Illustration by Andreas Samuelsson. Photograph by Thomas Hannich

When old is new again and new is old the conversation must be about education. Throughout our history people have fought for the right to educate all equally and then turned the mission over to the masters, the moguls, and the moneyed. Public education, we say is our priority. But we do not fully invest; we divest our interest. We live by the sword and die by it. We choose to forget or forego what we know; big money makes education a business. In 2008, The New York Times recounted the long history of wealthy Americans wielding power in and over education. It was observed that the landscape changed or did it. “How Many Billionaires Does It Take to Fix a School System?” One venture philanthropists, two? Three might do. And what of the people? Did they give up their power, when, how, and why? Perhaps the belief is billionaires are the experts…they know how to make money and therefore can best shape our future, our children, and education, or can they?

When Billionaires Become Educational Experts

“Venture philanthropists” push for the privatization of public education.

For years, critics have pointed to the decreasing ability of health-care professionals to make decisions and provide services because of the demands of insurance companies and health-management organizations to sustain profits. Health-care decisions are increasingly being made by the wrong people and for the wrong reasons.

So, too, with public education. Current reforms are allowing certain individuals with neither scholarly nor practical expertise in education to exert significant influence over educational policy for communities and children other than their own. They, the millionaires and billionaires from the philanthropic and corporate sectors, are experimenting in urban school districts with educational reform initiatives that are not grounded in sound research and often fail to produce results. And yet, with funding for public education shrinking, the influence of these wealthy reformers is growing.

There is also much profit to be earned from public education. The American educational system today is a $500–600 billion enterprise, funded overwhelmingly by public dollars, with billions of dollars in services and products being outsourced, and with political lobbying groups like the Democrats for Education Reform, financed by hedge-fund millionaires, leading the push to further outsource. The public educational system has always had ties to the business sector, including business leaders themselves and the philanthropies funded by business fortunes. But that influence has not always looked the same. Despite the fact that philanthropic giving has never constituted more than 1 percent of total educational funding, in recent years a handful of millionaires and billionaires have come to exert influence over educational policy and practice like at no other time in American history. What has happened? The roles of business and philanthropy have shifted, reconfigured, and converged over the past century, and therefore seeing the bigger picture of public education requires understanding the interrelated histories of philanthropic and corporate influence.

Early Corporate Influence

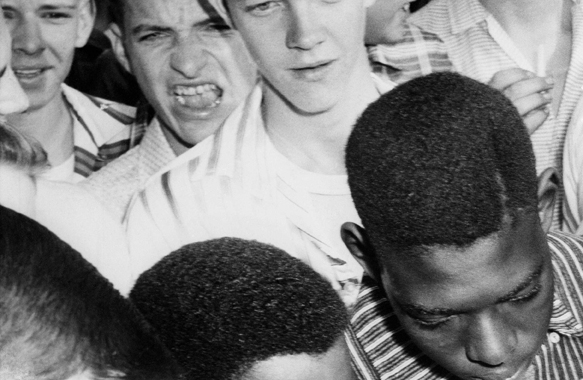

Philanthropies have a long history of giving to public education, a history that includes early efforts by white businessmen to shape the education of communities of color. Following the US Civil War, for example, philanthropies helped to establish primary and vocational schools for African Americans in the South, as well as normal schools that eventually became black colleges and universities, which expanded access even as they reinforced segregated and differentiated learning. In the first half of the twentieth century, philanthropies supported and expanded the use of intelligence testing that justified a racialized understanding of what different groups of students could learn and do, making commonsensical the notion of academic tracking. Clearly, the early philanthropies were varied in their goals and impact, funding initiatives that both reinforced and challenged inequities in education. But these philanthropies, perhaps the best known of which were the Carnegie Corporation, the Ford Foundation, and the Rockefeller Foundation, increasingly tried to raise the visibility of educational inequities and thus were widely perceived as liberal and altruistic for much of the twentieth century.1

The business sector also has a long history of influencing public education, particularly in the period from 1890 to 1940, when public school districts were consolidating and becoming larger and larger. As immigration made cities increasingly diverse, and as members of the working class won more and more seats in city governments, the business elite made concerted efforts to take control of local school boards, not only by getting business leaders elected to school boards but also by structuring the boards to reflect the centralized control and bureaucracy that characterized the large industries that were emerging at this time. That is, the business elite influenced school governance both by constituting its governing bodies and by structuring its model of management. The business elite turned its attention to higher education as well, as in the 1950s when the US Chamber of Commerce and other corporate advocates began creating a network of organizations on university campuses that aimed to cultivate probusiness values in the next generation of leaders.2

Philanthropy and Business Roundtables

As the United States entered the second half of the twentieth century, significant economic, legal, cultural, and ideological changes occurred that would prompt the formation of new structures in both the philanthropic and the corporate sectors. In the early 1970s, two national groups emerged that would have enormous influence on public policy generally, and educational policy in particular, in the decades to follow: the Philanthropy Roundtable and the Business Roundtable.

