Project Description

The Selma Voting Rights Struggle: 15 Key Points from Bottom-Up History and Why It Matters Today

A shorter version of this article, “Ten Things You Should Know About Selma Before You See the Film,” is available on Common Dreams and the Huffington Post | With your help, we can bring this bottom-up history to the classroom.

Today, issues of racial equity and voting rights are front and center in the lives of young people. There is much they can learn from an accurate telling of the Selma (Dallas County) voting rights campaign and the larger Civil Rights Movement. We owe it to students on this anniversary to share the history that can help equip them to carry on the struggle today.

1. The Selma voting rights campaign started long before the modern Civil Rights Movement.

The Boyntons’ son Bruce Boynton, a Howard University law student, was the plaintiff in Boynton v. Virginia, a 1960 U.S. Supreme Court case that ruled segregated facilities serving interstate travel—such as bus and train stations—unconstitutional. This case helped inspire the freedom rides organized by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) in 1961.

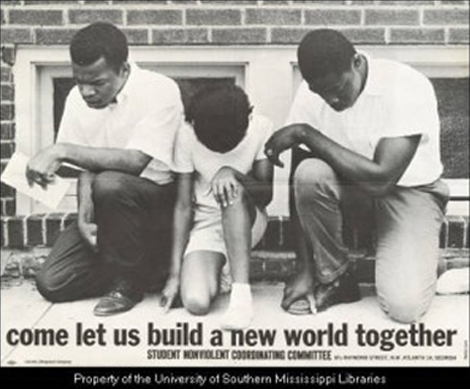

2. Selma was one of the communities where the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) began organizing in the early 1960s.

In 1963, seasoned activists Colia (Liddell) and Bernard Lafayette came to Selma as field staff for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), known as “Snick.” Founded by the young people who initiated the 1960 sit-in movement, SNCC had moved into Deep South, majority-black communities doing the dangerous work of organizing with local residents around voter registration.

Working with the Boyntons and other DCVL members, the Lafayettes held Citizenship School classes focused on the literacy test required for voter registration and canvassed door-to-door, encouraging African Americans to try to register to vote. (Learn more about the day-to-day work of SNCC in Selma from field reports by Colia and Bernard Lafayette. Here is an April 6, 1963, report by Colia Lafayette. Also read one by Bernard Lafayette in “Selma: Diary of a Freedom Fighter” by James Forman in The Making of Black Revolutionaries.)

Prathia Hall, a SNCC field secretary who came to Selma in the fall of 1963, explained:

'The 1965 Selma Movement could never have happened if SNCC hadn’t been there opening up Selma in 1962 and 1963. The later nationally known movement was the product of more than two years of very careful, very slow work.'

—Prathia Hall in Hands on the Freedom Plow (Read more of Hall’s account here.)

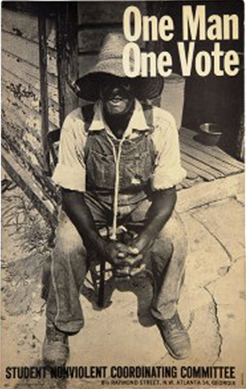

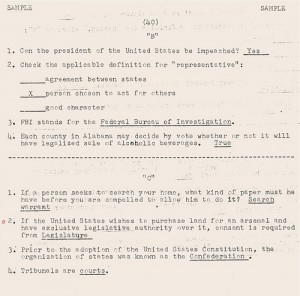

3. The white power structure used economic, “legal,” and extra-legal means, including violence, to prevent African Americans from accessing their constitutional right to vote.

According to a 1961 Civil Rights Commission report, only 130 of 15,115 eligible Dallas County Blacks were registered to vote. The situation was even worse in neighboring Wilcox and Lowndes counties. There were virtually no Blacks on the voting rolls in these rural counties that were roughly 80 percent Black. Ironically, in some Alabama counties, >a target=new href=http://www.teachingforchange.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/1960registeredvoters.pdf>more than 100% of the eligible white population was registered. See point #6 below for more examples.

