Photograph; M.K. Nguyen ends the protest with a Unity Chant as groups protest on the median in front of Sarah T. Reed High School to protest school closure, Monday, December 9, 2013. (Photo by Ted Jackson, Nola.com | The Times-Picayune)

By Danielle Dreilinger | Originally Published atThe Times-Picayune. May 13, 307 PM

A national coalition on Tuesday filed a federal civil rights complaint alleging Louisiana’s school closure policies discriminate against black children. It says the state shuts down conventional New Orleans schools that are almost entirely black even when they show improvement, while giving poorly performing white schools a pass. Displaced students then have unequal access to the city’s best public schools, which are heavily white and allowed to use admissions policies that exclude black students.

“In essence, the state has robbed these children of their neighborhood schools while keeping them trapped in failing, under-performing schools,” says the complaint, filed by local activists and backed by the Advancement Project, Journey for Justice and the country’s two largest teachers unions: the American Federation of Teachers and the National Education Association. The Louisiana Department of Education, Board of Elementary and Secondary Education and Recovery School District are named as defendants.

The Recovery School District objected to the criticisms. The state education board would not comment.

The complaint aims to stop the closure of the Recovery School District’slast five conventional schools next month: Benjamin Banneker Elementary, A.P. Tureaud Elementary, George Washington Carver High, Walter L. Cohen High and Sarah T. Reed High. It also demands a moratorium on charter school renewals.

The coalition also filed complaints against Newark, N.J., and Chicago. It timed the action to mark the 60th anniversary of the Brown v. The Board of Education of Topeka, Kan., decision, the Supreme Court ruling that struck down racial segregation in public schools.

Closing and chartering schools “is the new Jim Crow,” said co-author Karran Harper Royal.

In the months after Hurricane Katrina, the state Recovery School District took over more than 80 percent of New Orleans’ public schools. Initially, the state district ran some schools directly, but as of this summer, all the schools it reopened will have been closed or chartered. The Orleans Parish School Board controls 19 schools, 14 of them chartered.

The national coalition’s New Orleans initiative is led by the Coalition for Community Schools and Conscious Concerned Citizens Controlling Community Changes, which include many longtime critics of these changes. The national partners oppose charters, which are publicly funded but run by private organizations.

About 30 New Orleans representatives traveled to Washington to rally on the steps of the Supreme Court, said attendee Minh Nguyen of VAYLA New Orleans. His group has tried to halt the closure of Reed High, in eastern New Orleans.

