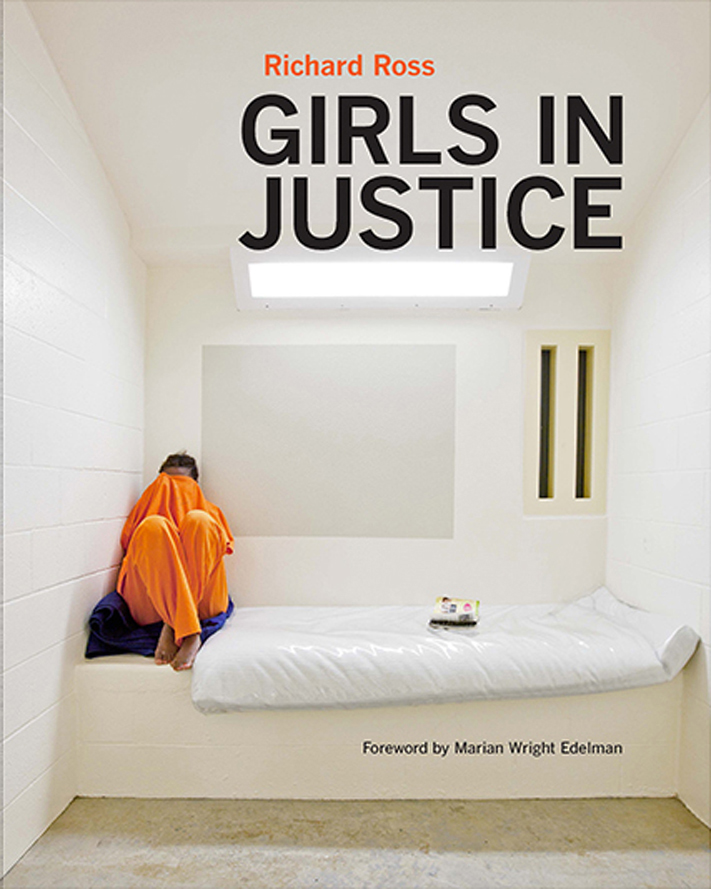

Project Description

''This is the story of not one girl, not two or three, ten, dozens, hundreds. It is the story of all the girls who are victims in a world that uses them, abuses them, and punishes rather than tries to treat or help them.'

It is the story of Girls In Justice and Injustices to Girls.

Stopping The Girls To Prison Pipeline

While overall arrest rates for juveniles have dropped nationwide, the rates for girls are falling more slowly or holding steady. For some offenses, the numbers are even trending up.1 In 2011, 429,000 girls were arrested nationwide and between 8,000 and 10,000 were locked up on any given day.2 Girls represent 29 percent of all juvenile arrests,3 up from 22 percent in 1986.4 Los Angeles County looms very large in the nation’s juvenile justice landscape, and in the lives of vulnerable girls.

There are painful realities in the lives of detained girls in California, and lethal flaws in juvenile correctional health care: 92 percent9 of girls have been sexually and/or physically assaulted and 88 percent have serious, in some cases life-threatening, physical and mental health problems.10 The Girls Health Screen study in 2009 found that sexual trauma was rampant. Over40 percent of girls undergoing medical intake into locked facilities had some form of vaginal injury.11 Approximately 22 percent had been forced to have sex, some within the previous seven days.12

Adding invisibility to injury, when girls are locked up their medical needs often go unidentified and untreated, drowned out by a correctional system designed for the larger population of boys.13 For complex reasons, there are no medical standards for girls in detention. In real life, this means that an incarcerated fourteen-year-old girl, in dire physical and emotional pain because she has been trafficked and forced to have sex with multiple older men, may be locked up for months without being able to voice her needs or receive medical help.

These numbers are so daunting that they could cause you to turn away.

I recently interviewed a girl in detention who was four months pregnant; her body was riddled with bullet fragments from when she’d been shot while trading sex for survival on the streets. Talking to her I felt admiration, not pity. Like so many other detained girls I’ve spoken to, she was vibrant, creative, pretty, and determined. She told me she planned to launch a website to help girls like her navigate a crime-free life as soon as she was released. Perhaps because I was a young mother when I met Donna, I’ve never lost track of the issues surrounding pregnancy behind bars. Between 20 percent and 30 percent of incarcerated girls nationwide have been or are currently pregnant.14 Yet in 2007 only 18 percent of the 3,200 locked facilities holding teen girls nationwide routinely tested for pregnancy.15 Even detention centers that do administer pregnancy tests to every girl who comes in—as they do in Los Angeles—are still designed and staffed to isolate and control. Rarely do they take on the role of nurturing or healing traumatized and pregnant teen mothers.

Today, pregnant girls behind bars still sleep in bare cells on thin green plastic mattresses set on concrete slabs. A pregnant fifteen-year-old may get more to eat than other girls—an apple, an extra plate of food for lunch— and receive daily prenatal vitamins, but when she goes into labor she is transported outside the lockup, under guard, to a local hospital to deliver. There, after a high-risk delivery (all teen deliveries are high-risk), her baby is taken from her, just hours after she’s given birth. Soon after that, she is returned to lockup to serve out the rest of her time. Alone.

Recently I visited a detention infirmary that housed a young girl who had just given birth. She was spiking a fever, possibly the result of a post-delivery infection. I wasn’t allowed to see her, but I heard that her infant, whom she’d been forced to relinquish at birth, was waiting alone in a hospital nursery for a family member or a social services representative to come pick him up. The young mother wanted to express her breast milk to feed her baby, but when I asked to see the nursing room all I saw, through a small dusty window in a locked door, was a rug and a chair. There was no nursing equipment.

