Photograph; Angel Nevins, center, and her friend and classmate Jade Smith, left, wait for their signal to ring their hand bells as children from the Anderson Grove Head Start program in Caledonia, Mississippi, ring their hand bells to accompany several patriotic songs, Tuesday, February 26, 2013, at the Capitol in Jackson, Mississippi.

By Betsy L. Angert | Originally Published at EmpathyEducates. January 2, 2013

Wherever we go we hear the roar. It is Common Core. “Common Core is a threat to our democratic system,” or is it? Common Core ignites. It incites. Surprisingly, it also unites the citizenry. It seems, at last, people of every political persuasion can agree. “Common Core, No. It is not for me!” Can that possibly be? There is another contention. “You have it wrong.” “I have a right.” Let us have another fight and forget what might be our forebearers intention – our responsibility to the Seventh Generation.

Children are the Common Core, and their Common Core is we. We are the center of their world. There is profound connection. Mother and child, Father and son – Daddy’s little girl, all are equally significant. What is unique is the difference. A child looks to his/her parents to learn, who am I and what will I be. We call this identity.

Mom and Dad may preach, but through their actions they more authentically teach. The children are watching. What will we do? How we respond; they will too.

The loss of a job. A much reduced income. Recession. Depression…and oh yes, there is omission. A vibrant and productive person separated from his or her profession is left out, left behind and there is many a misimpression. Some people say the unemployed are just lazy. Their perception must be hazy, or could it be that the out of work are just crazy? After all, look at the classified ads, there is tons of work. What is all too common cuts to the core. Adults are not the only ones affected. It is you and me, but more so, the little ones at our knee.

When a parent loses a job, the entire family is affected, including the children. Money is suddenly tighter, and what was affordable last month, no longer is. Even children who are too young to be aware of financial adjustments may pick up on a change in the family atmosphere. Adults may be arguing more frequently, and parents may speak more sharply to their children. While children may benefit from their parents spending more time at home, the downsides of parental unemployment—the loss in family income and increase in parental stress—tend to overshadow such potential benefits, leaving children worse off when one of their parents loses a job.

The jobless might cry, and their children will tear. But no one will hear. Their shouts will be drowned out by the privileged. Oh how they preach about what not to teach. “Stop Common Core State Standards before it is too late. Our children will be deprived. Privacy denied. Punitive measures will be put in place. There is much to deride and more to decide.

While we debate and deliberate, over how instruction might be best delivered the jobless stew. Their children brew. And we? What will we do? Perhaps it is time to come to terms and invite a broader perspective. Common Core is so much more…It is you and me, and the children make three. Yes, there is a connection – Unemployment. Unemployment, and the lack of emergency unemployment insurance, hurts our young. Children are Left Behind. With a parent’s Job Loss comes is a discernable effect on our youth. Student Achievement drops precipitously, as does peer interaction. The stark reality is the child of a jobless parent knows that s/he cannot afford to join the club. The cost associated with dues or just the price of rejection can be too great to bear.

Belonging is what really matters. “When children feel a sense of belonging and a sense of pride in the families, their peers, and their communities, they can be emotionally strong, self-assured, and able to deal with challenges and difficulties. This creates an important formulation for their learning and development,” at least, that is when a sense of belonging exists. When it does not, our identity is threatened. Identity cements our Common Core more than a curriculum might.

Common Core is so much more than a means for delivering instruction. It is compassion. It is what today, we ration. Sadly, too many work to deny that ‘there by the grace of God go I.”‘ Instead we embrace vociferous contention.

We forget that we began with a dream. The most crucial one being, I will belong. I will go to school, study hard, and become an incredible success. My career will provide me the resources so that I too might contribute to the greater good, the commonweal, the Common Core. And yes, that is the connection.

That dream was not a mirage; it was a nation’s mission. The settlers knew that someday democracy would be our rule. It would not be a tool to be used against us. Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness are the principles we endorse or did we? Through our actions we will see, whether these values are for you or me. For now, much seems lost.

There is No work. No funds for food. No hope, nor a hug. Congress excoriates. The wealthy bloviate. And those who work on the line, people who are but a blink from the brink, are happy to remain blind, oblivious to the veracity that could me.

