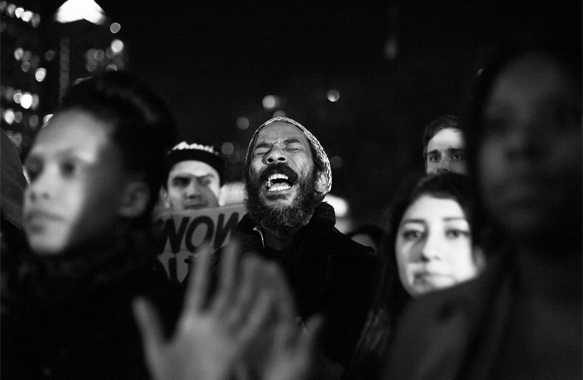

Flickr image cc by Phil Roeder

By John O’connor | Originally Published at Florida State Impact, National Public Radio. February 10, 2014 7:54 AM

Chris Guerrieri is a Jacksonville art teacher who also blogs about education.

Last month he sent us an email about Florida’s Common Core standards.

“My question was: How does Common Core affect poverty?” he asked.

More than half of all Florida students qualify for the federal free and reduced-price lunch program.

It’s a short-hand way to gauge poverty. Florida’s rate is about one-sixth higher than the national average.

We took Guerrieri’s question to Paul Thomas. He’s a professor at South Carolina’s Furman University and has written a book about the effects of poverty on education.

“If you’re an African-American male student,” he said, “you are disproportionately likely to be excluded from advanced classes and you’re also likely to sit in classrooms with teachers that have no experience and possibly no certification. There’s absolutely nothing in Common Core that addresses any of those inequities.”

Besides, he said there’s no evidence schools have a problem with standards.

Studies by the National Education Policy Center and the Brookings Institution predict the new standards won’t improve academic achievement.

But educators who have seen Common Core at work disagree.

Florida is one of 45 states to fully adopt the standards.

Baltimore City schools are a few years ahead of Florida in using Common Core.

Sonja Brookins Santelises was Baltimore’s academic chief before recently moving to D.C.-based advocacy group The Education Trust.

She said Common Core charts a clearer course for educators on how to get elementary school students ready for college – something that wasn’t happening before.

“The standards that we were setting across the country,” she said, “were very, very different depending on, unfortunately still, the ZIP code and the race and the ethnicity of the young people in question. And I think what Common Core does is really open up the black box. So what does the trajectory look like?”

Also, Brookins Santelises said poor students are more likely to switch schools during the year. Common Core should mean those students are more likely to pick up where they left off.

The new standards ask more of students. By the time Brookins Santelises left the Baltimore district, schools were improving.

And before Baltimore, she worked in Massachusetts – the state whose standards are a model for Common Core. The Bay State is now one of the top-ranked education systems in the country.

Common standards will allow districts across the U.S. to share tips, techniques and lessons that work best for low-income or minority students.

In Florida, Common Core is already in place through second grade. At Sallye B. Mathis Elementary in Jacksonville, Principal Angela Maxey saw a difference too.

“So now we do not have, as an educator, an excuse for not educating all children the same way,” she said. “So I believe in this type of instruction.”

Florida is still using test results to measure student performance, grade schools and calculate teacher pay. And that’s why Common Core critics like Chris Guerrieri doubt anything will change. He thinks test scores will be the focus – not poverty or social policies.

“And as long as we keep ignoring poverty that’s all we’re going to do,” Guerrieri said. “It’s just going to be a cycle of the next new thing. It’s new and not necessarily better.”

But if Common Core does improve U.S. schools, nearly everyone agrees a better education is the best long-term solution for poverty.

StateImpact is answering reader-submitted questions about the Common Core, a new set of expectations for what students should know and be able to do in math and English at each grade level. Florida is one of 45 states that have fully adopted the Common Core.

Got a question about Florida’s move to the Common Core? We’re here to help. Reach out to us on Twitter, Facebook or emali and submit your question.

Leave A Comment