I understand the complexities of huge correctional and health systems better than most, but I am deeply disappointed that in the years between Donna and today we have not found better and more humane ways to serve our most traumatized girls or protect their newborns. Despite recent and long-overdue attention to ending mass incarceration for men and boys, the national conversation still omits incarcerated girls. There are thousands more incarcerated males than females but women and girls’ smaller numbers in the system do not explain or justify their invisibility.

As one incarcerated sixteen-year-old girl wearing a bright pink T-shirt she had earned for good behavior told me, “We are not nothing!”

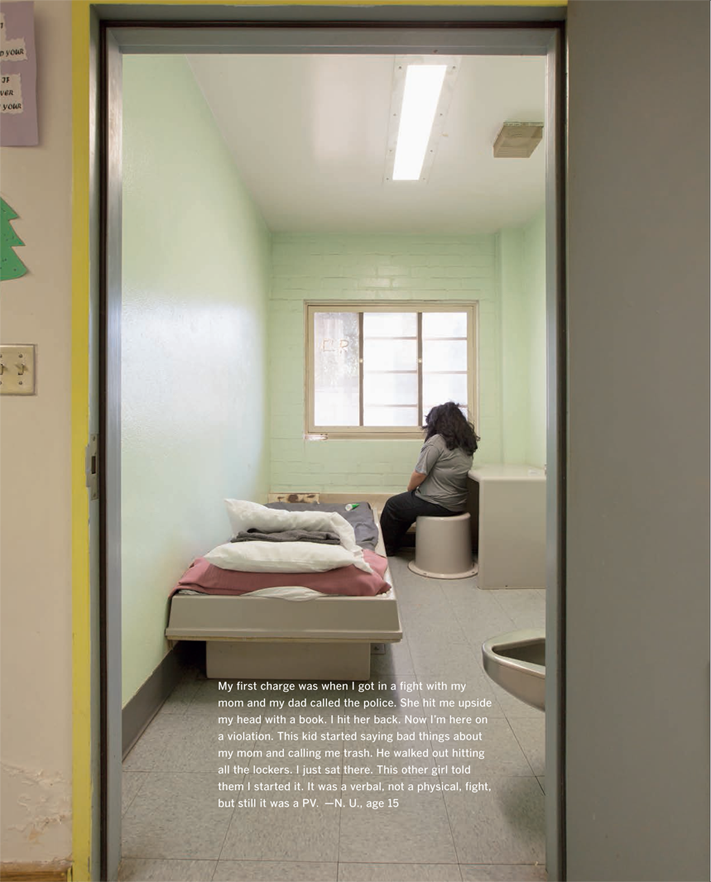

'I’m an ARY (at-risk youth). Mom thought I was at risk. I didn’t stay home. I hang out with my boyfriend and my best friends. But my mother blames everybody. She doesn’t like it that I’m rude and not going to school. My charges are truancy, not staying at home, and being rude. I’ve been here 14 times…For what I’ve done I don’t belong in a place like this, but I’m here.'

—C.J., age 16

I had nowhere else to go as far as DHS goes. I grew up in placement. My dad was doing drugs. My mom was doing drugs. They were both abusing me and my siblings. One time my mom put four of us in a dog cage and poured water on us. Another time my dad, a vet, put us in military duffel bags and left us in a basement for days. DHS took me into custody at 13. I was in every placement—foster homes, group homes, shelters, RTCs (residential treatment centers) I always ran away. Then I got arrested for beating up a staff at an RTC and had to go to detention…So I started getting violations for going AWOL. It was back and forth from locked up to placement. After I get out of here (an emergency shelter) I want to get an apartment with my fiancé.'

—B.T., age 18

'No one comes to visit me here. I only see my family in court.'

—E.Y., age 11

Leslie Acoca designed and created the Girls Health Screen© and is the Founder and Executive Director of the Girls Health & Justice Institute. Acoca lectures nationally and is a published author, producing presentations and publications for the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP), the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges (NCJFCJ), the Georgetown School of Law, Grantmakers in Health (GIH), the National Council on Crime and Delinquency (NCCD), the National Commission on Correctional Health Care (NCCHC), the California Department of Corrections, the Child Welfare League of America, and the Stoneleigh Foundation, The California Wellness Foundation, and the Casey Family and Kaiser Family Foundations.

Richard Ross is a photographer, researcher and professor of art based in Santa Barbara, California. Ross has been the recipient of grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Annie E. Casey Foundation, Fulbright, and the Center for Cultural Innovation. Ross was awarded the Guggenheim Fellowship in 2006 to complete work on Architecture of Authority, a critically acclaimed body thought-provoking and unsettling photographs of architectural spaces worldwide that exert power over the individuals confined within them. Ross’s Guggenheim support also helped launch an investigation of the world of juvenile corrections and the architecture encompassing it. This led to Ross’s most recent work, Juvenile In Justice, which turns a lens on the placement and treatment of American juveniles housed by law in facilities that treat, confine, punish, assist and, occasionally, harm them. A book and traveling exhibition of the work continue to see great success while Ross collaborates with juvenile justice stakeholders, using the images as a catalyst for change.

This piece was reprinted by EmpathyEducates with permission or license. We thank the Authors, Richard Ross, Marian Wright Edelman, Leslie Acoca, Dr. Karen Countryman-Roswurm, Mariame Kaba, Maisha T. Winn, for their kindness, scholarship, research, and for sharing what we believe is an invitation to question. We are honored and grateful for the opportunity to share what we believe we hope will spark a vital conversation…and is a visual masterpiece.