Tammie Hagen-Noey, in her bedroom at a group home in Richmond, Va., earns $7.25 an hour at a local McDonald’s. |Credit; Drew Angerer for The New York Times

Changed Life of the Poor: Better Off, but Far Behind

WASHINGTON — Is a family with a car in the driveway, a flat-screen television and a computer with an Internet connection poor?

Americans — even many of the poorest — enjoy a level of material abundance unthinkable just a generation or two ago. That indisputable economic fact has become a subject of bitter political debate this year, half a century after President Lyndon B. Johnson declared a war on poverty.

Starkly different views on poverty and inequality rose to the fore again on Wednesday as Democrats in the Senate were unable to muster the supermajority of 60 votes needed to overcome a Republican filibuster of a proposal to raise the incomes of the working poor by lifting the national minimum wage to $10.10 an hour.

House Republicans, led by Representative Paul D. Ryan of Wisconsin, have convened a series of hearings on poverty, including one on Wednesday, in some cases arguing that hundreds of billions of dollars of government spending a year may have made poverty easier or more comfortable but has done little to significantly limit its reach.

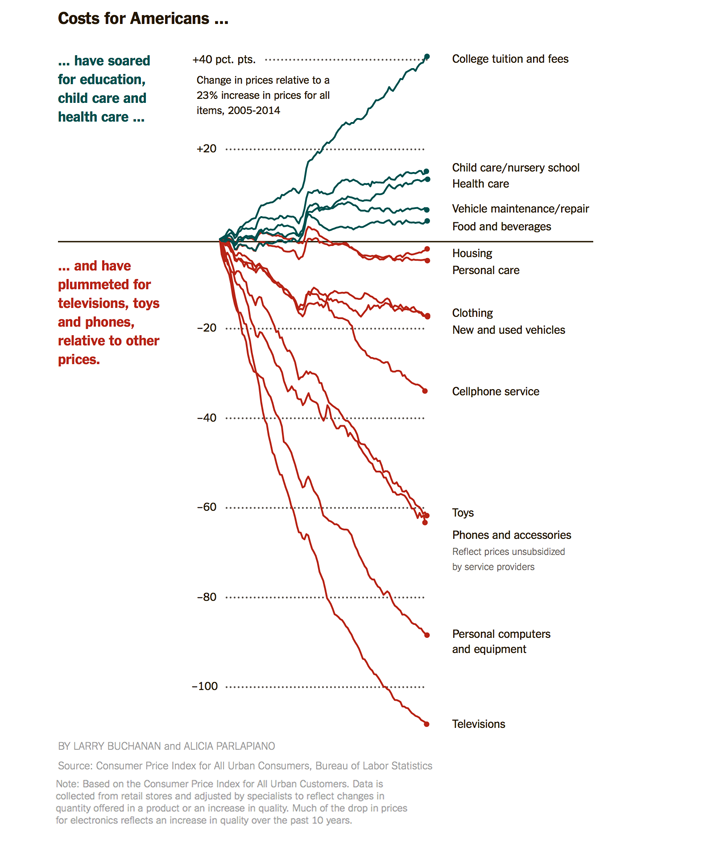

Indeed, despite improved living standards, the poor have fallen further behind the middle class and the affluent in both income and consumption. The same global economic trends that have helped drive down the price of most goods also have limited the well-paying industrial jobs once available to a huge swath of working Americans. And the cost of many services crucial to escaping poverty — including education, health care and child care — has soared.

“Without a doubt, the poor are far better off than they were at the dawn of the War on Poverty,” said James Ziliak, director of the University of Kentucky’s Center for Poverty Research. “But they have also drifted further away.”

Democrats have generally argued that addressing this disjunction requires providing more support for the poor, raising the minimum wage, extending unemployment insurance benefits and making health care more affordable by expanding the reach of Medicaid and subsidizing private insurance for those who lack employer coverage.

Republicans, by contrast, have proposed reducing government regulations and overhauling existing programs to encourage more work, arguing that would allow Washington to decrease spending on the poor.

“The question isn’t whether the federal government should help; the question is how,” Mr. Ryan said at the hearing on Wednesday. “How do we make sure that every single taxpayer dollar we spend to reduce poverty is actually working?”

For many working poor families, the most apt description of their finances and lifestyle might be fragile. Even with a steady paycheck, keeping the bills paid becomes a high-wire act and saving an impossibility.

Tammie Hagen-Noey, a 49-year-old living in Richmond, Va., tapped at an iPhone as she sat on the porch of the group home where she lives — its proprietor is a friend of her daughter’s. She earns $7.25 an hour at a local McDonald’s, and makes a little extra money on the side from planting small plots of land for neighbors who want to garden.

Ms. Hagen-Noey is trying to rebuild her finances, which have been decimated by divorce, government liens and addiction. At the top of her list of priorities is finding better-paid work. She produced a paycheck that showed her earnings so far this year: $2,938.51.

