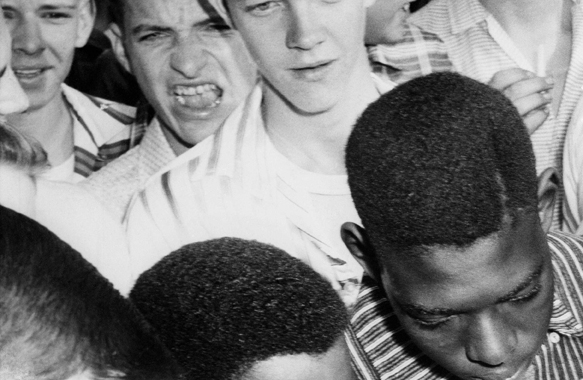

Photograph; Newark Schools Superintendent Cami Anderson, right, meets with Dashonnah Gittens, left, and fellow junior Armani Stevenson at an event last fall. (Aristide Economopoulos/The Star-Ledger)

One more community is torn asunder. The Newark New Jersey School District was not the first; nor will it be the last to convert public education into private charterization. We see the trend everywhere; it takes place in Chicago. Detroit too. Philadelphia is not exempt. In New Orleans it is called Recovery , only it isn’t. Regardless, throughout the country it is underway.

The signs signal change. “Reconstruction in Progress.” Put Charters in Place. “New and Improved” “public” schools! “Come one and all,” city officials exclaim, “We bring you options.” Of course, there is the disclaimer. The print is small and placed at the bottom – “Choice is brought to you by corporatization.” Welcome to America., where public education and the freedom to choose

Is Newark’s Restructuring the latest or the greatest? Neither; it just is what it is, archetypal. America’s devolution. Schools serve, selectively. Parents are confused. Transition is remission, and progress…well, that depends on your perspective. Do you align supply with demand or demand with supply and who chooses? The supplier, the demander, or those served?

Newark School Restructuring Includes Plans To Put Charters In District Buildings

As part of a comprehensive plan to overhaul the state’s largest school district, Newark Schools Superintendent Cami Anderson wants to increase access to charter schools by expanding them into district-owned buildings.

The district also plans to convert three elementary schools into early childhood centers, relocate five schools to under-utilized facilities and transform three comprehensive high schools into smaller academies. The goal, Anderson said, is to improve local options for all residents.

“You should have options for great schools in your neighborhood or ward,” Anderson said. “How do we get to that day faster and in every ward? We’re jump-starting change.”

District officials are talking with officials from the TEAM, North Star and Newark Legacy charter schools and asking them to locate their additional classroom spaces to the Madison Avenue, Hawthorne Avenue, Bragaw Avenue, Alexander Street and Newton Street schools. At least three facilities, including Miller Street, would be shuttered.

The district would also designate nine facilities as “renew” schools, allowing their principals to rehire faculty and staff of their choosing. In all, the changes would involve more than one-third of the district’s schools.

The hot-button issue, however, is moving charter schools into district facilities.

“We’re asking them to align supply with demand,” Anderson said. “Let’s play to the strengths we have.”

Opposition to the proposal was on full display last night when a raucous crowd packed the auditorium of the Park Elementary School for a School Advisory Board meeting. Parents and teachers heckled until Anderson stopped her presentation. Several people were escorted out.

Union leaders accused Anderson of pushing charters while ignoring the traditional district schools.

“We don’t have a superintendent for the traditional schools. The charter schools have a superintendent,” said Joe Del Grosso, president of the Newark Teachers Union.

Del Grosso also dismissed the idea that the district doesn’t have the ability to fix the crumbling buildings. “They are all repairable,” he said. “Once these schools are gone, Newark will never get them back.”

The changes have families confused.

“First we were informed it was going to be closed, now it’s going to be turned into a charter school. It’s a very big concern,” said Iris Torres, president of the Parent Teacher Organization at Bragaw Avenue School, where her two granddaughters are enrolled.

Charter school leaders say the details of any plan are still being worked out.

“We haven’t agreed on anything with the district yet,” TEAM executive director Ryan Hill said. “We have some general areas of agreement, but in terms of (details) it is far from being concluded.”

Hill said TEAM charter school is willing to serve students in a particular enrollment area, so working with a specific school neighborhood would not be a hurdle. “But if we go into a district school it wouldn’t necessarily mean we take over all the grades in that school,” he said.

In fact, Hill said, the TEAM model would expand one grade at a time. “We build slowly, so we can build the culture of the school,” he said. “Very deliberately, that’s what our six schools in Newark are doing.”

Mashea Ashton, CEO of the Newark Charter School Fund, applauded the proposal because it continues the collaboration between the independent but publicly funded charters and the district.

“It acknowledges that charter schools are part of the solution, and that’s reassuring and consistent with our work with the superintendent over the last year,” Ashton said. “It’s really about increasing access.”

Robin Lake, director of the Center on Reinventing Public Education at the University of Washington, said officials in Denver and Washington, D.C., are considering similar agreements wherein the district turns to charter schools to help turn around struggling schools.

“It happens in a lot of cities. Charters pop up where buildings are available and that doesn’t always match up with neighborhood demand,” she said. She noted, however, tensions could arise when charter schools are placed in neighborhoods that may not be receptive to them.

New Jersey Charter Schools Association president Carlos Perez said the plan to shift district schools to charters makes sense. “If the initiative works and it provides families with high quality options that they wouldn’t previously have had, I don’t see how you can be opposed to it.”

But change won’t be easy. Shakirah Miller-Harrington is principal at the Miller Street School, which may be relocated to the Louise A. Spencer School, because the Miller Street building has constant heating, flooding and plumbing problems. “We understand, but we want to patch it up,” she said. “We want to stay.”

Introductory Essay By Betsy L. Angert

Leave A Comment