By Paul L. Thomas, Ed.D. | Published at The Becoming Radical. June 16, 2014

As a high school English teacher for nearly two decades, I came to embrace a need to offer students a wide range of lenses for interacting with and learning from many different texts, but I also learned that coming to read and re-read, to write and re-write the world is both a powerful and disorienting experience for young people. So a strategy I now use and encourage other teachers to implement is reading and discussing children’s literature, picture books, while expanding the critical lenses readers have in their toolbox.

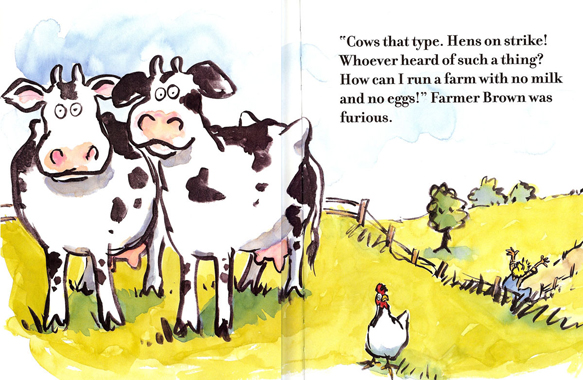

My favorite book for this activity is Click, Clack, Moo: Cows that Type. This work by Doreen Cronin with art by Betsy Lewin (view a read-aloud here) presents a clever and humorous narrative about Farmer Brown and his suddenly recalcitrant cows who, having acquired a rickety typewriter, establish a strike that inspires the chickens to join and ends with the neutral ducks aiding the revolt.

This story is ideal for asking teachers to consider the traditional approach to text in schools, New Criticism (a focus on text in isolation and on the craft in any story, such as characterization, plot, and theme), against Feminist and Marxist criticism, for example.

One fall, while doing the activity with a young adult literature class, I came against yet a new reading of Cronin and Lewin’s work: Why the 1% always wins.

The U.S. Public Likes Farmer Brown

As we explored Click, Clack, Moo recently, the adult members of the class told me they like Farmer Brown, with one student characterizing the striking farm animals as “mean.” And here is where I felt the need to consider how this children’s book helps us all confront the Occupy Wall Street movement or the rise in antagonism toward teachers, tenure, and unions as well as why the 1% continues to own the 99%.

One important element of the story is that the cows and chickens are female workers under the authority of the male Farmer Brown. These female workers produce for the farmer and remain compliant until the cows acquire the typewriter—both a powerful tool of literacy (the cows and chickens cannot effectively strike until they gain access to language) and a representation of access to technology (readers should note that the cows and chickens produce typewritten notes that show they find an old manual typewriter unlike the cleaner type produced by Farmer Brown on an electric typewriter, a representation of the inequity of access to technology among classes).

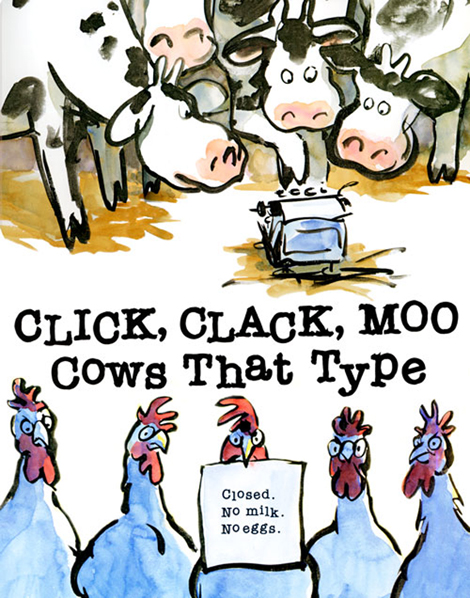

The cows and chickens, in effect, unionize and strike. Here, members of my classes often fail to notice the unionization, but tend to side with the farmer even when we acknowledge the protest as unionizing—particularly bristling at the duck, as a neutral party, using its access to the negotiation to acquire a diving board for the duck pond.

Like the 1%, Farmer Brown is incensed that the cows and chickens demand basic necessities for comfort, electric blankets, but he eventually secures a compromise, agreeing to give the barn animals the requested electric blankets for the return of the typewriter (the story ends with the obvious next step that the duck uses the typewriter to trade for the diving board).

What tends to be missed in this story is that Farmer Brown ultimately wins; in fact, the barn animals appear to be eager to abandon their one access to power, the typewriter, for mere material items—the electric blankets as comfort many would see as a basic right and the diving board as frivolous entertainment.

The 1% have the 99% right where Farmer Brown has the barn animals—mesmerized by the pursuit of materialism and entertainment. Consider the eager hordes of consumers lined up to buy the then-new iPhone 4S, released on the cusp of the passing of Steve Jobs, heralded as a genius for his contribution to our consumer culture.

Just give us our iPhones and we’ll be quiet, we’ll work longer and harder for the opportunity to buy what the 1% tells us we want.

And when the 1% and their compliant media inform us that the top 20% pays 64% of taxes, we slip back to our barns with our tails between our legs, shamed.

Instead, we should be noting that, yes, the top 20% income earners pay 64% of taxes because they make 59% of income.

We, the 99% who tend to remain silent and compliant, wait patiently for the next generation of technology to occupy our time, our lives reduced to work and amassing the ever-changing and out-dated things that become passé as the next-thing lures us further and further into our sheep lives.

Yes, if we remain eager to trade our voices for things, the 1% will always be the winners.

When we learn to treasure voice over things, however, the chickens may come home to roost.

Leave A Comment