“It’s impossible,” she said. “Every cent of that goes towards what I need.” A few months ago, she sold her car for $500 to make rent.

Two broad trends account for much of the change in poor families’ consumption over the past generation: federal programs and falling prices.

Since the 1960s, both Republican and Democratic administrations have expanded programs like food stamps and the earned-income tax credit. In 1967, government programs reduced one major poverty rate by about 1 percentage point. In 2012, they reduced the rate by nearly 13 percentage points.

As a result, the differences in what poor and middle-class families consume on a day-to-day basis are much smaller than the differences in what they earn.

“There’s just a whole lot more assistance per low-income person than there ever has been,” said Robert Rector, a senior research fellow at the conservative Heritage Foundation. “That is propping up the living standards to a considerable degree,” he said, citing a number of statistics on housing, nutrition and other categories.

Decades of economic growth, however, have been less successful in raising the incomes from work of many poor families, prompting a strong conservative critique this year that hundreds of billions of dollars in antipoverty programs have failed to make the poor less dependent on government.

PLAY VIDEO|1:22

Times Minute | Minimum Wage Politics

Today on the Minute, the minimum wage is at the heart of debate between Democrats and Republicans. | Video Credit By Mona El-Naggar on May 1, 2014. | Image Credit: Alex Wong/Getty Images

“That’s the crux of the problem,” Mr. Rector added. “What sort of progress is that?”

But another form of progress has led to what some economists call the “Walmart effect”: falling prices for a huge array of manufactured goods.

Since the 1980s, for instance, the real price of a midrange color television has plummeted about tenfold, and televisions today are crisper, bigger, lighter and often Internet-connected. Similarly, the effective price of clothing, bicycles, small appliances, processed foods — virtually anything produced in a factory — has followed a downward trajectory. The result is that Americans can buy much more stuff at bargain prices.

Many crucial services, though, remain out of reach for poor families. The costs of a college education and health care have soared. Ms. Hagen-Noey, for instance, does not treat her hepatitis and other medical problems, as she does not qualify for Medicaid and cannot pay for her own insurance or care.

Child care also remains only a small sliver of the consumption of poor families because it is simply too expensive. In many cases, it depresses the earnings of women who have no choice but to give up hours working to stay at home.

“The average annual cost for infant care in the U.S. is $6,000 or $7,000 a year,” said Professor Ziliak of the University of Kentucky. “When you look at the average income of many single mothers, that is going to end up being a quarter of it. That’s huge. That is just out of reach for many folks.”

Tiffany Beroid, a 29-year-old mother who works at a Walmart in Laurel, Md., said she works part time, rather than full time, because she and her husband could not otherwise afford child care. Their incomes already suffered when her doctors told her to stay off her feet during the late stages of her pregnancy, and she said Walmart would not accommodate her with a desk job.

“Child care was costing probably $350 a week,” said Ms. Beroid, who makes $10.70 an hour. “I would love to be in full-time work, if I could make enough to cover child care payments.”

And many poor families barely make it from paycheck to paycheck. For evidence, economists point to the fact that children living in families with food stamps eat more calories at the beginning of the month than the end of it.

Economists pointed out that many low-income families struggled to use even the assets they had: keeping gas in the car, paying for cable and keeping the electricity on. Many families rely on expensive credit. And even if those families sold their assets, often it would only provide them with a small buffer, too.

Anthony Goytia, who works the night shift at a Walmart in Southern California, is reliant on payday loans to pay his bills.

“Some of our bills come in at the middle of the month,” said Mr. Goytia, a father of four who makes about $16,000 a year. “Then we’ve got to pay our rent by the first, and when we don’t have the money, we have to take out a payday loan.”

Bobby Bingham, 38, of Kansas City, Mo., works three part-time jobs seven days a week to make ends meet, but struggles to cover basic living expenses: his apartment, his car, his car insurance, gas and utilities. He is also heavily in debt, owing $30,000 in student loans and about $12,000 in credit-card debt with an annual interest rate of 17 percent.

“It’s hard on my psyche,” he said. “There’s no break. There’s no time to breathe. I always have to think about the next step just to survive. It’s not like I can look forward and plan, because I’m just trying to think about tomorrow.”

In the end, many mainstream economists argue, the lives of the poor must be looked at in light of the nation’s overall wealth and economic advancement.

“If you handpick services and goods where there has been dramatic technological progress, then the fact that poor people can consume these items in 2014 and even rich people couldn’t consume them in 1954 is hardly a meaningful distinction,” said Gary Burtless, an economist at the Brookings Institution. “That’s not telling you who is rich and who is poor, not in the way that Adam Smith and most everyone else since him thinks about poverty.”

A version of this article appears in print on May 1, 2014, on page A1 of the New York edition with the headline: Changed Life of the Poor: Better Off, but Far Behind.

Leave A Comment