Project Description

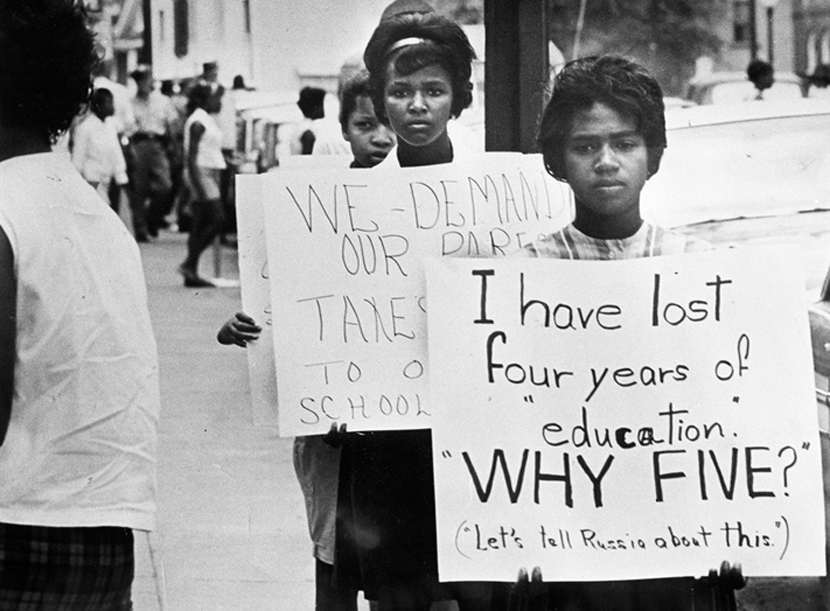

One county in Virginia froze its black citizens out of public education -- for five long years.

Excerpt: Southern Stalemate: Five Years without Public Education in Prince Edward County, Virginia

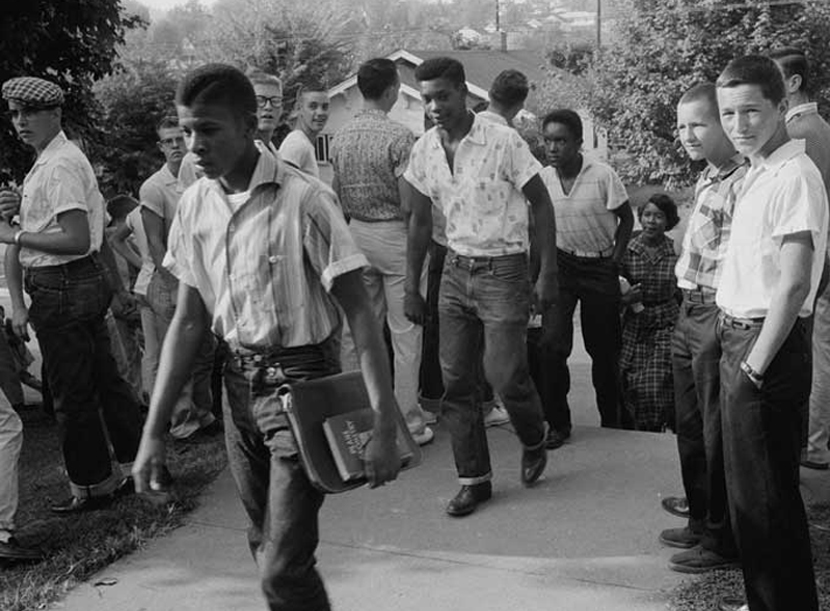

Prince Edward County, Virginia, is the neglected chapter in American civil rights history. In 1951, black high school students in this rural county of 14,000 went on strike to protest unequal school facilities, several years before civil rights activities elsewhere in the South began to penetrate public consciousness. The strike led to an NAACP lawsuit that became one of five cases decided by the Supreme Court in 1954’s Brown v. Board of Education, which outlawed official segregation in public schools.