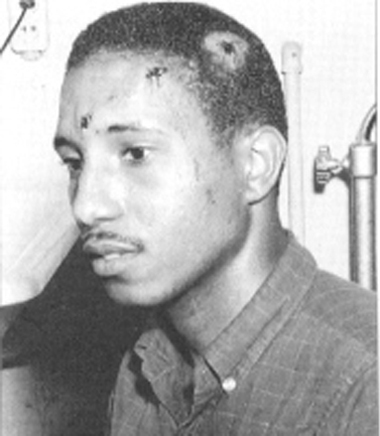

4. White terrorism created a climate of fear that impeded organizing efforts.

Alabama was extremely dangerous. For instance, in Gadsden, the police used cattle prods on the torn feet (of young protesters) and stuck the prods into the groins of boys. Selma was just brutal. Civil rights workers came into town under the cover of darkness.” —Prathia Hall.

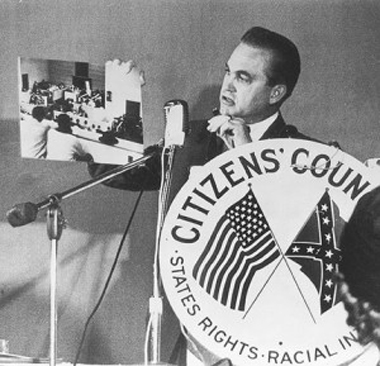

Alabama Governor George Wallace, holding photograph of “agitators” while speaking to Citizens’ Council group in Atlanta in 1963. Library of Congress.

To encourage attendance at a mass meeting, the Lafayettes combined a May 14, 1963, memorial service for Mr. Boynton with a voting workshop and rally. SNCC leader James Forman spoke and 350 people participated. Whites first tried to intimidate the minister into rescinding use of the church and then gathered in an armed, threatening crowd circling the church. Since the mob included Sheriff Jim Clark and other local lawmen, SNCC workers sought help (unsuccessfully) from federal officials and ultimately remained inside—singing freedom songs to bolster their courage—until 1 a.m. when the armed crowd had dispersed.

5. Though civil rights activists typically used nonviolent tactics in public demonstrations, at home and in their own communities they consistently used weapons to defend themselves.

Lafayette believed in the philosophy of nonviolence, but his life was probably saved by a neighbor who shot into the air to scare away the white attackers.

This practice of armed self-defense was woven into the movement and, because neither local nor federal law enforcement offered sufficient protection, it was essential for keeping nonviolent activists alive. (More in article by Charles E. Cobb Jr.)

6. Local, state, and federal institutions conspired and were complicit in preventing black voting.

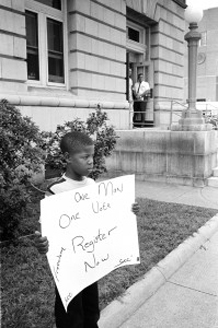

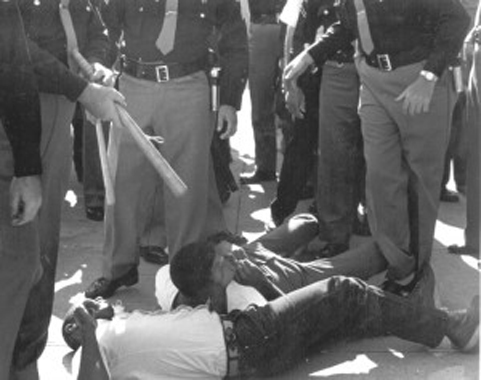

Photos: A brave young boy demonstrates for freedom in front of the Dallas County courthouse in Selma on July 8, 1964. Selma sheriff deputies approach and arrest him. Photos used by permission of Matt Herron/Take Stock Photo.

In another example, in summer 1964, Judge James Hare issued an injunction making it illegal for three or more people to congregate. This made demonstrations and voter registration work almost impossible while SNCC pursued the slow appeals process. Although the Justice Department was pursuing its own legal action to address discrimination against Black voters, its attorneys offered no protection and did nothing to intervene when local officials openly flaunted the 1957 Civil Rights Act.

The FBI was even worse. In addition to refusing to protect civil rights workers attacked in front of agents, the FBI spied on and tried to discredit movement activists. In 1964, the FBI sent King an anonymous and threatening note urging him to commit suicide and later smeared white activist Viola Liuzzo, who was murdered after coming from Detroit to participate in the Selma-to-Montgomery March.

