Photograph; Roland Park Fourth-graders do classwork in their homeroom at Roland Park Elementary/Middle School in Baltimore. The school is the most racially diverse school in the most segregated school district in the state. (Kim Hairston, Baltimore Sun /May 7, 2014)

As accounts and the report 'Settle for Segregation or Strive for Diversity? A Defining Moment for Maryland’s Public Schools' reveal everyday people and 'Educators continually claim that they know how to make schools segregated by race and poverty equal. The statistics across the nation show that, with very few exceptions, that is not true….After the Supreme Court declared mandatory segregation by state law unconstitutional in l954, desegregation was expected to be a less difficult in 'Border states' (such as Maryland) and it clearly was in the early stages. But then Maryland fell seriously behind much of the South and became one of the nation’s most segregated states for black students.'

60 Years After Brown v. Board of Ed, Pockets of Segregation Remain in Md. Schools

At 16, Dorant Wells has experienced the complexities of what Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark school desegregation ruling, has wrought: He attended a middle school full of students of different colors and nationalities, but one where he sometimes felt there were lower expectations for black students.

Now at his nearly all African-American high school, Milford Mill Academy in Baltimore County, he sees value in the special character of the school, while acknowledging he may be less prepared to enter a diverse world. “It keeps us united. We may not agree on everything, but we have each other,” said Dorant.

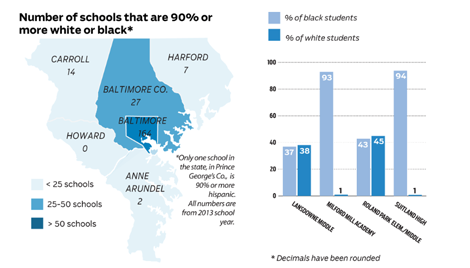

Sixty years after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that racial segregation in 21 states was unconstitutional, diversity is not guaranteed in Maryland’s schools. Ten percent of the schools in Maryland have a high percentage of black students, nearly all of them in Baltimore City and Prince George’s County, according to a Baltimore Sun analysis. And no political or education leaders are recommending a consolidation of suburban and urban districts that experts say would be needed to truly address an imbalance driven largely by neighborhood demographics.

Instead, the struggle for racial integration and educational equality is taking place in the suburbs, where students are learning in increasingly diverse schools.

Read Civil Rights Project Report; Settle for Segregation or Strive for Diversity? A Defining Moment for Maryland’s Public Schools.

Students in these more integrated middle and high schools say they relish the multicultural environments. And while they say there are still daily struggles over issues of race and diversity, such conflicts have made them stronger, more resilient and more socially adept.

“I take diversity very seriously,” said Destiny Battle, an African-American eighth-grader at Lansdowne Middle, one of the most diverse schools in Baltimore County. “I like the different races in the classes.”

Students learn, the 14-year-old said, that no race is better than another. In her classes she hears viewpoints that are far different from her own and that sometimes make her reconsider the norms in her own culture.

Outside Baltimore City and Prince George’s County, only three districts have any schools with a black population higher than 75 percent, The Sun’s analysis showed. In Baltimore County, about 16 percent of the schools are over that level. In Anne Arundel County, it is 1 percent.

There are no schools in Howard, Harford or Carroll counties with a black enrollment as high as 75 percent, but together those districts have nearly 75 schools that are more than 90 percent white. Anne Arundel has 41 nearly all-white schools; Baltimore County has 23.

The state has two schools — Suitland High in Prince George’s and Milford Mill — that are considered “apartheid” schools by the Civil Rights Project because they have a white population of less than 1 percent.

Lansdowne Middle

Kelvin Interiano (clockwise from back left), Hope Gardner, Mahmud Cole and Destiny Battle attend the diverse Lansdowne Middle School in Baltimore County.”I take diversity very seriously,” said Destiny. “I like the different races in the classes. | | Barbara Haddock Taylor, Baltimore Sun / May 7, 2014a

Middle-class black families benefited most from the Brown ruling because it gave them the opportunity to move to white neighborhoods and put their children in better schools, said Baum, a professor in the urban studies and planning program at the University of Maryland, College Park.

The black migration out of the city’s Liberty Road corridor now means that some area schools lack racial diversity. For example, enrollment at Milford Mill Academy, which is off Liberty just outside the Baltimore Beltway, is 93 percent African-American. Although the school has nine magnet programs designed to attract top students from around the county, most of those coming to the school are students of color.