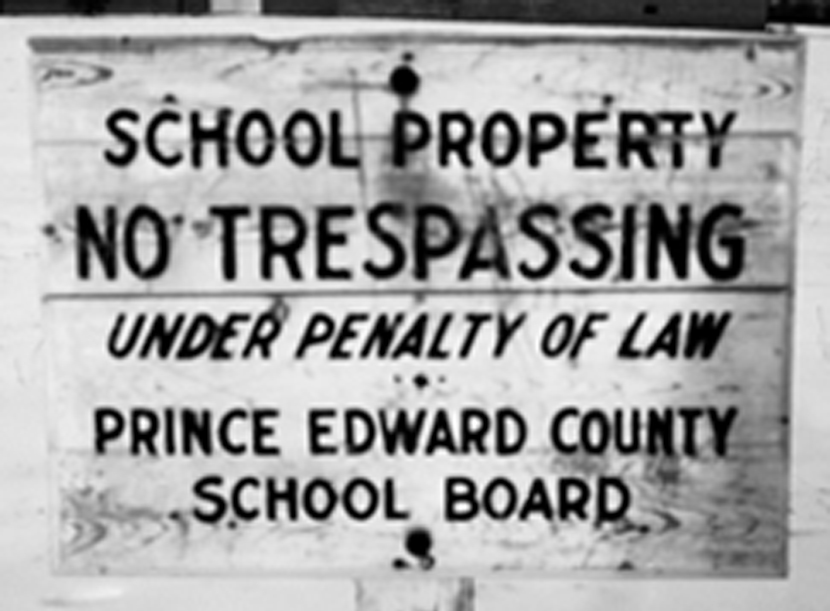

Faced with a federal court order to desegregate its schools in fall 1959, the county withdrew from the public school business for five years, reopening schools in 1964 under orders from the Supreme Court. Nearly 2,700 black students were locked out of public schools; fewer than 500 received some formal education outside the county. During the closing years, most white students enrolled in the segregated Prince Edward Academy. White county leaders believed that they were creating a blueprint for defying desegregation mandates in the rural South and, they hoped, throughout much of the United States. Had the Supreme Court decided not to strike down the school-closing strategy—13 years after the school strike, a decade after Brown and five years after schools had closed—these Virginia segregationists may have been proven correct.

Educational Options for Blacks

The first I heard (about the closings) was from (my classmates(. Some of the other kids were saying that schools were going to be closed and, of course, I didn’t believe it and a lot of us didn’t believe it, until it actually was…But I lived right behind one of the schools that I went to, the elementary school, and that school was chained, the doors was chained, so I knew then (laughs)—that was a wide awakening right there.

Adults, too, were caught off-guard by the closings. Vanessa Venable, who was teaching in PEC’s black schools in 1959, described Farmville in the 1950s as “a very pleasant place, a very congenial place with apparently no discord anywhere. Everything was moving very smoothly.” The school closings tore away those assumptions: “We were all very, very upset. We didn’t think that we were living among people who would be that mean. We expected something but not that drastic a move. We thought that the white people in Farmville were all friendly neighbors. But when this happened we began to wonder whether we were living among neighbors or whether we were living among enemies.”

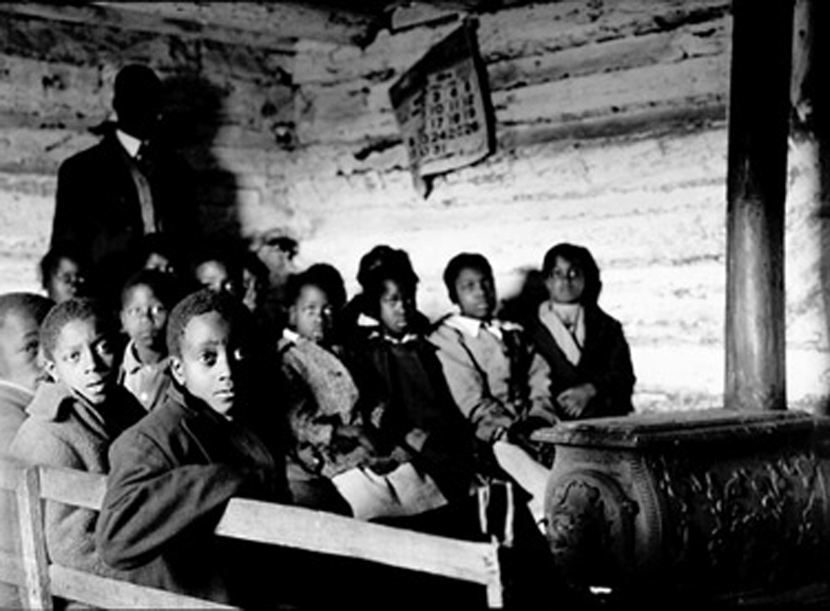

Even before the schools closed, Negro children found themselves in an isolated, rural locale that offered them no “access to a movie

The deep pain and loss of faith in the white people of this area by the Negro community is a very difficult condition to explain vividly. Apparently for many decades there has been a residual trust among the members of the Negro community in the good faith and sincere interest of the white people in the health and welfare of the total population of the County. The extremity of the statements made through the past several years by many of the leading citizens of the white community indicating their attitudes toward the general Negro citizen served to undermine this residual good will.

