By Catherine Cloutier | Originally Published at News 21. USC Annenberg. School of Communication and Journalism | Interact with the Shadow Secretaries of Education

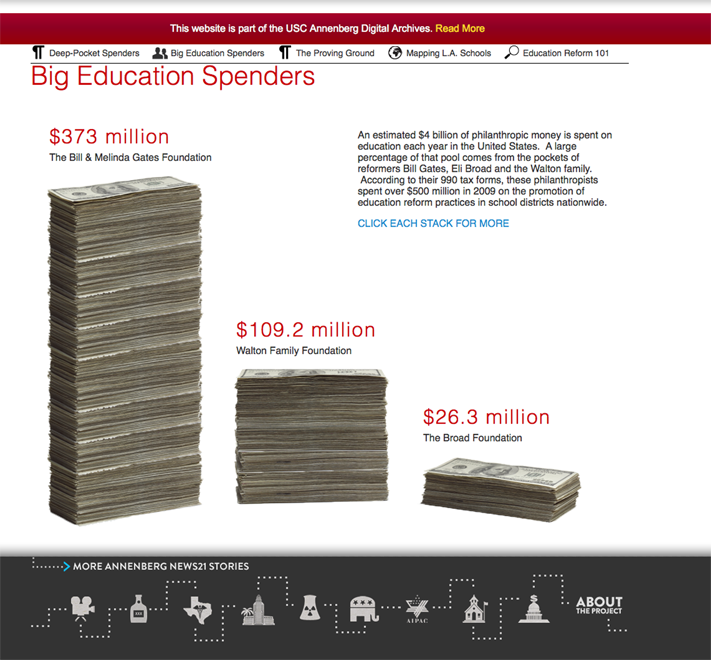

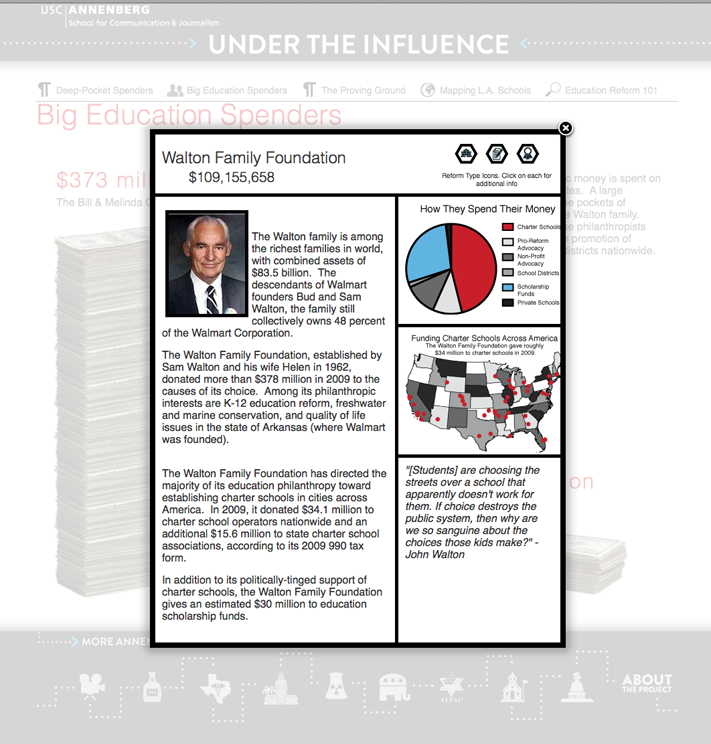

Gates is not the only billionaire who has decided to make education reform one of his pet projects. Los Angeles–based developer Eli Broad, the mega-rich Walton family (founders of Walmart) and other philanthropists currently give some $4 billion a year in contributions to education.

But these handouts are hardly purely philanthropic. They come tied with policy strings and a well-defined agenda.

While not the only donors, Gates, Broad and the Waltons have emerged as the highest-profile deep-pocket benefactors of what has become a nationwide education reform movement.

Though this push for reform of public schools dates back several decades, it has steadily moved from the margins of the political debate to occupy center stage in the tussles over domestic policy. The influence that these private philanthropists exercise is now being felt in school districts from coast to coast and manifests itself in the policies favored by the donors: the introduction of a corporate model in school administration, merit pay for teachers, giving local schools greater autonomy from their respective districts and the opening of more charter schools.

