By Rebecca Strauss | Originally Published at The New York Times June 16, 2013

Averages can be misleading. The familiar, one-dimensional story told about American education is that it was once the best system in the world but that now it’s headed down the drain, with piles of money thrown down after it.

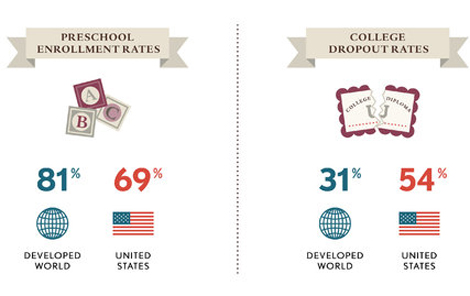

The truth is that there are two very different education stories in America. The children of the wealthiest 10 percent or so do receive some of the best education in the world, and the quality keeps getting better. For most everyone else, this is not the case. America’s average standing in global education rankings has tumbled not because everyone is falling, but because of the country’s deep, still-widening achievement gap between socioeconomic groups.

And while America does spend plenty on education, it funnels a disproportionate share into educating wealthier students, worsening that gap. The majority of other advanced countries do things differently, at least at the K-12 level, tilting resources in favor of poorer students.

Objective Subject/Threespot

Historically, the role of the federal government, which takes a back seat to the states in education, has been to try to close achievement gaps, but they have continued to widen. Several changes in federal education policy under President Obama have actually increased the flow of scarce federal dollars toward those students who need it less, reinforcing inequities and further weakening overall educational performance. Reversing America’s slide in international education rankings will require turning that record on its head.

America’s relative fall in educational attainment is striking in several dimensions. American baby boomers ages 55 to 64 rank first in their age group in high school completion and third in college completion after Israel and Canada. But jump ahead 30 years to millennials ages 25 to 34, and the United States slips to 10th in high school completion and 13th in college completion. America is one of only a handful of countries whose work force today has no more years of schooling than those who are retiring do.

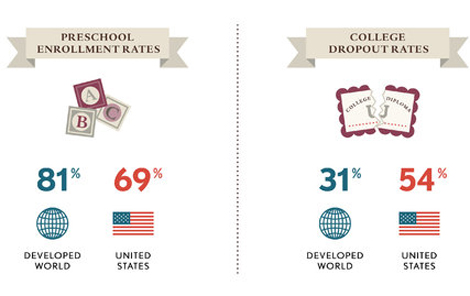

On international tests, American students consistently score in the middle of the pack among advanced countries, but America underperforms most on two measures — preschool enrollment and college on-time completion. Nearly all 4-year-olds in Japan, France, Britain and Germany are enrolled in preschool, compared with 69 percent in the United States. And although the United States is relatively good at getting high school graduates into college, it is horrible at getting them to graduate on time with a college degree. With more than half of those who start college failing to earn a degree, the United States has the highest college dropout rate in the developed world.

On average, money is not the problem. Given the country’s relative wealth, per-pupil spending on elementary and high school is roughly on track with other advanced countries. At the college level, the United States spends lavishly, far more than any other country.

The problem is that the United States is not spending its education dollars effectively. At every point along the education track, from preschool to college, resources are skewed to wealthier students.

The wealthy inhabit an educational realm very different from what national averages suggest. Consider these examples. If ranked internationally as nations, low-poverty Massachusetts and Minnesota would be among the top 6 performers worldwide in fourth-grade math and science. Among 15-year-olds, Asian-Americans, who also tend to be more affluent, are the world’s best readers; white Americans are third only to Finns and New Zealanders. In a 2012 Harvard Business School survey, high-quality universities were rated the country’s chief competitive advantage. The world’s brightest students clamor to attend them.

But educational excellence is increasingly the preserve of the rich. Everyone — black, white, rich, middle class and poor — is testing better and enrolling more in college than the previous generation. But rich students, and particularly rich girls, are making bigger gains than everyone else. Strikingly, these achievement gaps exist when children first begin elementary school and are locked in place all the way through to college.

Objective Subject/Threespot

Wealthy Americans have an advantage in the admission process for elite colleges, and despite the few who may slip in on family legacy, the advantage is largely based on academic merit. Students from families in the highest income quintile are now eight times more likely than students in the bottom quintile to enroll in a “highly selective” college, one that requires a high school transcript filled with As in advanced placement courses, SAT scores in the 700s and a range of enriching extracurricular activities.

Those who get in are doing better than ever. The best colleges are seeing their dropout rates fall to near-zero levels, especially for women. The education they offer is generally better than what students get at less selective schools, too. One very revealing fact is that even for equally qualified students, academic outcomes at selective colleges are better across the board and their graduates earn more and are more likely to progress toward an advanced degree.

The real quality crisis in American higher education — where the dropout rate is sky high and climbing — is in community colleges and lower-tier public universities. They have also absorbed most of the historic increase in college enrollment and disproportionately serve minority and low-income students. Money is a big reason for their worse performance.

At the college level, the divergence in per-pupil spending is staggering. Since the 1960s, annual per-pupil spending at the most selective public and private colleges has increased at twice the rate of the least selective colleges. By 2006, the funding chasm in spending per student between the most and the least selective colleges was six times larger than in the late 1960s.

In short, more money is being spent on wealthy students who have never been more prepared to excel in college. Meanwhile, poorer students who are less prepared — those who a generation ago would not have even enrolled in college — are getting a smaller slice of higher education spending. According to a study by the demographer John Bound and his colleagues, lack of institutional resources explains up to two-thirds of the increase in dropout rates at lower-tier colleges.

