Photograph; Alice Terry Elementary School in Colorado. In the United States, more than half the money for school districts comes from local sources, mostly from property taxes.

By Eduardo Porter | Originally Published at The New York Times. November 5, 2013

“There aren’t many things that are more important to that idea of economic mobility — the idea that you can make it if you try — than a good education,” President Obama told students at the State University of New York in Buffalo in August.

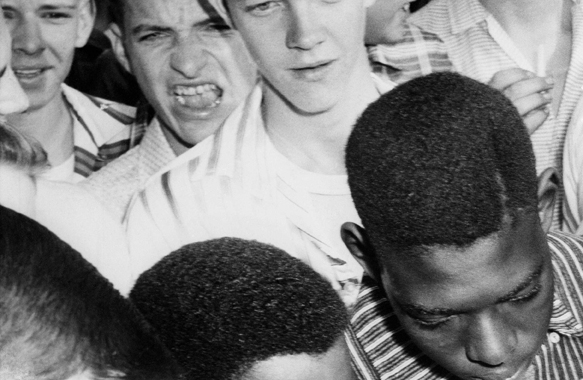

This consensus is comforting. It provides a solution everyone can believe in, whether the problem is income inequality, racial marginalization or the stagnation of the middle class. But it raises a perplexing question, too. If education is a poor child’s best shot at rising up the ladder of prosperity, why do public resources devoted to education lean so decisively in favor of the better off?

The anguished and often angry national debate over how to improve American educational standards, focused intently on grading students and teachers, mostly bypasses how the inequity of resources — starting at the youngest — inevitably affects the outcome.

“The debate about education reform is a lot about process,” said David Sciarra, executive director of the Education Law Center in Newark, an advocacy group for disadvantaged students. “To a large extent it is a huge distraction. We never get to the question of what resources we need to get the students to meet the standards.”

The United States is one of few advanced nations where schools serving better-off children usually have more educational resources than those serving poor students, according to research by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Among the 34 O.E.C.D. nations, only in the United States, Israel and Turkey do disadvantaged schools have lower teacher/student ratios than in those serving more privileged students.

Andreas Schleicher, who runs the O.E.C.D.’s international educational assessments, put it to me this way: “The bottom line is that the vast majority of O.E.C.D. countries either invest equally into every student or disproportionately more into disadvantaged students. The U.S. is one of the few countries doing the opposite.” The inequity of education finance in the United States is a feature of the system, not a bug, stemming from its great degree of decentralization and its reliance on local property taxes.

“Decentralization was wonderful for the initial diffusion of high schools,” said Lawrence Katz, a professor of economics at Harvard who helped write “The Race between Education and Technology,” one of the most comprehensive analyses of the spread of the American educational system throughout the 20th century. “But it created big geographic inequality.”