In these uncertain economic times where American families put an ever-higher premium on a good education, and with nagging doubts about flaws in funding in the public education system, the education reform movement has become a red-hot button. Reform advocates, like Gates and others in the private sector, fervently argue that the future of America depends directly on embracing the reform agenda.

“We’ve learned that school-level investments aren’t enough to drive systematic changes,” Allan C. Golston of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation told The New York Times in May

But opponents and critics of the reform movement, including most of the teachers’ unions and some leading education theorists, contend that the torrent of private money flowing into schools is not in the best interest of public education.

“I don’t think these ideas necessarily represent best practice, but they do represent political best practice,” says Rudy Crew, the former chancellor of New York City schools and a current professor at the University of Southern California. “They do represent what one person or one foundation believes and what they’ve put their money behind.

“America’s going to be very rudely awakened by all the money that has been spent with a shallow and empty drawer on the result side.”

In 1983, the National Commission on Excellence in Education released its assessment of the educational environment in the United States. It called the report “A Nation at Risk.” The report described “eroding” schools steeped in low performance and inefficiencies. Education policymakers were faced with the overwhelming question: How do we fix this?

Over the next two decades, steps were taken toward reform, including the opening of the first charter school in Minnesota in 1991. But the education reform movement did not take off until the enacting of the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, the education coup of the Bush administration. No Child Left Behind — which was supported by politicians on both sides of the aisle — required states to set achievement standards for basic skills. For critics, No Child Left Behind moved education reform from the right to the center of the political spectrum.

When President Obama entered office in January 2009, education reform became official education policy. The following July, Obama and his reform-minded Secretary of Education, Arne Duncan, announced the Race to the Top fund. Race to the Top encouraged states to compete for federal funding by submitting innovation proposals. Among the Department of Education’s criteria were statewide longitudinal data systems, evaluation of teacher and principal performance, strategies for improving low-performing schools and the removal of state caps on charter schools.

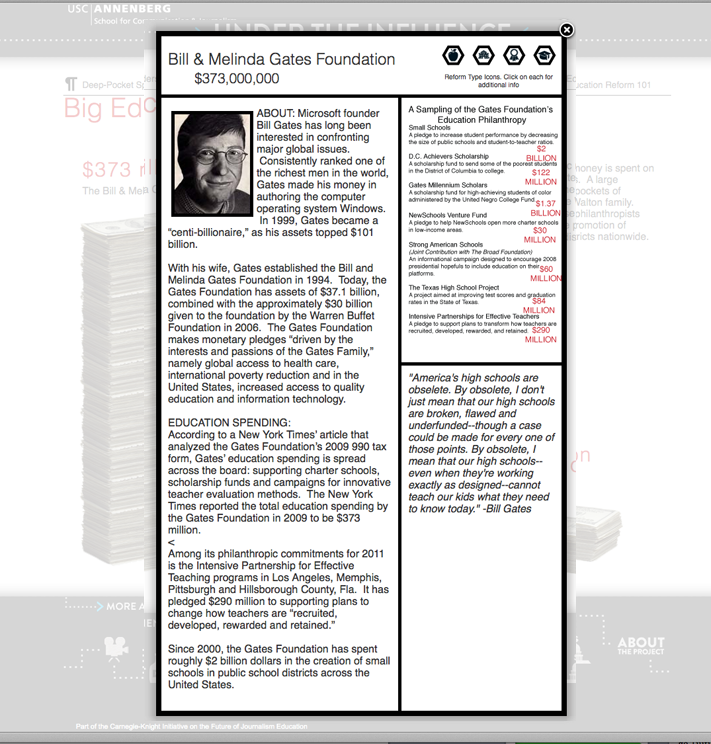

Race to the Top was funded by the $4.3 billion allotted for education in the president’s “stimulus package.” Yet, behind the scenes, funding came in from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The Gates Foundation reviewed the applications, picked 15 favorites and offered them up to $250,000 to hire consultants to draft the proposals

But Mike Rose, an education professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, and the author of Why School? Reclaiming Education for All of Us, says that the donations of Bill Gates and his reformer friends Eli Broad and the Waltons have taken education spending and influencing to a new level.

“When you’re trying to do things through your wealth and how you strategically place it, you’re starting to do things that have a direct effect on education policy. That’s new,” says Rose.