7. SNCC developed creative tactics to highlight Black demand for the vote and the raw violence at the heart of Jim Crow.

To highlight African Americans’ desire to vote and encourage a sense of collective struggle, SNCC organized a Freedom Day on Monday, Oct. 7, 1963, one of the monthly registration days. They invited Black celebrities, like James Baldwin and Dick Gregory, so Blacks in Selma would know they weren’t alone.

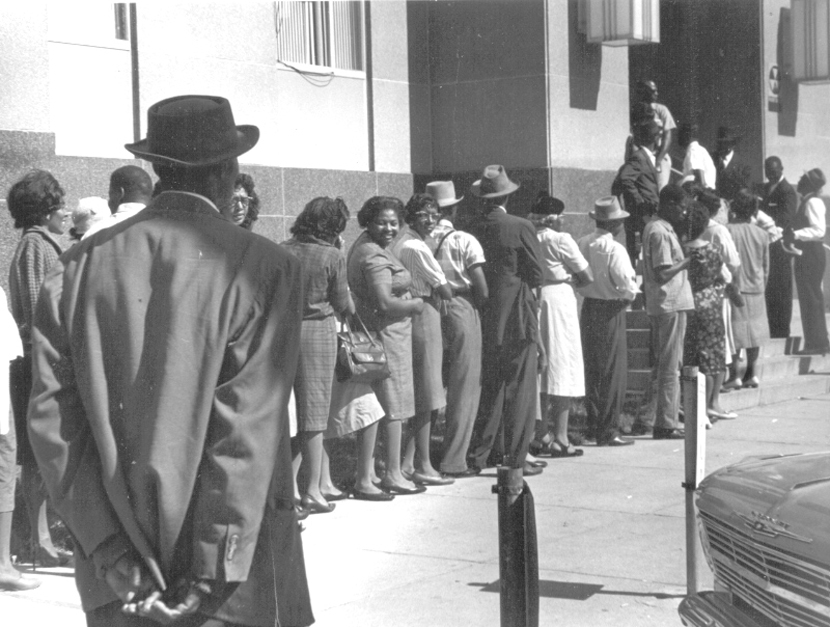

Over the course of the day, 350 African Americans stood in line to register, but the registrar processed only 40 applications and white lawmen refused to allow people to leave the line and return. Lawmen also arrested three SNCC workers who stood on federal property holding signs promoting voter registration.

By mid-afternoon SNCC was so concerned about those who had been standing all day in the bright sun, that two field secretaries loaded up their arms with water and sandwiches and approached the would-be voters.

Highway patrolmen immediately attacked and arrested the two men, while three FBI agents and two Justice Department attorneys refused to intervene. (Read an account of the day by Howard Zinn here.)

This federal inaction was typical, even though Southern white officials persistently and openly defied both the Civil Rights Act of 1957 and constitutional protections of free assembly and speech. The FBI insisted it had no authority to act because these were local police matters, but consistently ignored such constraints to arrest bank robbers and others violating federal law.

8. SNCC’s grassroots organizing around voter registration educated Justice Department attorneys about the need for additional voting rights legislation.

In Selma, as in parts of Mississippi, SNCC organizers played a key role in demonstrating the pervasive, unrelenting discrimination that prospective Black voters faced.

“Freedom Day” in Selma, October 1963. Blacks line up at the courthouse to apply to register to vote. © John Kouns.

This helped Justice Department officials (including John Doar and Burke Marshall) document discrimination in their own voting rights lawsuits filed against recalcitrant white registrars in the Deep South. Over time, the slow pace and piecemeal nature of these cases helped convince the Justice Department that a more systematic solution was necessary.

Doar, speaking at the 50th anniversary for the founding of the Civil Rights division at the Justice Department, asserted that “the Selma and voting rights success was built on the preceding but more obscure work of SNCC and the dirt farmers in Greenwood, Mississippi, which first prompted the department’s development of a comprehensive new approach to voting rights protection, that became the template for the department’s interventions in Selma.”

9. Selma activists invited Dr. King to join an active movement with a long history.

By late 1964, Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) were looking for a local community where they could launch a campaign to force the country to confront the Southern white power structure’s persistent and widespread discrimination against prospective Black voters.