Might we ask ourselves, is it our pride, or our prejudice, or perhaps our perceptions. Common Core. Is it more? Might it be you and me, and the children make three…

References and Resources…

- The Trouble with the Common Core. By the Editors of Rethinking Schools. Rethinking Schools. Summer 2013

- The conservative battle over Common Core Standards By Celia R. Baker. Deseret News National Edition. January 2, 2014

- Rand Paul Couldn’t Be More Wrong About Unemployment Insurance. By Matthew O’Brien. The Atlantic. December 9, 2013

- Washington Cares More About Deficits Than the Long-Term Unemployed: That’s Crazy. By Matthew O’Brien. The Atlantic. December 11, 2013

- Identity and Belonging. National Council for Curriculum and Assessment. 2012

- http://www.nber.org/papers/w17104>

Children Left Behind: The Effects of Statewide Job Loss on Student Achievement. By Elizabeth Oltmans Ananat, Anna Gassman-Pines, Dania V. Francis, Christina M. Gibson-Davis. National Bureau of Economic Research. Working Paper No. 17104 - Is the Economy Hurting Your Kid’s Report Card? By Stephen Gandel TIME Business. June 6, 2006

- “Man’s Search for Meaning: The Case of Legos.” By Dan Ariely, Emir Kamenica and Drazen Prelec Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization. Vol. 67: 671-677. 2008

- Doing Good or Doing Well? Image Motivation and Monetary Incentives in Behaving Prosocially. By Dan Ariely, Anat Brach and Stephen Meier (Forthcoming). American Economic Review. August 27, 2007

- Parents Depressions and Stress oleave Last Mark on children. By. Daily Beast. September 12, 2011

- Short-run Effects of Parental Job Loss on Children’s Academic Achievement. By Ann Huff Stevens and Jessamyn Schaller. National Bureau of Economic Research. November 2009

Unemployment from a Child’s Perspective

INTRODUCTION

When a parent loses a job, the entire family is affected, including the children. Money is suddenly tighter, and what was affordable last month, no longer is. Even children who are too young to be aware of financial adjustments may pick up on a change in the family atmosphere. Adults may be arguing more frequently, and parents may speak more sharply to their children. While children may benefit from their parents spending more time at home, the downsides of parental unemployment—the loss in family income and increase in parental stress—tend to overshadow such potential benefits, leaving children worse off when one of their parents loses a job.

Millions of American lost their jobs during the Great Recession, and millions were still unemployed in 2012. As a result, millions of children have experienced parental unemployment recently; 6.2 million children still lived in families with unemployed parents in an average month of 2012. The number rises higher—to 12.1 million, or one in six children—under broader measures of parental under- or unemployment. Because children are often overlooked in official unemployment statistics, this brief examines unemployment from a child’s perspective. It addresses the following questions:

- How many children are affected by parental unemployment?

- How does parental job loss affect children?

- Who are the children of the unemployed?

- Where do the children of the unemployed live?

- To what extent are families with children covered by unemployment insurance?

The brief concludes with a review of policies affecting the safety net for children of the unemployed. It is part of a series of issue briefs examining the impact of the recession on children. 1

HOW MANY CHILDREN ARE AFFECTED BY PARENTAL UNEMPLOYMENT?

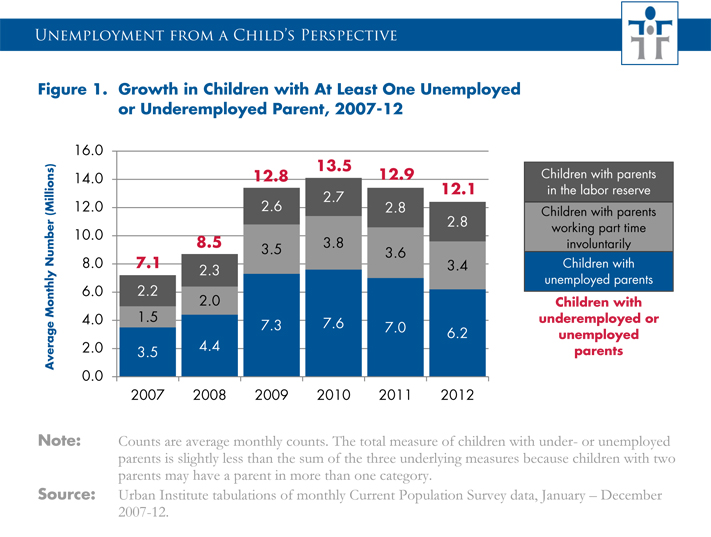

More than one in six children, or 12.1 million, were affected by parental unemployment and underemployment in 2012, under a broad measure that counts not only children with at least one

unemployed parent (6.2 million children) but also children living with at least one parent who had to settle for part-time work because of slack business conditions or difficulty finding full-time work (3.4 million) and children living with at least one parent who wants a job but is not actively seeking work and is classified by the Bureau of Labor Statistics as being in the labor reserve (2.8 million).2

