By Valerie Strauss | Originally Published at The Washington Post. August 2, 2013

Increasingly we hear that academic work, including test prep, is reaching down into the lowest grades, even preschool. Here’s a post with teacher concerns on the issue, written by Geralyn Bywater McLaughlin, Nancy Carlsson-Paige, and Diane E. Levin. They run the nonprofit called Defending the Early Years, which seeks to rally educators to take action on policies that affect the education of young children. DEY is a non-profit project of the Survival Education Fund, a 501(c)(3) tax-exempt educational organization based in Watertown, Massachusetts. You can read more stories from teachers at the DEY website, on the “Voices from the Field” page.

By Geralyn Bywater McLaughlin, Nancy Carlsson-Paige, and Diane E. Levin

“We spend the majority of the day testing one way or another.” ~ A second grade public school teacher from North Carolina

A disturbing shift is underway in early childhood classrooms around the country. Many classrooms, especially those that depend on public funds, look more and more like classrooms for older children where standards, testing, and accountability rule. Federal and state mandates are pushing academic skills and testing down to younger children, even preschoolers. These days, there is less and less emphasis on promoting child development, active, play-based learning, and hands-on exploration for our nation’s youngest learners.

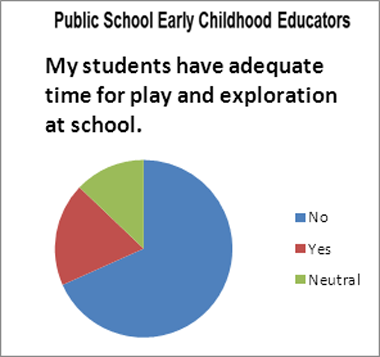

At our nonprofit project, Defending the Early Years (DEY), we launched an online survey to find out what teachers think about how current education mandates are affecting their classrooms, their teaching, and children’s learning. Over the course of the 2012-2013 school year, 185 early childhood classroom teachers (Pre-K – 3rd Grade) from across 31 states voluntarily came to our website to document their experiences. Overwhelmingly, these teachers reported that recent policy changes have hindered — not helped — their young students. Although they don’t represent a randomly selected group, these teachers are from a variety of early childhood settings including public and private schools, Head Start classrooms, and center-based preschools who took their own time to share their experiences and stories with DEY. A large majority of the teachers completing this survey say that playful learning is disappearing from their classrooms, and that developmentally inappropriate activities and assessments are now at the forefront of daily classroom life. Teachers in public schools expressed the most concern.

Furthermore, what is learned through play provides an essential foundation for later academic learning. Early childhood teachers are trained to promote the optimal development and learning of young children through play.

And according to this survey, half of teachers — and more than two-thirds of those in public schools — feel they are now unable to do so. Many teachers in the survey commented about their struggles to keep play at the center of the curriculum, despite the pressure they feel to teach specific skills and adhere to scripted curricula. A public school kindergarten teacher from Maine wrote:

When teachers in my district bring this

[need for play] to the attention of administrators for discussion, we ‘get our hands slapped’. After thirty-plus years of teaching, I am currently working at least twelve-hour days in an attempt to plan in such a way that I can provide time for my students to have opportunities for play and exploration as well as the lessons I am mandated to teach. Every day staff members comment on how they can’t do this much longer, as it goes against every belief we have in teaching young children.Another item on the survey asked teachers about the developmental appropriateness of what they are expected to teach. In response to the statement, “I am required to engage in teaching activities that are not developmentally appropriate for my students,” 60 percent of all teachers agreed. Again, the public school teachers agreed in greater numbers — 85 percent said that they are required to teach activities that are not developmentally appropriate for their students.A New York public school kindergarten teacher with over 15 years of experience explained:

Kindergarten students are being forced to write words, sentences, and paragraphs before having a grasp of oral language…We are assessing them WEEKLY on how many sight words, letter sounds, and letter names they can identify. And we’re assessing the ‘neediest’ students’ reading every other day.

When the teaching is not developmentally appropriate, children suffer academically and emotionally. As one teacher described:

Our district has seen a large increase in serious negative behaviors; yet do not want to look at the correlation between this and our increased expectations. Instead, we suspend five and six year olds.

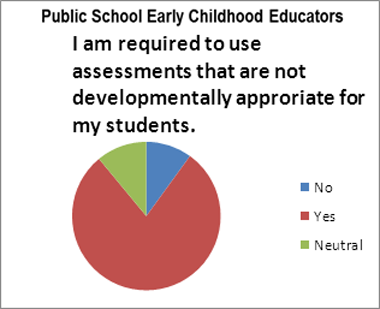

Finally, we asked teachers to respond to the following statement: “I am required to use assessments that are not developmentally appropriate for my students.”Fifty three percent of the teachers agreed with this statement. And in keeping with the trends already seen, 79 percent of public school teachers agreed that they are required to use assessments that are not developmentally appropriate for their students. A public school first grade teacher from North Carolina gave this example:

Now that we use the Common Core Standards, I had to assess my first graders on missing addends when they could barely do regular addition problems – in the first few weeks of school. Totally inappropriate.

Another teacher from North Carolina reflected:

Students are not having the opportunity to explore and master a concept before they are being assessed.

A Connecticut-based early childhood teacher with over 30 years of experience commented:

Everything that is taught is taught [at] an earlier age. It is frightening to see what is expected of young students. I became a teacher because I loved school. I wanted children to love school as well. When I talk to young children and ask them what they like about school, so many say, ‘I hate school.’ This comes from many kindergarten children. That is very sad. If you are going to love school at any time, you should definitely LOVE being in kindergarten.

The data from this online survey of early childhood educators reveals that teachers of young children in general do not feel that current education policy mandates are benefiting children. Public school teachers expressed concerns in greater numbers than did private school teachers, whose programs are not dependent on federal and state funds that mandate standards, testing, and accountability.

This leads us to conclude that children who attend private preschools receive a curriculum better grounded in play-based learning and child development principles, and this was reflected in the survey. Poorer children, because they are more likely to attend publicly funded programs, receive an education that is more inappropriate developmentally; they have less time for exploration, play, and active learning, and spend more time in direct instruction and with inappropriate testing.

Put simply, it is our poorest children, those attending publicly funded programs, who are receiving the most inadequate early education. Yet these are the children who should be receiving the very best early childhood education we can offer–enriched classrooms with the best teachers, grounded in the best of what is known about how children develop and learn.

The 185 teachers who responded to this survey are the canaries in the coal mine and we should pay attention to what they are saying. There is almost no research reporting on the effects of Federal and state mandated early childhood school reform. There is also very little data on how those trained to work with young children feel about the reforms. We hope that this DEY report of a small sample of early childhood educators’ malcontent and concerns will trigger more far-reaching research efforts about what optimal early childhood education should be for all children, and especially for those from low income families.

Leave A Comment