Some of the students who led protests over the district’s Collegiate Academy charter schools withdrew from those schools and enrolled in Liberation Academy, founded by parents and local activists.

By Jordan Flaherty| Originally Published at The Root. May 13 2014 3:00 AM

Every year hundreds of young, idealistic recent college graduates flood into New Orleans to teach at the city’s public schools. But in a school system where the vast majority of students are African American, the mostly white influx of new teachers has brought complaints of racism and cultural insensitivity, and helped birth a new student-led protest movement.

African Americans are about 60 percent of New Orleans’ population (down from 67 percent before Hurricane Katrina) but make up 88 percent of the city’s public school system. White students are clustered at a handful of high-performing schools, and other ethnicities make up only small portions of the system, so most schools are almost entirely African American. Before Hurricane Katrina, most teachers were black women, mostly from New Orleans and often from the neighborhoods of the schools in which they worked.

But in the weeks after Hurricane Katrina, the entire staff of the school system—about 7,000 teachers and other employees—was laid off, their contract was ignored and their union was powerless to help. Katrena Ndang, who worked for 17 years as a teacher in New Orleans, found out she’d been fired while watching the news after being evacuated. “Even though we had given them forwarding addresses, they never sent us notice,” she says.

This January the Louisiana Court of Appeal affirmed an earlier ruling that found the teachers were wrongly terminated. But the school system, now almost entirely charter, looks very different from the one from which the teachers were dismissed. And one of the major changes was the entry of thousands of new teachers, many drawn from elite colleges and universities.

For nearly a decade, New Orleans has been one of Teach for America’s main sites. The organization sends about 400 teachers to the district per year, while 32 of TFA’s alumni are school leaders in New Orleans, and many others are designing curricula and shaping city and state policy. Before 2011, only 5 percent of these new teachers were African American. That number has gone up to 15 percent, with 31 percent of teachers overall now of color, according to local TFA spokesman Chris Bertelli.

came in with the attitude that they

were coming in to change

the culture.

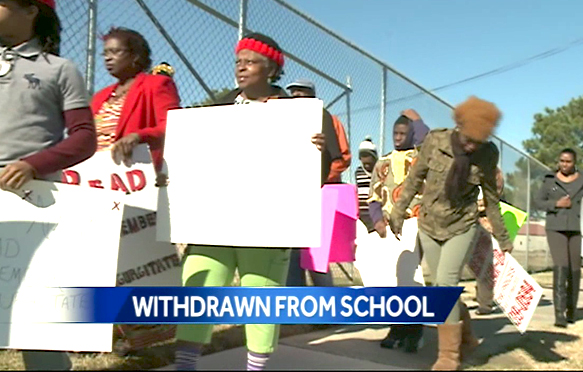

As the teachers are pushed out, many of their former students complain that they have lost good teachers and role models. A wave of student-led protests began in October 2012, when students at one high school marched in protest over the firing of veteran teachers. Jonshell Johnson, 16, helped organize the protests through a group called United Students of New Orleans. “Most teachers that were being fired, we had built strong relationships with. They knew our parents,” she says. “We asked them what’s wrong, and they said they were being pushed out. We said, ‘If they’re hurting you, they’re hurting us.’”

Jonshell remembers one particular veteran teacher as being “really interactive and passionate.” But this teacher was replaced with a 24-year-old white teacher whom students found difficult to relate to. “Students couldn’t understand her vernacular,” says Johnson. “She talked like she was still in college.”

Jonshell says that many students need help with issues outside of school. “There is a lot of distrust of social workers, so many students turn to teachers,” she says. But when students went to the new teachers, they seemed unresponsive. “It’s more like they’re reading from a rule book.”

She also found that the new, younger teachers seemed to be overly caught up in the partying culture of New Orleans, taking extra days off during Mardi Gras season and other festive holidays. “When a teacher misses three or four days a week, what example does that make?”

The protests resumed this school year, with one student statement of demands addressing the lack of diversity in the teaching ranks (pdf):

There are no black teachers. The only black role models we have at the school are janitors, cafeteria workers, secretaries, security guards, and coaches. Some of the teachers are racially insensitive. None of the teachers are from New Orleans. They can’t relate to us, our neighborhoods, or our community. They have no respect for our customs and culture, and simply want to make us more like them without understanding us and our background.

On April 15, lawyers filed a complaint on behalf of parents and students at three schools run by a charter operator called Collegiate Academy. At the top of the 15 grievances listed was the issue of suspensions. Over the course of one year, 68.85 percent of students at one of the operator’s schools, Carver Collegiate, were suspended—the highest rate in the city. Suspended students are often sent home without their parents being informed, which also makes this an issue of student safety.

In addition, the grievance describes the bullying and harassment of children with special needs by teachers and administrators, male teachers’ walking in on female students in the bathrooms, and school administrators’ withholding of meals from students as punishment, in addition to intimidation and retaliation against students who speak up about these abuses—including those who led the protests.

As the targets of much of the student anger and resentment, many of these new teachers acknowledge their inability to relate to their students. Hannah Sadtler came to New Orleans in 2008 as a Teach for America recruit. At her school, there were only four veteran teachers; the rest were new arrivals. Like her, almost all were white.

disrespected my students and their

families must have felt by me.

Sadtler helped found an organization called the New Teachers’ Roundtable, which seeks to address some of the challenges highlighted by the student protests. She is bringing new teachers together with veteran teachers, parents and students for in-depth dialogue.

Sadtler hopes that she can change a system that puts idealistic young people in conflict with a community that they should be learning from. “I feel incredibly sorry for how disrespected my students and their families must have felt by me,” she says, “the posturing, playing teacher when I wasn’t one. I think the only way that I was able to buy into that—to maintain that position and stand in front of those kids—was because of internalized messages of superiority that I bought into.”

Sadtler estimates that her organization has reached nearly 400 teachers out of about 3,000 in the school system overall, and more than 100 have become deeply involved in the roundtable’s work of outreach and dialogue.

Teachers as well as students are in rebellion against the current system, with both groups focused on the goal of an excellent education that comes out of a respect for the students and their culture. Jonshell Johnson says that the activism she has been involved in has shifted the dialogue in the city, and through her organizing she continues to be in touch with students in schools across the city, talking about issues like school discipline. “A lot of administrators are aware of us,” she says. “Now they ask us. We are kind of like a requirement. I don’t want to say we’re a threat, but we have influence.”

Jordan Flaherty is a journalist based in New Orleans and the author of Floodlines: Community and Resistance From Katrina to the Jena Six.

Leave A Comment