As shown in figure 1, each of these measures of unemployment grew substantially between 2007 and 2010, with only modest improvement since the peak of the recession. For example, the average monthly number of children with at least one unemployed parent more than doubled between 2007 and 2010 (from 3.5 to 7.6 million); while it has declined since then, it is still much higher than before the recession (6.2 versus 3.5 million). The recession also has led to a substantial increase in parents who are working part time, involuntarily, for economic reasons. Compared to before the recession, more than twice as many children in 2012 are living with parents who would prefer to clock a full 40-hour workweek but have seen their hours cut or can’t find full-time jobs and must work part time instead (3.4 vs. 1.5 million). The recession has had less of an impact on the number of children with parents who want a job but are no longer actively seeking work, although this group of parents has continued to grow (from 2.2 million in 2007 to 2.7 million in 2010 and 2.8 million in 2012).

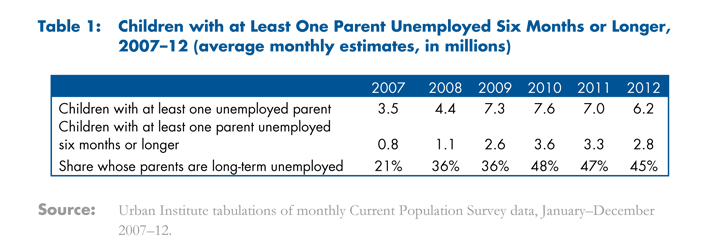

Of particular concern has been the dramatic growth in unemployment spells that last six months or longer. As shown in table 1, the number of children living with a parent who has been looking for work for six months or longer has more than tripled, from 0.8 million in 2007 to 2.8 million in 2012. This represents almost half (45 percent) of all children living with unemployed parents. Families with such long periods of unemployment have much higher risks of poverty and financial hardship than families where the unemployed parent finds another job more quickly.

While most of this brief focuses on children living with unemployed parents, youth unemployment has also risen sharply during the recession. The number of unemployed youth age 16 to 24 rose from 2.6 million in July 2007 to 4.4 million in July 2009 and 2010, before dropping slightly to 4.0 million in July 2012. This past July, the unemployment rate for 16- to 24-year-olds was 17.1 percent, below the 19.1 percent rate of July 2010 but still far above the 10.8 percent rate back in 2007.

HOW DOES PARENTAL JOB LOSS AFFECT CHILDREN?

One of the first impacts of parental job loss is that families have fewer financial resources available to meet their regular monthly expenses and support their children’s development. Reductions in family income are more likely to threaten children’s development if the family’s income falls below the poverty level, as may occur if income was low before the job loss, the unemployed parent is the sole breadwinner, or the spell of unemployment lasts for many months.

In their analysis of family income and poverty after unemployment, Zedlewski and Nichols (2012) report that poverty nearly triples among parents who remain out of work for six months or longer, even after counting the value of benefits from safety net programs. Specifically, the poverty rate for long-term unemployed parents, who represented 45 percent of the authors’ sample, rose from 12 percent before the job loss to 35 percent during their period of unemployment.3 Children in poverty may lack the resources that support healthy development if the family has trouble providing nutritious meals, safe child care settings, access to learning materials, and other resources that promote healthy development or if the family moves into crowded housing or neighborhoods with more crime and air and noise pollution.4 As a result, living in poverty can have detrimental effects on children’s long-term well-being, particularly if children live in poverty while young or for prolonged periods.5

Job loss also can have a negative impact on family dynamics. A body of research dating back to the Great Depression finds evidence of increased parental irritability and depression and higher levels of family conflict after parental job loss, with spillovers into less supportive and more punitive parenting behaviors. Developmental psychologists emphasize the links between economic stress and parents’ mental health, and further links to parents’ responses to their children and children’s well-being.6 Finally, in addition to lower financial resources and changes in family processes, parental job loss may lead to changes in adolescents’ attitudes toward work, as they see their parents’ lack of success in the labor market.

One of the earliest signs that children are not doing well is their school performance. Several studies have documented lower math scores, poorer school attendance, and a higher risk of grade repetition or even suspension or expulsion among children whose parents have lost their jobs.7 For example, Stevens and Schaller (2011) find that parental job loss increases the chances a child will be held back in school by nearly 1 percentage point a year, or 15 percent.