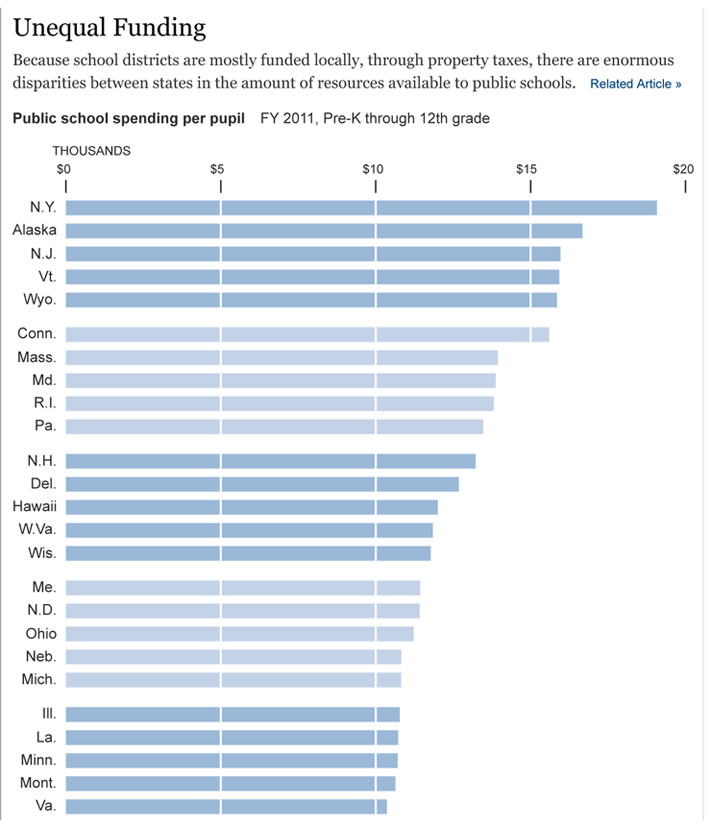

Today, the federal government provides only about 14 percent of the money for school districts from the elementary level through high school, compared to 54 percent, on average, among other industrial nations. More than half the money comes from local sources, mostly property taxes, which is about twice the share in the rest of the O.E.C.D.

This skews the playing field from early on. In New York, for instance, in 2011 the value of property in the poorest 10 percent of school districts amounted to some $287,000 per student, according to the state’s education department. In the richest districts it amounted, on average, to $1.9 million.

The state government in Albany redresses part of the imbalance: In the 2010-11 school year it transferred $6,600 per student to the state’s poorest school districts, about four times as much as it sent to the richest. But it’s still a long way from closing the gap.

That year, the most recent for which comprehensive data is available, the wealthiest 10 percent of school districts, in rich enclaves like Bridgehampton and Amagansett on Long Island, spent $25,505 on average per pupil. In the poorest 10 percent of New York’s school districts — in cities like Elmira, which has double the nation’s poverty rate and half its median family income — the average spending per student was only $12,861.

Disparities across the country are even starker. In New York, schools spend an average of $19,000 per student. In Tennessee they spend $8,200. The Alpine school district in Utah spends only $5,321. And funding in some states is even more skewed than in New York.

The Education Law Center compiles an annual report on the distribution of funding for education across the country, adjusting for variation in district sizes, teacher wages and school districts’ needs. Only 17 states, including Vermont, Massachusetts and New Jersey, provide more money per student to high-poverty districts than to low-poverty districts, it concluded. Funding is flat in 15 states.

In 16, including left-leaning states that provide lots of money for education like New York and in right-leaning states that provide very little like Texas, school funding is regressive. (Hawaii and the District of Columbia were excluded from their analysis.)

In Illinois and Nevada, New Hampshire and North Carolina, school districts with a poverty rate of 30 percent receive at least 20 percent less money per pupil than districts with a 10 percent poverty rate.

Can anything be done to close these gaps?

Parents, unions and advocacy groups have mostly relied on legal challenges, arguing that state governments have failed to provide adequate funding for education as required by most state constitutions. The Education Law Center counted dozens of lawsuits in 45 states since the 1960s, including one filed earlier this year by the New York State United Teachers and a handful of parents from poor districts like Elmira and Stillwater who also argued that property tax ceilings prevented poorer districts from closing the gap themselves.

Litigation has worked to some extent. But it is a blunt tool. In New Jersey , a host of state Supreme Court decisions over the last 30 years radically improved the funding in 31 poor urban school districts, and helped close the gap in test scores with more affluent schools. But one unintended consequence is that poor rural districts have lost funding.

Money, to be sure, is not a silver bullet that will automatically lift the test scores of poor American children and close performance gaps. How the money is deployed is absolutely crucial.

Still, the disparity matters a lot. Social and economic deprivation has a particularly strong impact on student performance in the United States. Differences in socio-economic status account for 17 percent of the variation in test scores, according to O.E.C.D. researchers, compared to 9 percent in Canada or Japan. In New York, according to Peter Applebee, an expert on education finance at the United Teacher’s union, only 18 percent of students in the poorest 10 percent of school districts scored above proficiency level in math last year. In the richest tenth, 45 percent did.

These gaps will be hard to close until the lopsided funding of education changes. As income and wealth continue to flow to the richest families in the richest neighborhoods, public education appears to be more of a force contributing to inequality of income and opportunity, rather than helping to relieve it.

Email: eporter@nytimes.com;

Twitter: @portereduardo

1. MA, NJ, VT have among the highest per pupil expenditures (education spending).

2. MA, NJ, VT have some of the top test scores and outcomes nationwide (pretty consistently, over time)

3. MA, NJ, VT are three of the 17 states that provide more money per student to high-poverty districts.

What can we learn from that?