By Emily Richmond | Originally Published at Education Writers Association. February 26, 2014

When it comes to having their voices heard, teachers overwhelmingly say they aren’t being listened to on matters of education policy at the state or national level.

At the school level, however, 69 percent of teachers said their opinions carried weight, according to the third edition of the “Primary Sources” survey by Scholastic and The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which was published Tuesday.

That figure dropped dramatically as the size of the sphere increased. Only one in 20 teachers said they were being heard statewide, and one in 50 teachers felt they had a voice nationally. It would be tough to find a profession facing greater scrutiny by policymakers at every level than what teachers currently experience, which makes it notable that so many of them perceive themselves as not being heard at the levels where most of the major policy decisions are made.

Before we dig into the results, a couple of points to consider. First off, the report is based on a remarkable amount of input, given that more than 20,000 teachers shared their opinions both online and through in-person interviews. At the same time, it’s important to remember that a survey is a snapshot, not a definitive litmus test. As I’ve previously argued, it’s wise to proceed with caution in interpreting the findings.

Teachers overwhelmingly said they joined the profession to make a difference in the lives of children, with 85 percent of those surveyed listing it as one of the reasons. Only 14 percent cited having summer off from work as a reason, and 4 percent chose earning potential as a factor. When asked if the rewards of their profession outweighed the challenges, 46 percent of teachers said they “agree strongly” while 42 percent “agree somewhat.” Only 12 percent disagree. (For more on surveys measuring teacher job satisfaction, and why that’s a tricky question to ask or answer, go here.)

Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, said in a statement about the survey that confirms “that teachers go into this work to make a difference in the lives of children, but they want to have a real voice and the collaboration they need to do that work … The bottom line: Teachers are overwhelmingly respected and valued by parents and their communities, and it’s long past time for policymakers to listen to what teachers say they need to help children succeed.”

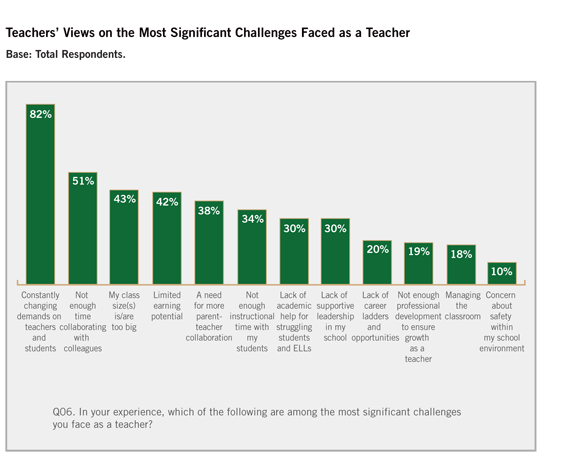

If you want to know what teachers are worried about, consider the chart below ranking a list of professional challenges. “Constantly changing demands on teachers and students” was the most common response at 82 percent, which shouldn’t be ignored by policymakers and school leaders eager to add yet another program or initiative. Not having enough time to collaborate with colleagues was a distant second at 51 percent, followed by overly large class sizes (43 percent) and limited earning potential (42 percent). School safety concerns took the last spot with 10 percent.

To be sure, it’s been a tumultuous time to be an educator. There was a 12-year stretch of new federal edicts that came with No Child Left Behind, as well as President Obama’s school reform initiatives, particularly Race To The Top and the School Improvement Grant program. Along with those new mandates came a host of new instructional approaches, grading systems, and teaching materials. Frequent changes in school leadership also take a toll. As one middle school teacher put it in the Gates survey, “We have a new principal almost every two to three years, and that changes everything all over again.” And there is certainly more change on the horizon, particularly with the rollout of the Common Core, and no shortage of new ideas about how to improve instruction and student learning.

The full report is worth a careful read, but here are a handful of takeaways:

That’s consistent with a survey of state-level education officials by the Center on Education Policy, which found a similar level of support for the new standards, and concerns about whether schools would have the necessary tools for successful implementation.

Diane Rentner, deputy director of CEP, told me that the Scholastic/Gates survey “gives us some really good information about what the teachers are thinking about the Common Core, and they’re the ones who are ultimately going to make it happen.”

Rentner pointed out that while teachers became more confident about the usefulness of the Common Core as their familiarity with the new standards increased, it didn’t change their belief that the implementation would be challenging.

“They believe it will help students but they also realize this won’t be a cakewalk,” Rentner said. “It’s good to see that acknowledged, that it’s going to take hard work and fundamental changes.”

In recent months there have been reports of teacher groups pushing back against Common Core, notably in New York City. But having concerns about how new Common Core-aligned assessments will be used to measure teacher job performance or expressing concern about the rollout is different from disagreeing with the need for revamped grade-level expectations, Rentner said. (Politico’s Stephanie Simon contended last week that teacher support for the Common Core is at a “critical juncture,” noting that National Education Association President Dennis Van Roekel had called the implementation “completely botched.”)

The strong teacher support for the Common Core revealed by the survey is “a powerful message,” said Andy Smarick, a senior policy fellow with the conservative Thomas B. Fordham Institute in Washington, D.C. and a partner at Bellwether Education Partners. He was also encouraged that teachers believe the Common Core will help improve math instruction – a key goal of the new standards.

But Smarick questioned whether teacher evaluations (a framework which has expanded at an exponential rate nationally over the past four years) are on the right track, given that only a relatively small percentage of teachers found them to be “extremely” or “very” helpful. At the same time, Smarick said, it’s “fascinating that teaches frustrated with their evaluations want more feedback and better observers.”

Clearly, the report is loaded with thought-provoking data: from the online resources teachers using most often in the classroom (YouTube finished first) to how their perceptions vary by geographic region, level of experience, and the demographics of their schools. And it’s a perspective that’s too often a rarity in the wider debate over school improvement, student achievement, and the teacher workforce. As Rentner, deputy director of the CEP put it: “It’s refreshing to hear from the real people actually doing the job, don’t you think?”

Have a question, comment or concern for the Educated Reporter? Email Emily Richmond. Follow her on Twitter: @EWAEmily.

Leave A Comment