Columbia University’s Teachers College held two Masters convocations on May 21. During the ceremonies students held up signs that read “I am not a number” and “not a test score.” Photo by George Joseph<

By George Joseph. Originally Published at In These Times. June 13, 2013

Columbia University’s Teachers College, long esteemed as a premier institution for progressive pedagogy, is having an identity crisis. While majestic quotes from education philosopher John Dewey remain etched across the walls of the school’s Morningside Heights headquarters, his words ring increasingly hollow as Teachers College President Susan Fuhrman continues to serve on the board of—and hold 12,927 shares in—Pearson, the world’s largest educational resource corporation, which distributes everything from standardized tests and textbooks to teacher certification and curriculum programs. Arguing that this role hampers their ability to speak out against the disastrous policy of high-stakes testing, students at Teachers College began a campaign last month demanding that Fuhrman divest from Pearson.

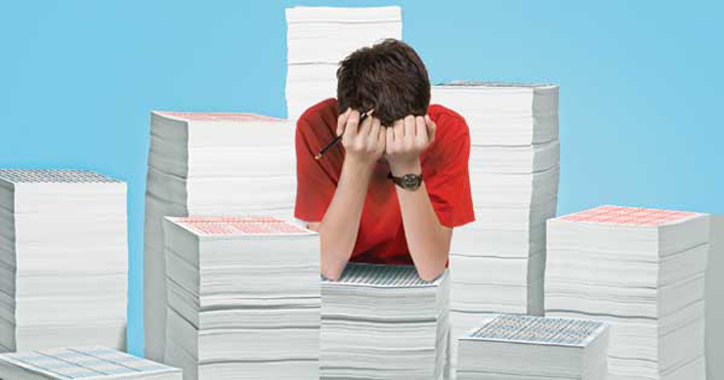

Over the past few years, Pearson has risen from a small British publishing firm to an “education resource” giant, raking in the profits that come with the increasing privatization of the American education system. Pearson’s involvement in shaping education in New York state is a prime example. In 2010, when the state, long known as a beacon for its strong curriculum standards, was formulating its new standardized “Common Core” program, lawmakers handed Pearson a generous five-year, $32 million contract to administer tests, in addition to another $1 million for helping the state Education Department with testing services. Having seized control of standardized testing in states like New York, Pearson has also made its own costly textbooks essential for teachers under pressure to turn out high-test scores, thereby turning additional profits while transforming classrooms into Pearson test-prep centers.

To many Teachers College students, Fuhrman’s association with Pearson places her at odds with the school’s reputation as one of the strongholds of “critical pedagogy,” an educational philosophy that empowers students to realize their freedom and combat diverse forms of power. Pearson’s model, mandating that students spend weeks of class filling out hundreds of Scantron bubbles, doesn’t exactly jibe with Teachers College’s vision for educational empowerment.

Many students also feel stung by Fuhrman’s Pearson connection in light of the state’s recent decision to adopt Pearson’s Teacher Performance Assessment, which will require teacher trainees to send two 10-minute videos of themselves teaching to Pearson offices and fill out a Pearson-approved take-home test in order to be considered for certification—and pay Pearson a $300 fee. As Daiyu Suzuki, a fifth year doctoral student, put it, “Quality teaching, which must be shaped around the unique circumstances of its students, cannot be evaluated on the basis of Pearson’s one-size-fits-all testing rubric.”

In response, the students of Teachers College have closed their books and taken matters into their own hands. On May 9, more than 50 students packed the hallway outside the faculty vote on Fuhrman’s proposed annual budget, holding up signs decrying Fuhrman’s ties to Pearson and the creeping corporatization of education. Encouraged by their presence, the faculty voted down the administration’s austere proposal, eliciting a 10-minute round of applause as professors triumphantly filed out, high-fiving students and thanking them for their support.

After this strong initial showing, students began meeting regularly to organize. United with faculty members, students have a wide list of concerns, ranging from the disconnect between executive administrators’ bonuses—reportedly totaling $315,000—and the weakening financial support for doctoral and master’s students, to President Fuhrman’s corporate connections. At the school’s May 21 commencement, hundreds of students in caps and gowns held up signs reading, “I am not a number” and “not a test score,” directly in the view of Merryl Tisch, New York’s Chancellor of the Board of Regents, who was being awarded the Medal for Distinguished Service. As the head of New York State’s education system, Tisch was instrumental in Pearson receiving its $32 million contract.

Perhaps the most grievous consequence of Fuhrman’s tenure at Teachers College is an emerging cynicism within the student body, threatening the school’s very capability to train and turn out inspirational teachers. As Diane Ravitch, former U.S. Assistant Secretary of Education, wrote in an email:

Testing is big business these days. Educators must be free to criticize the tests and their publishers. Faculty members at

[Teachers College] might feel constrained by the fact that the president of the institution is on the board of Pearson, my own sense is that she has a conflict of interest, because as a board member she is not [in] a position of independence to speak out against the misuse and overuse of testing and how it hurts children and warps education.Many students say they have growing doubts that teaching could ever live up to the ideals they eagerly studied in the classroom. Diana Rodriquez-Gomez, a doctoral student, says that Fuhrman’s very position led her to question her decision to become a teacher:

It’s funny because we read so much about [Paulo] Freire and Dewey, then when we come to school, it’s like ‘Are you kidding me?’…For me it’s an ethical matter; she’s sitting at two tables that accomplish completely different things. A university produces critical knowledge. Pearson promotes the privatization of education. When you’re a teacher, and you see what standard exams do, you don’t know if you want to keep doing that!

Fuhrman was unavailable for an interview, but on May 15 she released a statement arguing her ties to Pearson could only help facilitate better discourse:

I realize that my affiliation with the board of Pearson is disturbing to various members of the TC community…However, I believe strongly that the best way to represent those views is to be fully engaged in—and, I would hope, influence—the discussion of the role of the private sector in public education.

But as students made clear in their response it is the discussion itself—the corporate narrative that has for so long vilified teachers, heralded high stakes testing, and promoted the privatization of the public school system—that must be challenged. As Suzuki argues: “We, as a student group, find it ironic that she repeatedly uses the dominant discourse as excuses to justify the unjust practices of TC, whereas we are saying it’s that same dominant discourse that we need to disrupt and change.”

John Dewey once wrote, “As long as politics is the shadow cast on society by big business, the attenuation of the shadow will not change the substance.” Perhaps President Fuhrman needs a little refresher course.

ABOUT THIS AUTHOR

George Joseph is a reporter, focusing on education and labor issues in New York City. He is also an undergraduate, concentrating in Education and Sociology, at Columbia University, where he organizes with the activist group Student Worker Solidarity.

Leave A Comment