Not all families are affected equally. Some studies find differences between paternal and maternal job loss, with larger negative effects on both family conflict and child outcomes when the father rather than the mother loses the job.8 Other studies find larger effects among families with less income, suggesting that poverty and economic hardship after job loss may explain some of the negative effects. 9

The adverse effects of parental job loss can persist into a child’s adult life. For example, Coelli (2010) reports that low-income youth whose parents lose their jobs have lower rates of college attendance. Moreover, Oreopoulos, Page, and Stevens (2008) find that boys whose fathers lost their jobs when plants closed in the early 1980s had annual earnings about 9 percent lower than similar children whose fathers did not experience such job losses.10 Such long-term effects may result from a combination of reduced family income at critical times (such as when the youth is making plans for postsecondary education), the detrimental effects of family conflict and harsh discipline behaviors, and changes in the child’s aspirations for success in the labor market.

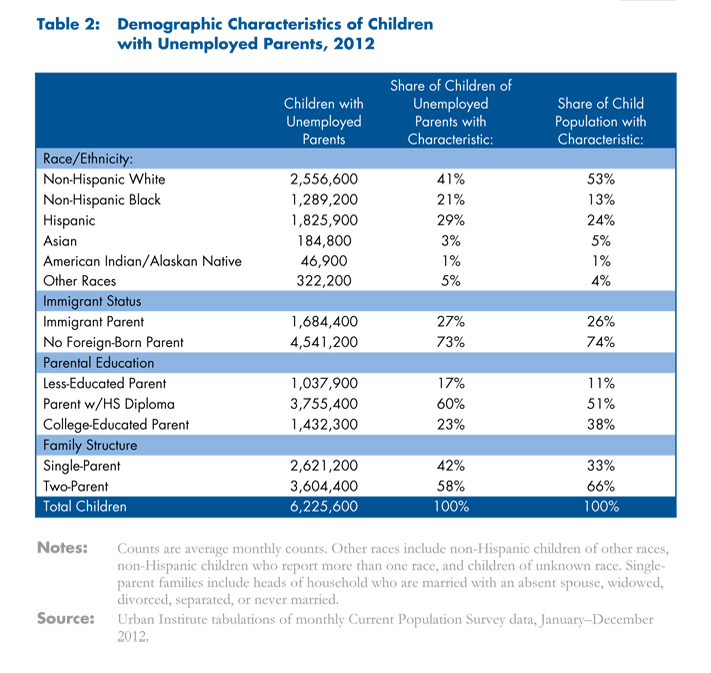

WHO ARE THE CHILDREN OF THE UNEMPLOYED?

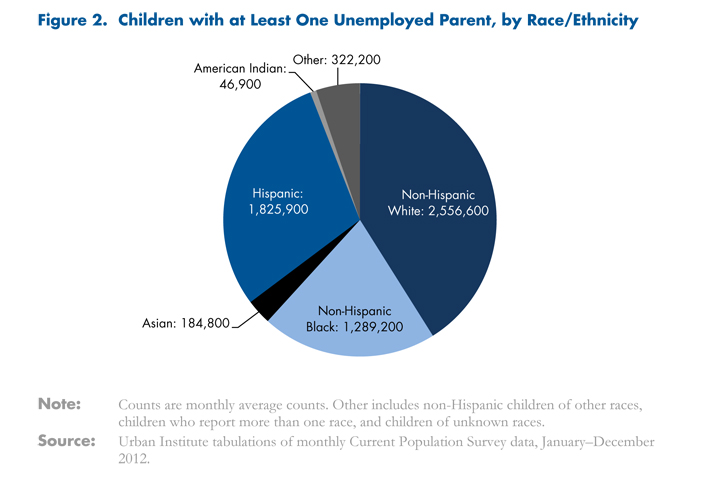

Children affected by parental unemployment come from diverse family backgrounds. Of the 6.2 million children living with unemployed parents in an average month of 2012, 2.6 million are non-Hispanic white, 1.3 million are non-Hispanic black, 1.8 million are Hispanic, 185,000 are Asian, 47,000 are American Indians and Alaskan natives, and 322,000 are children of other races, including children of more than one race (figure 2). About a quarter of children of the unemployed are children of immigrants, similar to the percentage of children of immigrants among the general population (see table 2). Slightly less than one-fifth are children whose parents lack high school diplomas, three-fifths are children of high school graduates, and nearly one- quarter are children of college-educated parents. Finally, two-fifths are children in single-parent families, and three-fifths are children in two-parent families.11