First, the Philanthropy Roundtable. The 1950s and 1960s were a time of numerous and significant legal and cultural challenges to inequities of race, class, and gender. The civil rights movement brought together a range of constituents to push for landmark legislation and policy changes across the nation. To opponents of the civil rights movement, such attempts at resource redistribution and governmental regulation departed from the American ideals of self-sufficiency and meritocracy and in the process threatened to weaken the American economic system of “free enterprise.” Opponents also took note of how such legal changes were led by a “liberal establishment” that was organized and strategic in ways that conservatives were not yet.

In 1971, Lewis Powell, who would soon after become an associate justice on the US Supreme Court, wrote an internal Chamber of Commerce memorandum known as the “Powell Manifesto.” This memorandum described a concerted liberal attack on the American free-enterprise system and on American democracy itself and called for organizing and action. In response to the Powell Manifesto, a group of conservatives, particularly philanthropists with family business fortunes, came together and formed a national roundtable that would strategize about how to use their personal wealth for conservative movement building.

At the helm were wealthy conservatives whose philanthropic work helped to seed what eventually grew into an interconnected web of organizations and initiatives. Their project was as much legislative as it was ideological, in that they aimed to influence legislation and policy as well as to shape “common sense” in society. In the decades to follow, the conservative philanthropies developed interconnected funding priorities and strategies to advance publicpolicy agendas that favored business and opposed social welfare and that would enable the American political and economic systems to continue to benefit those racial and social-class groups that were already privileged in society.

They sought to develop a cadre of students in higher education who embraced conservative ideologies, a generation of scholars who produced research that would make conservative ideologies accessible and who would then enter government service, a network of regional and state policy think tanks and advocacy organizations, and a protocol for using the media to reach the public effectively.3 Their strategies have been quite successful, as evidenced by the emergence of such public figures as Dinesh D’Souza, Chester Finn, Newt Gingrich, and Thomas Sowell, all of whom were once beneficiaries of fellowships and other forms of professional support from the philanthropies, as well as by the preponderance of messages in the media and legislation that were developed in related think tanks.

At the top of the chopping block was public education, considered by some to be a drain on the government and a crutch for society not only because it was the most expensive of domestic enterprises but also because it exemplified what they considered to be a socialist enterprise. Conservatives called for the entire school system to be privatized, made into a free enterprise, and the conservatives’ strategy of choice was school vouchers. Early on, Milton Friedman, one of the leading proponents of free-market reform, argued that “vouchers are not an end in themselves; they are a means to make a transition from a government to a free-market system.” Not surprisingly, the focus of many conservative foundations has been and continues to be school-choice and school-voucher initiatives.

Until recently, the four most influential conservative foundations nationally were the Bradley, Olin, Scaife, and Smith Richardson foundations, sometimes dubbed the Four Sisters. The Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation in Wisconsin is the country’s largest conservative foundation and includes among its priorities the ending of affirmative action and of welfare. A former board member is William Bennett, secretary of education under President Reagan. The Bradley Foundation is involved in various educational policy initiatives, including the support of school-voucher programs and privatization. The John M. Olin Foundation, which ceased operations in 2005, focused on developing research through think tanks as well as through higher education, with large gifts to Harvard, Yale, the University of Chicago, and other universities, as well as to individual researchers.

The Scaife Family Foundations, consisting of the Sarah Scaife, Allegheny, and Carthage Foundations and funded by the Mellon family fortune, gives to a range of think tanks and lobbying and publishing groups. The H. Smith Richardson Foundation in North Carolina supports, according to its website, the “next generation of public policy researchers and analysts” by funding think tanks and universities. All of the Four Sisters have contributed funding to the leading conservative think tanks, including the American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, the Heritage Foundation, and the Hoover Institution.

Several other foundations gave more than $100 million to conservative causes between 1998 and 2004, including the Walton Family and DeVos foundations. Created by the heirs of Sam Walton of Wal-Mart, the world’s largest corporation, the Walton Family Foundation in Arkansas has financed nearly every ballot initiative for vouchers since 1993. Walton funds such provoucher organizations as the Alliance for School Choice, as well as organizations that draw communities of color into the provoucher movement, such as the Black Alliance for Educational Options and the Hispanic Council for Reform and Educational Options. The Richard and Helen DeVos Foundation in Michigan, funded by the AmWay fortune, supports vouchers as well as organizations of the Christian Right, including Focus on the Family, which have vast media and communications resources. More recently, the Charles Koch Foundation has targeted higher education by funding faculty positions, think tanks, and educational initiatives in universities across the country. The websites of the Media Matters Action Network (http://mediamattersaction.org) and People for the American Way (http://www.pfaw.org) provide descriptions of these and numerous other such foundations.