Because SNCC and SCLC had different priorities in how they organized for change, SCLC’s entry into Selma created some tension between the two groups. SNCC used what activist Bob Moses calls “the community organizing” method, which was a slow, long-term approach focused on developing and supporting local leaders to demand access to full citizenship.

In contrast, SCLC sought to quickly mobilize large numbers of people for short-term demonstrations and goals. SCLC’s model relied on creating a crisis that would rally public opinion and force federal intervention. Read more about these differences here.

10. Youth and teachers played a significant role in the Selma Movement.

“I find it so strange now that people are writing stories just as if they were there from the beginning. The movement was on its final stages by the time they stepped out, yet they’ve taken all the credit. All the young people, like my classmate Cleophus Hobbs, have been written out of the Selma Movement.'

— Bettie Mae Fikes in Hands on the Freedom Plow

In Selma, the “teachers’ march” was particularly important to the young activists at the heart of the Selma movement. One of them, Sheyann Webb, was just 8 and a regular participant in the marches. She reflects,

'What impressed me most about the day that the teachers marched was just the idea of them being there. Prior to their marching, I used to have to go to school and it was like a report, you know. They were just as afraid as my parents were, because they could lose their jobs. It was amazing to see how many teachers participated. They follow(ed) us that day. It was just a thrill.'

Sheyann Webb, in Voices of Freedom

Though the top-down approach to the Civil Rights Movement focuses on King, presidents, and the Supreme Court, at the grassroots level, the Movement was dominated by young people, women, and others with limited formal education and scarce economic resources.

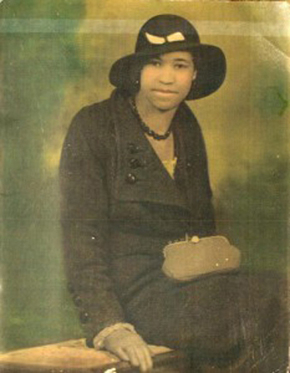

11. Women were central to the movement, but they were sometimes pushed to the side and today their contributions are often overlooked.

Marie Foster was another significant local activist, teaching Citizenship classes even before SNCC arrived and remaining steadfast through the slow, brutal work of building a movement in the context of extreme repression. In early 1965 when SCLC began escalating the confrontation in Selma, Mrs. Boynton and Foster were both in the thick of things, inspiring others and putting their own bodies on the line. They were leaders on Bloody Sunday and the subsequent march to Montgomery. Whether working behind the scenes when the movement was just a handful of people or near the front of the line when the entire nation was watching Selma, they were courageous and unwavering.

Though Colia Liddell Lafayette worked side by side with her husband Bernard, recruiting student workers and doing the painstaking work of building a grassroots movement in Selma, she has become almost invisible and typically mentioned only in passing, as his wife.

Her father and grandfather worked with the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union and she was a strong organizer in her own right, founding an important NAACP Youth Branch in Jackson, Mississippi, and working for Medgar Evers before moving to Selma to organize with her new husband. She remained there until, at the request of SNCC Executive Secretary James Forman, she relocated to nearby Birmingham to help organize the spring 1963 demonstrations. In Birmingham, being pregnant offered no protection and she was badly injured when white officials used fire hoses to attack demonstrators.

Prathia Hall, a Philadelphia native who began working with SNCC in Southwest Georgia, joined the Selma effort in the fall of 1963 when the Lafayettes moved on to Nashville. Philosophically nonviolent, she was a brilliant organizer and orator who later became an ordained minister. She returned to Selma after Bloody Sunday to help SNCC and local activists figure out how to move forward.

Diane Nash, whose plan for a nonviolent war on Montgomery inspired the initial Selma march, was already a seasoned veteran, leading the Nashville sit-ins, helping found SNCC, and taking decisive action to carry the freedom rides forward. In 1961 she married Jim Bevel and then followed him out of SNCC and into SCLC. According to SCLC insider Andrew Young, “No small measure of what we saw as Jim’s brilliance was due to Diane’s rational thinking and influence.”

Young women singing freedom songs in a Selma church, 7/8/1964. (c) Matt Herron/Take Stock Photos.