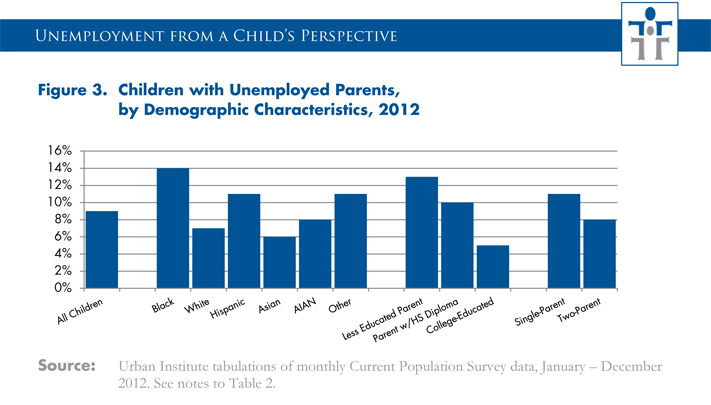

While children of the unemployed include children of varied family backgrounds, some demographic groups are more heavily represented than others. Black children are twice as likely to live with unemployed parents as white children (14 percent versus 7 percent), as shown in figure 3. Children of college-educated parents are less likely to be affected by unemployment than other children (5 percent for college-educated parents versus 10 percent for high school graduates and 13 percent for parents without high school diplomas). And, children in single-parent families are more likely to live with an unemployed parent than children in two-parent families (11 percent compared with 8 percent).

In their research on unemployed parents, Zedlewski and Nichols (2012) find similar patterns by demographic characteristics. However, their research shows interesting patterns regarding length of unemployment spells. While parents without high school education and Hispanic parents experience unemployment more often than parents in other education and racial/ethnic groups, they tend to be out of work for shorter periods than other unemployed parents.12

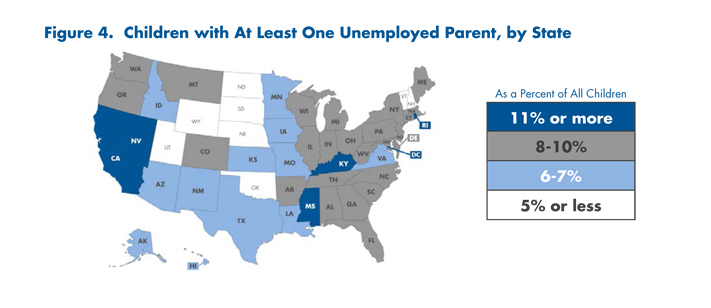

WHERE DO CHILDREN OF THE UNEMPLOYED LIVE?

Children with unemployed parents live throughout the country. According to the most recent data, nearly 1 million (976,000) of them live in California, reflecting both the size of the state’s population and the severity of its economic problems. More than one in ten children in California (11 percent) live with at least one unemployed parent. Nationwide, an average of 9 percent of children live with at least one unemployed parent, with the percentage ranging from under 4 percent in North Dakota and Vermont to 13 percent in the District of Columbia and Rhode Island, as shown in figure 4, below, and appendix table A-1.13

While the depth of the problem varies across states, all states saw a sharp rise between 2007 and 2009 in the number of children living with at least one unemployed parent. In most states, the numbers have remained persistently high since then. The 2012 data show more children living with unemployed parents today than before the recession started in all but two states. (The two exceptions are North Dakota and Vermont, already flagged above as having very low shares of their child population in families with unemployed parents.) In fact, 12 states have more than twice as many children with unemployed parents than they did five years ago: Alabama, Delaware, Florida, Hawaii, Idaho, Indiana, Maryland, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania (these states have 2007–12 growth rates of 100 percent or more, as shown in appendix table A-1).

Further measures of unemployment by state and in large metropolitan areas are provided in the appendix tables. For example, the number of children affected by parental unemployment or underemployment in California rises to more than 1.9 million, or 22 percent of the state’s child population, when considering children with at least one unemployed parent along with children whose parents are working part-time involuntarily or have dropped out of the labor force but say they want to work (see appendix table A-2). Children living with parents out of work for more than six months are a particularly large share (50 percent or more) of children of the unemployed in Connecticut, the District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina and South Carolina (see appendix table A-3).

Statistics by large metropolitan area indicate that one-fifth (20 percent) of the children in the Modesto, California, metropolitan area are living with at least one unemployed parent, with unusually high percentages also found in Bakersfield, California (17 percent), Riverside-San Bernardino-Ontario, California (16 percent), and Toledo, Ohio (15 percent) (see appendix table A-4).

Leave A Comment