Of course, conservative foundations are not the only ones funding education. Liberal philanthropies that identify with the goals and legacy of the civil rights movement also contribute to education, but they are far less visible and influential in changing federal or state-level policy. Perhaps the most notable strategic difference between conservative and liberal philanthropic organizations is the expectation of how organizations will use their funds. Whereas the liberal philanthropies tend to fund a large number of organizations for specific projects of limited term and scope, the conservative ones are more likely to fund the general operations of a smaller number of organizations over longer periods of time in order to build institutional infrastructure. The conservative foundations especially direct funding to organizations that aggressively lobby in state legislatures and Congress and that engage effectively in media campaigns, thus ensuring that their ideas are enacted into law with public support. Consequently, the conservative movement has emerged as an interconnected web of organizations with aligned missions and coordinated strategies, often facilitated by shared board members.4

The history and function of the Business Roundtable parallel those of the Philanthropy Roundtable. The 1960s were marked by declining corporate profits resulting from such factors as deficit spending to fund the war in Vietnam, rising oil prices following the formation of OPEC, and an increasingly competitive market in a globalizing economy.5 The decade also saw increasing governmental regulation of the workplace and increasing influence of organized labor. In response, some business leaders felt the need to organize the corporate sector in order to influence public policy in ways that advanced corporate interests, particularly the interests of the business elite. In 1972, the Business Roundtable formed, consisting of the top three hundred CEOs in the nation.

The Business Roundtable had always addressed a range of public policies, but in the late 1980s it began focusing significant attention on public education. In 1989, it called for six “national education goals” and, soon after, nine “essential components of a successful education system.” This call put pressure on states to move toward an outcomes-based model of educational reform, using standardized tests to measure student and teacher performance, with sanctions and rewards for failure or success. Reinforcing the pressure put on states was a large network of influential foundations, centers, universities, and public media, assembled by the roundtable, that consisted of such entities as the Annenberg Center, the Broad Foundation, the Education Trust, Harvard Graduate School, and most newspaper editorial boards.

In so doing, the Business Roundtable effectively laid out a blueprint for standards-based reform, begun during the Reagan administration but culminating in the 2001 No Child Left Behind Act, which has become so taken for granted as the way to think about educational quality and educational reform that even Democrats, from Clinton onward, have put forth proposals that were framed by these concepts.

Venture Philanthropy

As the United States neared the end of the twentieth century, the globalizing economy provided fertile ground for an unprecedented accumulation of wealth by the corporate elite. Taking this new wealth and the lessons learned about leveraging wealth for both increased profits and political influence, several millionaires and billionaires transformed the landscape of philanthropy, developing new organizations that operate much more like the conservative foundations than traditional philanthropies. These are the venture philanthropies.6

Unlike traditional philanthropy, which sought, at least in principle, to “give back” to society, venture philanthropy parallels venture capitalism in its goal of investing capital in ways that earn more. In contrast to venture capitalism, one benefit of venture philanthropy is that it operates under different incorporation laws, providing tax shelters for what are really financial investments. Whereas the financial returns may not be as immediate as those of corporate transactions, the policy foci of today’s venture philanthropists indeed reveal the economic incentive of their investments. They overwhelmingly are pushing for the privatization of public education, creating new markets worth hundreds of billions of dollars, as well as for the prerogative to direct how public tax dollars get spent. They target the large urban school districts, experimenting with models they hope eventually to “scale up” nationally, as they have done in Chicago, where the Gates Foundation alone has spent millions on small-school initiatives, school turnarounds, youth organizing, and parent organizing.7

Another departure from traditional philanthropy is the role that venture philanthropists play in their investments. Whereas traditional philanthropists view their giving as donations that support what others were doing, venture philanthropists view their giving as entryways into that work. That is, philanthropists themselves are now getting significantly involved in goal setting, decision making, and evaluating progress and outcomes to ensure that their priorities are met. This hands-on role allows venture capitalists to affect public policy more directly and substantially, particularly in a climate where their financial aid is so desperately needed.

