Beyond Ferguson there are countless race-related conversations. We are also talking about the police. When the two come together…Well, what do you think? A White Sheriff, His Black Son…What might the two say when they sit down to dinner? Race. Justice. Might a kitchen table conversation help us to better understand the links? Consider this family’s story. And again, please tell us what do you think.

White Sheriff Talks Race, Police With His Black Son

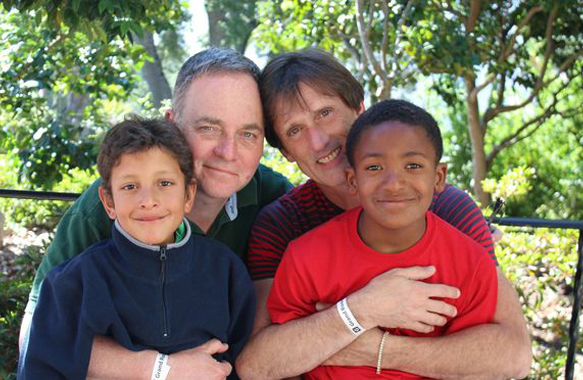

Photograph; Kevin Fisher-Paulson with his husband Brian and his sons Zane (right) and Aiden. (Stephanie Boone)

Join Takeaway Host John Hockenberry today at 6:00 PM Eastern/3:00 PM Pacific for a Twitter chat on Ferguson, race, justice, and America. Follow @TheTakeaway and use the hashtag #BeyondFerguson.

Last October, a police officer in Santa Rosa, California, shot and killed a 13-year-old boy named Andy Lopez. The Latino teenager was carrying a toy gun, which the officer said he believed was real. An hour away, at a home in San Francisco, Zane Fisher-Paulson was in shock.

“My son Zane sat at the kitchen table as we were listening on the radio about it and he started crying,” recalls Kevin Fisher-Paulson, Zane’s father. “And I said, ‘Zane, why are you crying?’ And he said, ‘Could that happen to me?'”

Fisher-Paulson is a deputy sheriff in San Francisco. He and his husband, Brian, are both white. Zane, 11, the older of their two adopted sons, is black.

For Fisher-Paulson’s multiethnic family — including 9-year-old Aiden, who’s mixed-race — Lopez’s death sparked a conversation about police and race that he’d never had to consider while growing up in a “pretty insular white, Irish-Catholic family.” Now the dinner table where he heard the news has become a frequent forum for race issues.

“Raising a black child has certainly awoken my awareness to race in America,” Fisher-Paulson says.

He’s had that awareness since he and Brian first adopted their children. The pair watched as strangers suspiciously eyed their children if they walked alone in stores, and even felt the strangeness among their well-meaning white family friends. Fisher-Paulson remembers one trip to visit family in Maine in a tone that’s still disbelieving: “One of his relatives said, ‘Oh my gosh, look how big his lips stick out.'”

'Children on a bus held their hands in the air and chanted "Hands up, don't shoot!"' http://t.co/Zk1BPyuMr7 #Ferguson pic.twitter.com/JFjZXfzo20

— NBC News (@NBCNews) August 20, 2014

Issues of race and policing have become particularly salient over the last ten days, since the police shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. Fisher-Paulson says he can’t shield Zane from the realities of being black in America. “I had to be honest with him in that, sometimes in the world, there are still people who will profile an 11-year-old boy simply based on his race,” Fisher-Paulson says.

He hopes that conversations like the ones that take place at his table can ease that tension. When Fisher-Paulson looks at the situation in Ferguson, he sees a clear lack of understanding between the police force and the community. “A community does not protest if they feel like they’re being heard. … There was no true and meaningful dialogue with the community about

And that dialogue is inseperable from race, he thinks: “That communication’s gotta come from a cultural competence, and the cultural competence comes from diversity.” It’s a particular issue in Ferguson, where the population is 67 percent black but the police force is almost 95 percent white — as are the mayor and six of seven city council members.

As for his own children, Fisher-Paulson admits that “I can’t say I live without fear.” Zane is getting older and stronger and more aware of the injustices around him. Fisher-Paulson has already experienced moments where Zane has lashed out in anger, yelling in public that his “real father” is black. “When Zane is most fearful, Zane feels that he is the most different … he will always go to his place of fear when he feels he’s different,” Fisher-Paulson says.

Of course, he returns to the kitchen table to fight that anger. “We may be different … but we are, ultimately, the same family. I have to live in that hope, and that my son can be a leader of that hope in the future.”

And in the end, he says the key questions that worry him are the same ones that keep any parent of any race up at night: “How can I keep my child protected when I’m not there to protect him?”

Leave A Comment