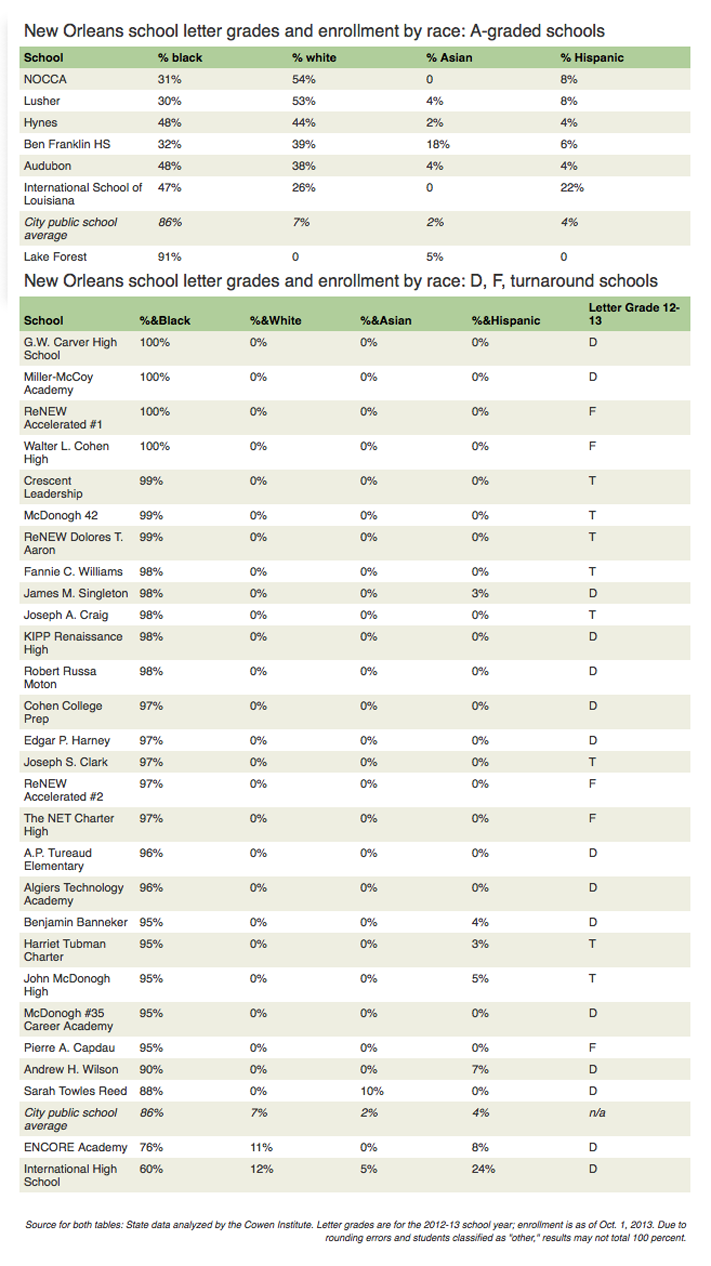

Undeniably, New Orleans’ successful public schools are far more white than the norm, while its grade D, F and turnaround schools are almost entirely black. The city’s public school average enrollment is 86 percent black, 7 percent non-Hispanic white, 4 percent Hispanic and 2 percent Asian, according to analysis by Tulane University’s Cowen Institute for Public Education Initiatives.

Of the city’s seven A-rated schools, only one – Lake Forest in eastern New Orleans – has more black students than the norm. The others range from 26 percent to 54 percent white enrollment.

Conversely, only two of the D, F and turnaround schools have any white students at all: International High and Encore Academy. Neither is in the Recovery School District.

The complainants question why the Recovery School District closes conventional schools even when they have improved, as have four of the five that will close next month. Murray Henderson Elementary, which was more than 98 percent black, had good test scores in 2013, but the state closed it anyway.

Meanwhile, International High, which is 60 percent black and 12 percent white, has been allowed to remain open despite low test scores, the complainants write. Nor did Louisiana revoke the charter of Lycée Français, 14 percent black, despite major management issues in the school’s first two years.

Those closures reach beyond students and parents, the complainants write. “The state’s decision to close these neighborhood schools robs us of these critical institutions, the relationships they hold and the much-desired stability they provide. It sentences our communities to a slow and painful death.”

The Tureaud closure is especially stinging, because its namesake led the NAACP’s legal fight for New Orleans school integration.

Perhaps the most striking part of the complaint is the contention that disproportionately high white enrollment in the city’s very top schools constitutes discrimination and is a result of policies that keep black children out. Several of those schools have been exempted by the Orleans Parish School Board from using OneApp, the city’s centralized school enrollment process for both school systems. “As a result, many parents do not know about them,” the complainants write, citing interviews with Tureaud parents.

OneApp has become an instrument for exclusion because the best schools aren’t on it, according to the complaint. Those schools also often have admissions criteria “that disproportionately exclude African-American students.” They include entrance assessments at Ben Franklin High, Audubon, Lusher and International School; narrow neighborhood preference at Lusher and Hynes, which are in white areas; and preference to certain universities’ faculty at Hynes and Lusher.

No matter what the state might say, “the racial disparity caused by RSD’s policy of school closures, authorized by BESE and implemented by LDOE, provides circumstantial evidence of intentional discrimination,” the complainants write.

In all three cities where it filed complaints, the activists demand public input in future changes. “The one thing that would be actually revolutionary would be to work with the community,” said Jitu Brown, Journey for Justice national coordinator, echoing a common local complaint about the Recovery School District.

Recovery School District spokeswoman Zoey Reed pointed to its schools’ “tremendous progress by any academic measure — ACT scores, student achievement, graduation rate.” The city has almost caught up with the state test score average and the number of graduates qualifying for TOPS tuition coverage has increased from 25 to 38 percent.

“It is critical to insist on the civil rights of every child, and there is no doubt New Orleans is closer to assuring those rights than it was a decade ago,” she said.

Leave A Comment