Now attention is turning to the schools' accreditors.

Schools need accreditors' stamps of approval to maintain access to the government's annual $170 billion in federal student aid.

Now attention is turning to the schools’ accreditors.

Accreditors are supposed to make sure that schools provide students with a quality education. They are not government agencies, but wield enormous power: Schools need accreditors’ stamps of approval to maintain access to the government’s annual $170 billion in federal student aid.

Losing accreditation would be fatal for most for-profit schools since they rely on federal aid for much of their income. But accreditors rarely crack down, even when students are struggling. One of the areas where students at for-profits face extra burden is debt: While only one-tenth of college students attend for-profit schools, they account for nearly half of all students’ defaults.

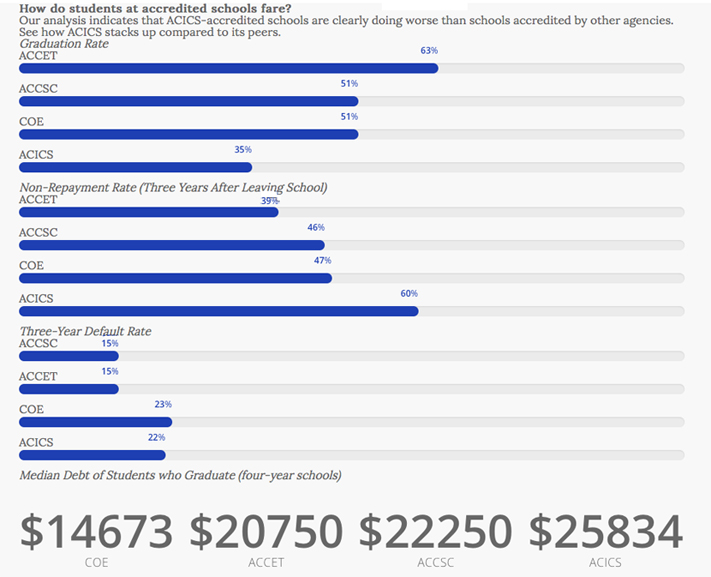

What role are accreditors playing? Using recently released federal data, ProPublica analyzed how students are faring under the various accreditors that oversee many for-profit schools.

One accreditor stands out: The Accrediting Council for Independent Colleges and Schools, also known as ACICS. It oversees hundreds of mainly for-profit schools where students struggle at remarkably high rates.

Just 35 percent of students at a typical ACICS-accredited four-year college graduate, the lowest rate for any accreditor. Nationally, the graduation rate at four-year schools is around 59 percent. (Read our methodology for details on how we crunched the numbers for our analysis.)

How do students at accredited schools fare?

Source: Department of Education Data; Note: We focused on the five largest national accreditation agencies and this chart only shows data for four-year programs. (See our methodology for more information.)

If you don’t graduate anyone, you can’t make claims that your program is any good, said Ben Miller, senior director for postsecondary education at the Center for American Progress.

Students at ACICS-accredited four-year schools also take on more debt than students at other schools with similar accreditors, typically about $26,000 in federal loans.

And then students struggle more to pay off the loans: At a typical ACICS-accredited school, about 60 percent of students were unable to repay even $1 of their loan principal within three years of graduation. That’s 23 percentage points higher than the national average. (Miller also did a study this summer that found that more than one in five students at ACICS-accredited schools default on their loans.)

Anthony Bieda, vice president for external affairs at ACICS, told ProPublica that the organization does hold schools accountable. While ACICS does not track student debt load and loan repayment, it does look at other indicators, such as job placement figures and default rates.

Bieda also says there’s a reason ACICS-accredited schools may look worse: they enroll poorer students. At a typical ACICS-accredited school, 75 percent of students receive federal grants designed for low-income families, a much higher proportion than similar accreditors.

The primary predictor of whether or not a student will default on their student loan is their economic circumstances, not the quality of the institution that they enroll in, he said.

Targeting poor students is exactly what regulators are concerned with. Take Corinthian Colleges, for example, which was the second-largest for-profit college chain in the country until it went bankrupt earlier this year. Before it closed down, the for-profit empire faced federal allegations of using deceptive advertising to lure poor students into predatory loans. Last week, a federal district court in Illinois found Corinthian liable for more than $530 million, the entire amount of the predatory loans.

Miller, who previously served as a senior policy advisor at the U.S. Department of Education, said that a student’s socioeconomic background is not the only factor that determines whether loans are repaid. No one would pretend that there aren’t demographic factors that influence results, but we can’t pretend the schools don’t have any effect too, he said.

The Obama administration appears to agree. A few weeks ago, the Department of Education announced that it’s about to launch a push for accrediting agencies to focus more closely on student outcomes.

Incoming Education Secretary John King, who will replace Arne Duncan at the end of the year, said in a press briefing on the changes that the focus in higher education needs to shift away from just enrollment towards completion, and particularly completion for the students who are most at risk.

The announcement comes in the wake of growing scrutiny of accreditation. A Wall Street Journal investigation earlier this year found the accreditors that focus primarily on nonprofit colleges also rarely hold schools accountable. And this past summer, Duncan called out accreditors for providing too little accountability, describing them as the watchdogs that don’t bark.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., has repeatedly called for the Department of Education to get tougher on for-profit schools. She decried the current state of college accreditation.

Accrediting agencies should not be allowed collect their fees, certify schools’ eligibility for billions in federal dollars, and then walk away when those schools defraud their students or leave students with huge bills for useless degrees, Warren told ProPublica in an email.

ACICS itself has faced increasing heat for accrediting campuses of Corinthian despite 20 state investigations into the for-profit college chain. In a hearing this summer, Warren slammed ACICS’ president, Albert C. Gray.

How many federal and state agencies need to file lawsuits against one of your colleges before your organization takes a second look at whether that school should be eligible for accreditation, and most importantly, federal money? she demanded.

Gray responded that the investigations were just allegations. All of these investigations that you’ve mentioned are just that: investigations, said Gray. Without outcomes from these investigations, we don’t have any evidence to take any kind of action.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau has also recently launched an investigation into ACICS, demanding information on schools that the organization has accredited. It’s not clear what the investigation is focused on.

A Department of Education committee is scheduled to review ACICS’ accrediting status next year.

ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for their newsletter.

Annie Waldman is a reporter covering education at ProPublica. She recently graduated with honors from the dual masters program at Columbia’s School of International and Public Affairs and the School of Journalism, where she was a recipient of the Pulitzer Traveling Fellowship. Her work has been published with the BBC, Vice, Mic, and The New York World.

This piece was reprinted by EmpathyEducates with the kind permission of ProPublica. We are grateful for the research, investigation, reporting and visual expressions.

Leave A Comment