Indeed, the timing was fortuitous for venture philanthropy. Setting the stage was the 1983 report by the Reagan administration, A Nation at Risk, which claimed not only that public schools were failing but also, more significantly, that their failure was a primary cause of the nation’s economic recession at that time. Such a crisis gave the business elite yet another reason to turn their attention to public education. And for their part, educational leaders needed the additional funding because fewer and fewer tax dollars were being earmarked for education. States have been disinvesting in education for decades: over the past twenty years in Illinois, for example, state contributions to public higher education dropped from almost 50 percent to less than 20 percent of university budgets. Cities and districts have also been disinvesting: from the 1980s through the 1990s, the federal government reduced its funding to cities, and, when combined with the global financial crisis of the past few years, this reduction in funding provided cities and districts new justification to slash education budgets further, resulting in the current furloughs of public school teachers and staff, shortened school years, reduced services and resources, and reduced educational quality. This was the result not only of less money, caused in large part by dramatically decreasing taxes paid by corporations and the wealthy, but also of lower priority being placed on education at a time when budgets for prisons and wars were steadily increasing.

Such cuts, of course, disproportionately affect students of color and working-class students, who disproportionately populate the public schools and public universities, which brings us full circle to the time of the early philanthropies when white businessmen were using their wealth to change the education of primarily poorer students of color, often with even greater disparities resulting. The change is not only in educational policy but also in public-policy decision making more broadly, signaling the transition from public deliberation by an elected government to decisions of self-appointed individuals with no accountability to the public.

The two leading venture philanthropies, the Gates Foundation and the Broad Foundation, do include among their grantees historically liberal organizations like the teacher unions. However, their funding priorities and strategic initiatives are so framed by neoliberalism, and their partnerships with conservative organizations and leaders so extensive, that their impact is indistinguishable from that of the conservative foundations. Overwhelmingly, by number of initiatives and amount of funding, the leading venture philanthropies are emphasizing the privatization and marketization of public education with such initiatives as outsourcing of school management, which can best be seen in school districts that are targeted for charter- school growth, where the majority of charter schools are managed by for-profit companies; incentive pay for teachers; alternative routes to certification for teachers and school leaders; and school-choice and charter- school initiatives. The leading venture philanthropies are investing in a web of organizations not unlike the web of foundations, think tanks, media organizations, and advocacy groups that characterizes the conservative network. The Gates Foundation, for example, funds think tanks like the American Enterprise Institute to issue reports, communications groups like Teach Plus to amplify the voices of teachers who specifically counter the voices of the teacher unions, and leadership groups like the National Governors Association and the Council of Chief State School Officers to develop policies around the common-core standards.

The top-giving venture philanthropies include a broad mix of foundations from family fortunes: the Broad Education Foundation, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Walton Family Foundation, the Michael and Susan Dell Foundation, the Donald and Doris Fisher Fund, and the Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation. These megaphilanthropies are funding other education-related venture philanthropies, like the Charter School Growth Fund and the NewSchools Venture Fund. Venture philanthropies include not only the national foundations from individual family fortunes but also the local philanthropies that were founded by collectives of business leaders, as is the case in Chicago with the Chicago Public Education Fund and the Renaissance Schools Fund. The result is a philanthropic sector that is inseparable from the business sector, advancing school reforms that cannot help but to be framed by corporate profitability.

Kevin K. Kumashiro is professor of Asian American studies at the University of Illinois at Chicago, where he was formerly chair of educational policy studies. He is president-elect of the National Association for Multicultural Education. His e-mail address is kevink@uic.edu.

This essay was adapted with permission from Bad Teacher! How Blaming Teachers Distorts the Bigger Picture. © 2012 Teachers College Press. All rights reserved.

Notes

1. William Watkins, The White Architects of Black Education: Ideology and Power in America, 1865–1954 (New York: Teachers College Press, 2001).

2. Anuradha Mittal and Felicia Gustin, Turning the Tide: Challenging the Right on Campus (Oakland, CA: The Oakland Institute and the Institute for Democratic Education and Culture—Speak Out, 2006); David B. Tyack, The One Best System: A History of American Urban Education (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1974).

3. Kathleen deMarrais, “’The Haves and the Have Mores’: Fueling a Conservative Ideological War on Public Education (or Tracking the Money),” Educational Studies 39, no. 3 (2006): 201–40.

4. Jeff Krehely, Meaghan House, and Emily Kernan, Axis of Ideology: Conservative Foundations and Public Policy (Washington, DC: National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy, 2004).

5. David Hursh, “Assessing No Child Left Behind and the Rise of Neoliberal Education Policies,” American Education Research Journal 44, no. 3 (2007): 493–518.

6. Kenneth Saltman, The Gift of Education: Public Education and Venture Philanthropy (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010); Janelle Scott, “The Politics of Venture Philanthropy in Charter School Policy and Advocacy,” Educational Policy 23, no. 1 (2009): 106–36.

7. Pauline Lipman, The New Political Economy of Urban Education: Neoliberalism, Race, and the Right to the City (New York: Routledge, 2011).

Leave A Comment