Though their school is often viewed as low-achieving, students get into top universities such as Stanford and Yale, said Principal Roderick Harden. A number of top students said they would not change the racial makeup of their school. Jazzlyn Briscoe, 17, said she recognizes that diversity would foster tolerance, but she also said it is easier to be in a predominantly African-American environment.

She recalled a time when she experienced racism outside of school, when someone said: “I wasn’t expecting you to be as articulate as you are.”

Dipo Adeuyan, 17, likes the school the way it is but recognizes the limitations. “I believe it could hinder me. You have to create healthy relationships” with people of other races, he said. For that reason, he said he might be more likely to attend a majority white college or university.

Harden and his students pointed out that there is a great deal of socioeconomic and cultural diversity within the school. He said his students come from “$500,000 homes and group homes” and while they may all be students of color, they come from Jamaica and Africa and many other backgrounds that fill the school with different perspectives.

Baltimore County schools Superintendent Dallas Dance “is not worried” about the predominantly African-American schools in his system. “You look at Randallstown

As important as racial balance is, the quality of a school is more often determined by the percentage of students in poverty, and the access students have to good teachers, experts say. Other states have tried to increase achievement by attracting both white and higher-income families to high-poverty schools.

Dance said he wants all students across the county to have equal access to high-quality teachers and to face high academic expectations. While he believes the county has made progress, he says students in higher-poverty schools have been given lower expectations than those in wealthier areas.

Dance said the district is working on an equity policy to ensure opportunity and access throughout the county.

One of his greatest challenges, Harden said, is fighting the stereotype that students have of themselves as low achievers.

In more diverse schools, there’s a much greater culture of competition and less likelihood of having to fight that stereotype, said Mahmud Cole, an eighth-grader who went from Woodlawn Middle to more diverse Lansdowne Middle, where he said he is much happier and finds it easier to succeed.

Mahmud, whose mother is from West Africa, said socioeconomic status is as important as race. He said he believes race is barely an issue at school. But students at diverse schools described an environment that often overturns all the stereotypes about race. At Lansdowne, students acknowledged that the top achievers are usually black.

In every school where teenagers were interviewed, they said the cliques and groups that develop — the geeks, the athletes, and so on — are sometimes more powerful forces than race or income.

They see culture and race far differently than their parents and teachers, and are more comfortable explaining the nuances and the contradictions. They say their school environments allow them to work out many of the issues of race they will confront them later in the larger society — even when those issues are complicated.

“It is definitely a situation where kids view it differently than the adults,” Dance said.

While black and white students easily mix at Lansdowne’s cafeteria tables, the Hispanic kids sit off to the side at their own table. And there are still skin color distinctions. Hope Gardner, 14, who is white, has made friends with a boy from Africa who she said is teased because of his dark skin.

At Roland Park Elementary/Middle in Baltimore, the most racially diverse school in the most segregated school district in the state, a biracial girl, Destiny Brown, doesn’t have to decide whether black or white is “cool” enough to impress her peers. But she did have to straighten her hair to stave off unwanted petting of her curls in the lunch line.

Roland Park school leaders say a community buy-in to a strong public school option has helped it achieve diversity — from affluent residents who choose not to send their kids to private schools to less-affluent parents who move to apartments just to be zoned there.

Adam Kelley, an eighth-grader at Roland Park who lives on a predominantly white street in the neighborhood, said he was glad his parents chose not to send him to a private school where most students look like him.

“Because I grew up in this school … I feel like I’m a lot more prepared for life than [private school students] are,” he said. “I’m taught with people that I’ll grow up with and live with and have to deal with.”

The Ingenuity program was Destiny Brown’s way into a more rigorous school — and out of the “white girl” box she felt confined to at her predominantly black elementary school.

“It was a lot of me trying to impress people and trying to show that I’m cool even though I’m half-white,” she said. “It doesn’t really come up here.”

But with greater diversity comes greater responsibility, said Nicholas D’Ambrosio, principal of Roland Park.

“I can say with confidence that our kids really appreciate each other,” D’Ambrosio said. “But with all of our great successes, we also have challenges, especially around race. We want to make sure we’re being reflective of ourselves and creating an environment that’s welcoming and meeting the needs of all students, all families.”