While Boyte may have overestimated the reservoir of good will that previously existed between blacks and whites, the school closings dissolved any trust that remained.

In December 1959, the Herald ran a front-page story on Southside Schools, a public corporation chartered by some of the county’s most zealous segregationists to help local Negroes form their own private schools. The whites behind Southside Schools did not consult black community leaders before making their announcement. Board members asserted that “the formation of this corporation was delayed because it was our opinion that responsible Negro citizens of the county should provide the Fleadership. There has been no action along this line, however.” Hinting inadvertently at one source of black skepticism, Wall noted in private correspondence that Southside Schools “has met with approval, even from ardent segregationists, both here and in Virginia and other states.” The Herald publisher had acknowledged privately in September that “there is no hope that the Negroes would be interested in private schools even as a stopgap.” Wall was right: only one black family submitted an application to Southside Schools, despite a promise that state tuition grants would cover the cost of tuition.

The white leaders behind Southside Schools “will never concede that the colored race has changed. No longer do we let others decide what we need, or choose our leaders, or direct our thinking, because we can do it ourselves.” Beyond the questionable motives behind the scheme, Griffin pointed to the lack of black teachers in the county—nearly all had left to continue teaching elsewhere—and the fact that most black ministers favored integration and would be unwilling to let their churches be used for segregated schools.[/fusion_builder_column_inner]

Moreover, county blacks did not have substantial financial resources, and did not have a clear picture of what monetary contributions, if any, whites would be willing to make, or what they might ask in return. Dropping the lawsuit was the likely quid pro quo. A black farmer appraised the private-school proposal succinctly: “Why should I follow men that don’t acknowledge Almighty God and the Supreme Court?”

Southside Schools president Roy B. Hargrove admitted that the group of whites formed the corporation: “

Four of the 10 individuals who sought the Southside Schools charter were active in the foundation; J.B. Wall Jr., served as vice-president of Southside Schools, and attorney for both organizations. If blacks were in private schools, the stench of callousness inherent in the closure of public schools might drift away. In addition, tuition for students at the black private school would be financed by state tuition grants, which the academy was not accepting for fear of legal repercussions.

In March 1960, local contractor C.W. “Rat” Glenn—a member of the PESF’s Executive Committee widely known as someone who would resort to violence and intimidation to maintain segregation—reported that the foundation might be wise to only accept local grants in the coming school year. “However,” he added, “should the negroes come up with a good private school and apply for State Tuition Grants it would change our thinking along this line right much.” That summer, local segregationist Robert Taylor requested that the school board rent First Rock School, a Negro elementary school, so that he could open a Negro private school. Nothing came of the request. Henry Powell, a black teacher and farmer, was offered $1,500 by a conservative black man who wished to use Powell’s farm to operate a black school.

Though this was a large sum of money at the time—and he could have used it—Powell turned the man down because “he was an Uncle Tom…and I thought about how could I justify cooperating with this…guy to my friends. How could I tell Reverend Johns?” (the firebrand preacher whose niece headed the 1951 student strike). Virginia NAACP executive secretary Lester Banks stressed the importance of dramatizing the denial of education: “Had there been any wide acceptance of private schools, it would have had a disastrous effect on other Negro centers, in the Black Belt and elsewhere in the South. Even if the case was still prosecuted, the effect would have been disastrous.”

[/fusion_builder_row_inner]Christopher Bonastia is associate professor of sociology at Lehman College and the City University of New York Graduate Center, as well as associate director of the Lehman Scholars Program and Macaulay Honors College at Lehman. He is the author of Knocking on the Door: The Federal Government’s Attempt to Desegregate the Suburbs.

Reprinted with permission from Southern Stalemate: Five Years without Public Education in Prince Edward County, Virginia, by Christopher Bonastia, published by the University of Chicago Press. Copyright 2012 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved.

This piece was reprinted by EmpathyEducates with permission or license. We thank the Author, Professor Bonastia for his kindness, observations, research and what we believe is a vital reflection.