These are just a few of the many women who were critical to the movement’s success—in Selma and across the country. Like their male co-workers, they organized, demonstrated, taught, preached, and strategized. They also cooked and housed workers, tried to register, and recruited friends and neighbors. And, like men, they were threatened, attacked, beaten, and fired. Through it all they stood up for themselves and their communities, insisting on their “freedom rights.”

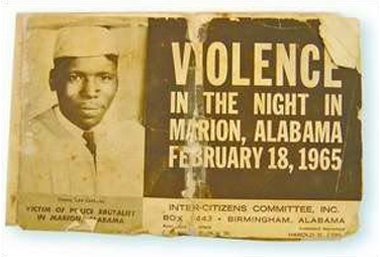

12. The Selma march was triggered by official white terrorism.

The idea originated with a proposal for action that SNCC founder and SCLC staffer Diane Nash wrote (with her then husband SCLC staffer Jim Bevel) after the Birmingham church bombing. Nash had suggested an all-out nonviolent campaign targeting Alabama’s capitol, Montgomery.

13. Although the mass violence of Bloody Sunday generated national outrage, the majority of whites still did not understand how deeply embedded racism is in our country’s institutions.

Although the Selma march drew national attention to black disfranchisement and white violence, long before Bloody Sunday, President Lyndon Johnson, the Justice Department, and members of Congress knew African Americans were being denied voting rights. The nation responded less to this outrage than to the public violence inflicted by out-of-control lawmen and later to the presence of white people of goodwill, including celebrities, who came from across the country at King’s invitation.

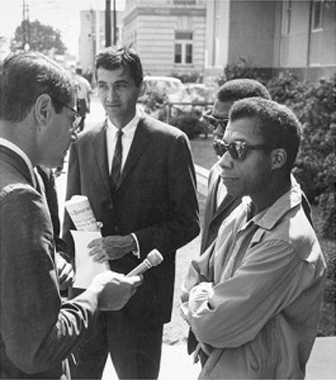

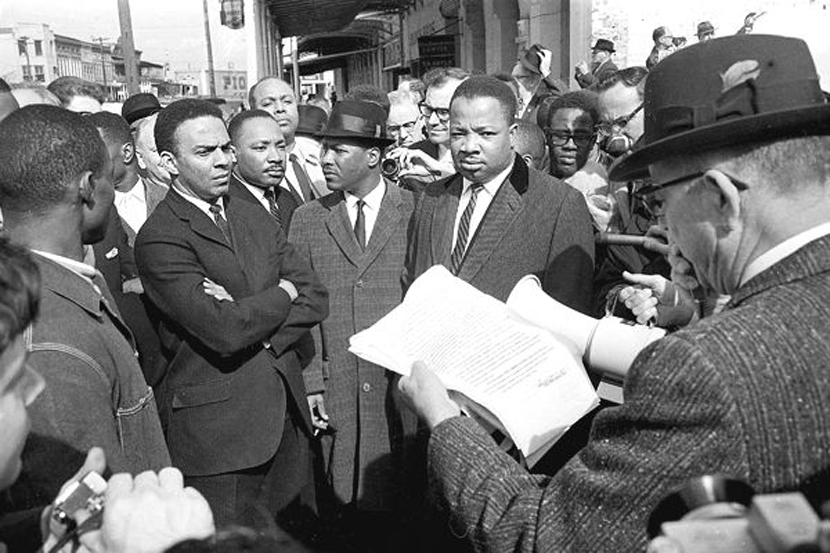

At the Edmund Pettus Bridge on March 9, 1965, a federal marshal reads an injunction to Andrew Young (arms crossed), Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and other marchers. AP Photo.

This set up what became known as Turnaround Tuesday. After King invited people to come join another march, Federal District Judge Frank Johnson issued a temporary injunction blocking the march and Lyndon Johnson convinced King to observe it. Rather than admit this publicly, King led the march to the bridge, then prayed and turned back, much to the chagrin of SNCC workers and many who had come to join and bear witness.