Of course, this divergence in educational investments begins long before college. Wealthy parents are piling on cognitive enrichment activities outside of school from preschool on up, and at a rate that is leaving everyone else in the dust. Schools could make up some of the difference by intensively investing in poor children, and the majority of richer countries do just that — spending more per pupil in lower-income districts than in higher-income districts. But it is the reverse in the United States, in large part because, unlike most other advanced countries, revenues for public schools continue to be raised mostly from local property taxes.

This record is a harsh indictment of the federal government’s efforts to promote greater educational equality. Out of the civil rights era of the 1960s and early 1970s sprang a host of federal programs whose sole objective was to close achievement gaps. One is Head Start, which now serves close to one million low-income 3- and 4-year-olds and has tried for many years, with modest success, to make sure they’re ready for kindergarten. For K-12 public schools, the federal government apportions money, called Title I and IDEA grants, to school districts based on the number of low-income or special-needs students they serve. Then there is the huge Pell grant program to help low-income students pay for college, which is the single largest component of the Department of Education’s budget.

Reversing the long-term trend toward education inequality would be an impressive feat for the Obama administration, which has tried to intelligently reform federal programs that serve low-income students. Nonetheless, some of the biggest changes in federal funding priorities have favored wealthy students.

Objective Subject/Threespot

On the plus side, the Obama administration has pushed for more cost and quality accountability for education providers who cater to low-income children, while also developing better ways to measure and evaluate quality. The worst Head Start preschools are being forced to re-compete for federal funding under a more rigorous set of standards. States are being encouraged, through No Child Left Behind waivers and the Race to the Top competitive grant program, to improve teacher evaluation techniques, to invest in data systems for tracking teacher performance and student achievement, and to refocus reform efforts squarely on the worst-performing K-12 schools.

At the postsecondary level, for the first time vocational college programs could soon be held directly accountable for a “gainful employment rule,” where they will lose federal accreditation if the programs’ costs outweigh labor market benefits for their graduates. In other words, programs would shut down if their graduates don’t land good jobs. There are also new initiatives promoting more transparency at all postsecondary institutions. The hope is that parents and students armed with better information will be better consumers and will punish schools with a record of charging too much or delivering too little.

Yet some of the administration’s most ambitious ideas for reducing education inequality have not been implemented. In spite of research that shows that high-quality preschool can make a positive — and ultimately cost-effective — impact on children’s cognitive development, President Obama’s call for universal preschool is going nowhere in Congress, mostly because it would be extremely expensive. The Obama administration has made no attempt to expand Head Start enrollment, even though half of all impoverished children are not enrolled in any preschool program.

At the college level, while Mr. Obama has placed community colleges higher on the federal agenda than any of his predecessors, his funding promises have gone unfulfilled. In his first term, he proposed three new community college funds totaling $25 billion and then a further $12 billion in stimulus. But in the end only $2 billion in direct aid for community colleges was appropriated.

What is most disappointing about the Obama administration’s oversight of educational programs, though, is the way the administration has arranged its funding priorities. Real baseline funding has been flat for Head Start, Title I and IDEA grants, and their financing will be cut by 5 percent under sequestration. It’s true that the number of Pell grant recipients has surged recently because more students are opting for college in the tough labor market, but Pell grant eligibility has been rolled back, with stricter limits put in place on income and lifetime eligibility. And even after a recent increase in the maximum Pell grant size, it still covers a much smaller share of a student’s college expenses than in the 1970s. The Pell grant program is also chronically underfinanced; it faces a $7 billion budget shortfall in 2014.

Where federal education policies have become much more generous, the benefits have disproportionately flowed to the wealthy. The administration has eased repayment terms for student debt, and the biggest gains will go to borrowers with the largest debt, who tend to be graduate or professional students with more earning potential. These already well-off graduates could end up receiving a federal subsidy that is four times larger than that provided to low-income students through Pell grants. Meanwhile, a new, more generous college tax credit also extended tax write-offs to families earning between $120,000 and $180,000. They reap most of the credit’s $10 billion in annual benefits.

Objective Subject/Threespot

These education-spending decisions are hard to justify. The politics are understandably tricky; middle- and upper-class families want relief from skyrocketing tuition bills, and poor families have a small fraction of their political clout. But a smarter allocation of scarce resources would focus on boosting lower achievers. Because sometimes averages don’t lie. Historically, broad educational gains have been the biggest driver of American economic success; hence the economist’s rule of thumb that an increase of one year in a country’s average schooling level corresponds to an increase of 3 to 4 percent in long-term economic growth.

In his first State of the Union address, in 2009, President Obama set a goal: America would regain the top spot internationally in the percentage of students graduating from college. No matter how much wealthier children keep gaining, there are not enough of them to raise that number. The only way America will again rise to the top in education is by lifting every student up.

Rebecca Strauss is associate director of publications for the Renewing America initiative at the Council on Foreign Relations. This article draws on research in a new council report, “Remedial Education: Federal Education Policy,” part of a series on restoring American economic competitiveness.

This post has been revised to reflect the following correction:

Correction: June 21, 2013

An earlier version of this column included a graphic that presented incorrect data. The gap in aggregate test scores between high- and low-income students born in 2000 was 75% greater than it was for those born in 1943; it was not a difference of 55 percentage points (127 to 72).

Leave A Comment