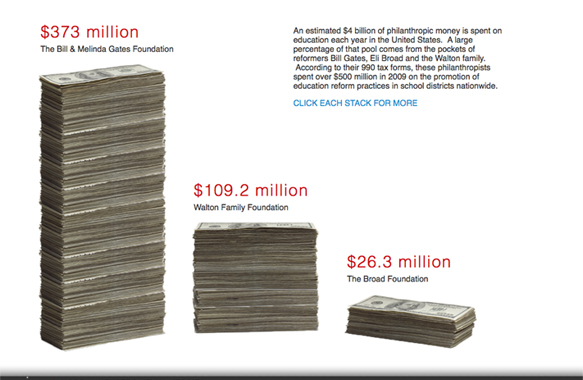

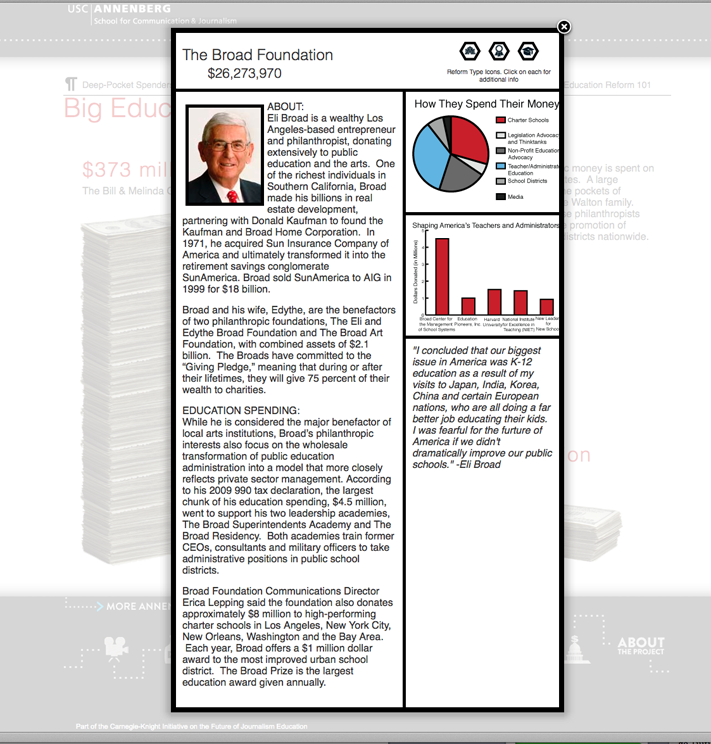

The New York Times reported in May that according to its 2009 990 tax report, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation spent $373 million on education. The Broad and Walton foundations donated $26 million and $109 million respectively in 2009.

After an unsuccessful venture into building “small schools,” the Gates Foundation has turned its attention to teacher evaluation methods and merit pay systems. Its recent $60 million pledge to the College-Ready Promise coalition seeks to provide innovative teacher evaluation practices in high-performing charter management organizations in Los Angeles.

The Walton Family Foundation, conservative in persuasion, donates extensively to charter schools — at about $250,000 a pop.

The Broad Foundation runs two education administration academies. The Broad Superintendents Academy trains former education administrators in management skills. A quarter of the Leadership Academy’s students come from industries other than education. The Broad Residency program installs graduates in administrative roles at school districts and charter management organizations.

The reach of these private foundations has extended into the public realm. Joanne Barkan reported in “Got Dough? How Billionaires Rule Our Schools” in Dissent Magazine that at least six higher-ups in the Department of Education came from the Gates and Broad camps. Duncan himself served on Broad’s education division’s board of directors.

The relationship between these philanthropists and the Obama administration is uncanny. Obama legislates reform; Gates, Broad and Walton pay for it.[emphasis addeda]

Citing scholarship by his former student, University of California, Berkeley, professor Janelle Scott (“The Politics of Venture Philanthropy in Charter School Policy and Advocacy”), Rose argues that the sway of foundation money on education policy is completely undemocratic.

“Public schools are being affected in a strong way by people who are not elected to office with money that is not vetted or channeled through public mechanisms,” Rose says.

“That’s why more than a few pundits refer to Bill Gates as the shadow Secretary of Education,” he adds.

The reach of Gates, Broad and Walton money can be seen in the policy shifts in the Los Angeles Unified School District — the home of the largest number of charter schools in the country, the practice field of innovative teacher evaluation methods, the epicenter of education reform.

Leave A Comment