When Rev. James Reeb, one of those who answered King’s call, was subsequently murdered by white thugs on the streets of Selma, his death was noted by President Johnson in his famous “We Shall Overcome” speech calling for the legislation that became the Voting Rights Act. There was considerably more national outcry over Reeb’s death, than Jimmie Lee Jackson’s a couple weeks earlier. (Rita Schwerner Bender addressed this in relation to the murder of her then husband Mickey Schwerner and two other civil rights workers at the beginning of the 1964 Freedom Summer project in Mississippi.) Charles Payne’s “Rough Draft of History” is an excellent analysis of how media coverage of the Civil Rights Movement perpetuated a top-down, normative understanding of the issues. Hasan Kwame Jeffries’ essay on cartoons from Barack Obama’s first campaign for president shows how these normative understandings of the Movement continue today.

14. Though President Lyndon Johnson is typically credited with passage of the Voting Rights Act, the movement forced the issue and made it happen.

The Selma Campaign is considered a major success for the Civil Rights Movement, largely because it was an immediate catalyst for the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson on Aug. 6, 1965, the Voting Rights Act guaranteed active federal protection of Southern African Americans’ right to vote.

Although Johnson did support the Voting Rights Act, the critical push for the legislation came from the Movement itself. SNCC’s community organizing of rural African Americans, especially in Mississippi, made it increasingly difficult for the country to ignore the pervasive, violent, and official white opposition to Black voting and African American demands for full citizenship. This, in conjunction with the demonstrations organized by SCLC, generated public support for voting rights legislation. Scholar Charles Payne warns us that it is easy to focus on major legislation when, in fact, what may be more significant is the groundswell that made it necessary or subsequent action that made it meaningful.

15. The Voting Rights Act was not an end to the movement.

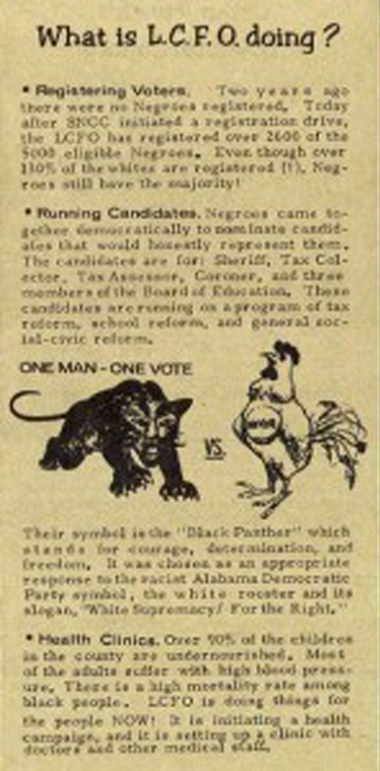

SNCC worked with local African Americans under the premise that voting was, to quote SNCC’s Courtland Cox, “necessary but not sufficient.” Cox’s rhetorical question, “What would it profit a man (person) to gain the vote and not be able to control it?,” guided SNCC’s approach to working with local African Americans to organize the independent Lowndes County Freedom Party (LCFP).

Together they organized the LCFP, known for its Black Panther emblem, and for a brief period, practiced what historian Hasan Kwame Jeffries calls “freedom politics.” Although Black access to the vote was not a panacea, its significance became tangible when movement activist John Hulett was elected sheriff and immediately eliminated the police brutality that had plagued the community since the end of Reconstruction.

Lessons for Today

This brief introduction to Selma’s bottom up history can help students and others learn valuable lessons for today. As SNCC veteran and filmmaker Judy Richardson said,

If we don’t learn that it was people just like us—our mothers, our uncles, our classmates, our clergy—who made and sustained the modern Civil Rights Movement, then we won’t know we can do it again. And then the other side wins—even before we ever begin the fight.

Federal protection for voting rights is still necessary.

In July 2013, the deeply divided United States Supreme Court gutted the Voting Rights Act in Shelby v. Holder, a case coming out of Alabama. Arguing in part that it is arbitrary and no longer necessary to focus exclusively on the former Confederacy, the court’s majority eliminated the pre-clearance requirement for nine Southern states. This means that the Justice Department is no longer responsible for (or allowed to) check new laws for racial bias. Given widespread efforts to block voting access, it may well be arbitrary to hold the former Confederate states to a different standard. But the response of those states—along with other forms of voter suppression throughout the country—makes it crystal clear that we still need robust, proactive tools to protect voting rights for all citizens, but particularly African Americans and others who are still targeted. Rather than being curtailed, the Voting Rights Act should be extended. No doubt future historians will look back at today’s voter ID laws and other forms of voter suppression (including Jim Crow voting booths) as a 21st-century version of the literacy tests, poll tax, and grandfather clause of the 20th century.