Milford Mill

Darin Dabney, 17, a senior at Milford Mill Academy, talks about attending a school with a predominantly African-American student body. The state has two schools –Milford Mill in Baltimore County and Suitland High in Prince George’s — that are considered “apartheid” schools by the Civil Rights Project because they have a white population of less than 1 percent. | Kim Hairston, Baltimore Sun / May 7, 2014

The high-performing school ranks among the best in the state, but achievement gaps persist. The program for its highly gifted students, Ingenuity, is 65 percent white. Its parent base is an integral part of the school, but participation by minority parents is sparse.

Still, parents say that their children are thriving at Roland Park, and what has made them more comfortable with the school is its willingness to tackle race and cultural issues head-on.

“I think the adults are aware that we could be doing certain things better,” said Arnetta M.R. Young, the mother of an African-American sixth-grader who transferred from a private school. “Race is not easy to talk about … but if we have those hard conversations, there’s room for tremendous growth.”

Roland Park also promotes its diversity. For example, it encourages staff and parents to undergo cultural proficiency training and asks job candidates about ways they’ve dealt with different kinds of cultures and students. In addition, the school confronted themes of race and discrimination when it put on a production this spring of the musical “Hairspray.”

Nicholas Prosper, an eighth-grader, said that when he recited the line, “Not bad for a white girl” about the main character’s dance moves, he learned about reverse racism.

“I used to think it was just whites who would be discriminative toward blacks,” Nicholas said.

The lack of diversity can be an issue at schools with a mostly white student body, like Hereford High in the northern part of the county. Like some students at Milford Mill, Nick Burton-Prateley, a 16-year-old Hereford sophomore, understands that his education is lacking something. Interacting with other races “is a skill of sorts you don’t get when you go to a school like Hereford.”

Sometimes he notices the lack of diversity. “It is a wake-up call to see that there is still this segregation in schools. You are taught that it doesn’t exist anymore, but then you walk down the hall.”

Andrew Last, Hereford‘s principal, believes the 92 percent white student body is a function of the socioeconomics of the school’s boundaries, which covers large stretches of rural area and reaches to Pennsylvania.

“I love a mix,” said Last, a native of Britain. “America is a mixed culture, and that’s healthy. I always like different people in the building who offer viewpoints.”

He tries to find other opportunities for diversity, such as hosting foreign exchange students and hiring staff of color.

The widespread segregation that exists in Baltimore City and Prince George’s County — and in pockets of Baltimore County — is unlikely to change.

“Baltimore City has limited choices in what it can do to mix students by race and income,” Baum said. “It doesn’t have control over family choices about where to live.”

Baltimore County does use magnet schools as a way to give students choices for middle and high schools. And each year thousands of students leave their neighborhoods to attend a magnet program or school. Dance would also like to see students from mostly white Sparrows Point High and mostly black Woodlawn High get together more often for athletic events, chess tournaments and other extracurricular activities.

In 1996, Connecticut’s highest court ordered the legislature to find a way to integrate Hartford‘s schools across district lines, according to an Abell Foundation report suggesting such a model could be applied to Baltimore. The result in Hartford has been the establishment of more than 30 magnet schools that attract white, black and Latino students.

But without a major push for magnet schools, little is likely to change.

That leaves one big remaining question for city kids, said Baum, the author and professor.

“Is the city going to be able to help a predominantly poor student body succeed educationally, without being able to integrate schools economically?” he said. “We hope the answer is yes, but that will remain to be seen.”

Interactive designer Dana Amihere conducted data analysis for this article. Baltimore Sun researcher Paul McCardell contributed. liz.bowie@baltsun.com egreen@baltsun.com

Brown v. Board of Education

Decided on May 17, 1954, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kan., was a combination of five lawsuits challenging segregation from South Carolina, Delaware, Virginia, Washington, D.C., and Kansas.

The decision found that segregated schools violated the equal-protection clause of the 14th Amendment and that separate schools were inherently unequal and therefore unconstitutional.

Thurgood Marshall, an NAACP attorney who had been educated at Baltimore’s all-black Frederick Douglass High School, successfully argued the case before the Supreme Court. He was later appointed a justice.

Baltimore’s school board acted quickly that fall to offer choice to black and white families who wanted to move their children to other schools, while county schools remained segregated.

By 1961, Baltimore schools had changed from an overwhelmingly white enrollment to a mostly black population and still had many segregated schools.

Copyright © 2014, The Baltimore Sun

Leave A Comment