The Civil Rights Movement made important gains, but the struggle continues.

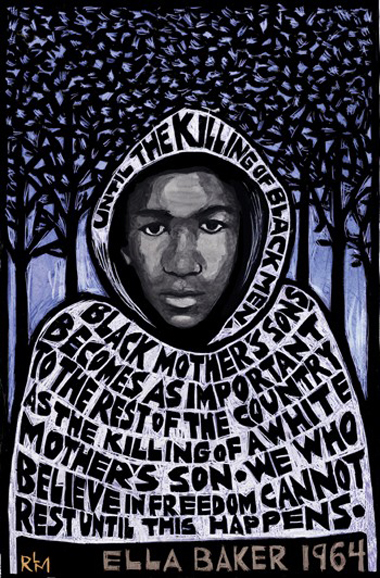

In 1964 she asserted, “until the killing of black men, black mother’s sons, becomes as important to the rest of the country as the killing of a white mother’s son, we who believe in freedom cannot rest.” Baker’s words were captured in “Ella’s Song,” by Bernice Johnson Reagon, a SNCC field secretary and founder of Sweet Honey in the Rock. Although the context has changed, there are many direct links between the freedom struggle of the 1950s and 1960s and today’s issues. And millennial activists are creating a new movement that builds on the work of previous generations.

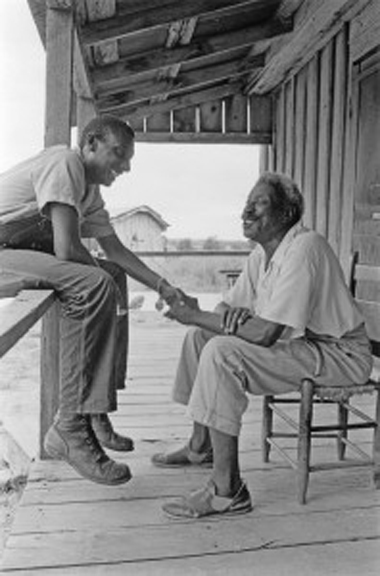

SNCC’s voter registration campaigns offer an important model for effective community organizing today.

Profoundly influenced by Ella Baker, SNCC workers put their bodies on the line to demand desegregation, refused to back down in the face of violence, and joined hands to work alongside an older generation, organizing around voter registration and community empowerment. Working with and learning from people who had long been marginalized, SNCC helped develop and support new leadership while challenging our country to move closer to its democratic ideals.

© Teaching for Change 2015

References and Suggested Resources

Credits

Emilye Crosby is a professor of history and coordinator of Black Studies at SUNY Geneseo. She is author of A Little Taste of Freedom (University of North Carolina Press, 2005) and editor of Civil Rights History from the Ground Up (University of Georgia Press, 2011). She is currently a fellow at the National Humanities Center where she is working on a history of women and gender in SNCC.

Deborah Menkart collaborated on the development of the list of 15 points, editing, and layout. Liz Dierenfield provided extensive research. Valuable feedback was provided by Sarah C. Campbell, Kathleen Connelly, Julian Hipkins III, Wesley Hogan, Hasan Kwame Jeffries, and more.

Permission to reprint photos and text was generously provided by Matt Herron/Take Stock Photos, Holly Jansen, Charles M. Payne (author of I’ve Got the Light of Freedom), and the Howard Zinn Trust. The Lowndes County photos credited to the Library of Congress are from the Prints and Photographs Division, LOOK Magazine Collection, LC Look-Job 65-2434.

This piece was reprinted by EmpathyEducates with permission or license. We thank | Originally Published at Teaching for Change and Emilye Crosby for their kindness, research and reflections. We are grateful for the lessons history teaches. May we never forget and keep moving. The struggle continues.