Project Description

When I was in middle school, I was bused to the other side of town for my education. Portland Public Schools wanted to integrate middle schools in Southeast Portland. This meant that a handful of black students—most of us from Northeast Portland who had attended elementary school together—boarded a yellow school bus before sunrise to ride across town. We sat at the back of the bus laughing at the boys stinging on each other with yo momma jokes.

My best friend and I shared the headphones to her Walkman so that we both could sing along to Bell Biv DeVoe and Mariah Carey. For the 30-minute ride we were ourselves and there was no shame in the way we talked or related to each other. No one made a big deal about seeing my hair in braids one day and straightened the next.

We bragged about how well our mommas cooked and shared our leftovers with each other at lunchtime, even though one day a white girl loudly whispered to her friend that 'black food smells bad.'

But when I got to school, I felt invisible. Which is ironic because I was a plump dark-skinned girl with hair that would kink and curl at one drop of rain.

I stood out.

So how is it that I felt no one saw me?

Being seen—truly seen—is to feel that all parts of who I am are recognized not as compartmentalized pieces of myself, but blended truths of my identity. So when my white friends told me they didn’t see me as a black girl that meant they didn’t see me. When white teachers seemed shocked to hear me speak black vernacular in the hallway with my friends when I “spoke so well in class,” what they didn’t understand is that code-switching came natural to me—I talked both ways and I wasn’t trying to fit in with my friends or impress my teachers. I was being myself.

One day, on our way to a field trip to see the Oregon Symphony, a teacher tried to assure me that if I “gave the music a try” I might really find that I liked it. I told her that I loved classical music. That I loved jazz, too. Her smile told me that she thought this was a good thing. When she said, “Well, that’s good because that rap stuff is not music,” I told her that I loved hip-hop and R&B and gospel and country, too. My family was a musical family. We had a collection of records that included Tennessee Ernie Ford, Mahalia Jackson, Marvin Gaye, and the Jackson 5. My sister played in a jazz ensemble that traveled to Europe. My grandfather played the piano at church.

She didn’t seem to value the variety of music I enjoyed. There was clearly one that was better than the others and I took this to mean that the black parts of me were better off hidden. There was a shame that came with owning up to the parts of me that fit the stereotypes and assumptions of what people expected black children to be like.

In middle school I learned that some adults saw me as an “exception to the rule.” To be called confident for an overweight, dark-skinned black girl was to say that overweight, dark-skinned black girls had low self-esteem. If I was smart for a black girl that meant the rule was black children weren’t normally smart.

It was one thing to feel different, to be different. It was another thing to be judged on those differences. To realize that people had expectations of me because of what I looked like or the neighborhood I was from.

I often excused racist or insensitive remarks and actions, and instead blamed myself or thought that maybe I was taking it the wrong way.

But there was no excusing away what my 7th-grade science teacher said the day she passed out the tests we had taken a few days before. She walked to the front of the room and yelled, “I am so disappointed in all of you!” She paced the floor, walking between our desks. “None of you passed the test. You will be taking it again. Right. Now.”

I looked down at my paper. Saw the capital A scribbled in red ink across the top of the page.

“I will give you a chance to look through your notes and then you will retake the test.”

I looked back at my paper. “But I have an A,” I said. First to myself and then out loud when I raised my hand and asked, “Do I have to retake the test?”

“Oh, that’s right,” my teacher said. “You got an A.” She turned her back to me and addressed the rest of the class. “And this is why I am so disappointed in all of you. You let Renée Watson come all the way over here from Northeast Portland and get a better grade than you in science!”

I have often replayed that day in my mind. I have thought of new endings where I stand up for myself and walk out of class refusing to be humiliated. I have wondered what would have happened if she asked me to be a tutor for the other students in class. What if she taught me—and the rest of the class—about black scientists and their revolutionary discoveries? What if she had allowed space in her narrative for black children from Northeast Portland to be capable of meeting high expectations, of achieving academic success?

What if she really saw me?

As an educator, I try to see my students. I encourage them to embrace all parts of their culture—where they come from, what they eat, the music they enjoy, the joyous and disastrous parts of their neighborhoods and families. I strive to learn their individual and collective histories. I share my stories with them, and we grow and heal together. We laugh at ourselves for sometimes being the stereotype. We proudly proclaim that we are more than the stereotype. We mourn and rejoice over our ancestors—their struggles and victories, their shortcomings and strengths. We commit to sharing our true selves. We commit to seeing each other.

black like me

and suddenly everyone would see

how black i am.

black like collard greens & salted meat simmering on a stove.

black like hot water cornbread & iron skillets, like juke joints & fish frys

black like soul train lines & the electric slide at weddings and birthdays

black like vaseline on ashy knees, like beads decorating braids

black like cotton fields & soul-cried spirituals.

my skin is black

like red kool-aid, red soda, the red blood

of the lynched and assassinated and the african man

those skinheads killed with a baseball bat when i was in the fifth grade.

i am as black as he was.

my science teacher knows this. she sees

my black and is blind to my brilliance.

can’t believe i passed the test with an a

when all the white kids failed.

and when she says to the white students,

“you ought to be ashamed of yourselves . . .”

what she really wants to say is, “i can’t believe this black girl is as smart as you.”

all the white kids look at me

and this is when we learn that the color of our shells

come with expectations.

i stop being good

at science and math.

my english teacher gives me books and journals

and i read and write the world

as it is, as i want it to be.

i read past my black blues, discover that i am black

like benjamin banneker and george washington carver

black like margaret walker and fannie lou hamer

i am not just slave and despair.

i am struggle and triumph. i learn

to live my life in the searching, in the quest:

can i be black and brilliant?

can i be jazz and gospel, hip hop and classical?

can i be christian and accepting?

can i be big and beautiful?

can i be black like me?

can anyone see me?

—Renée Watson

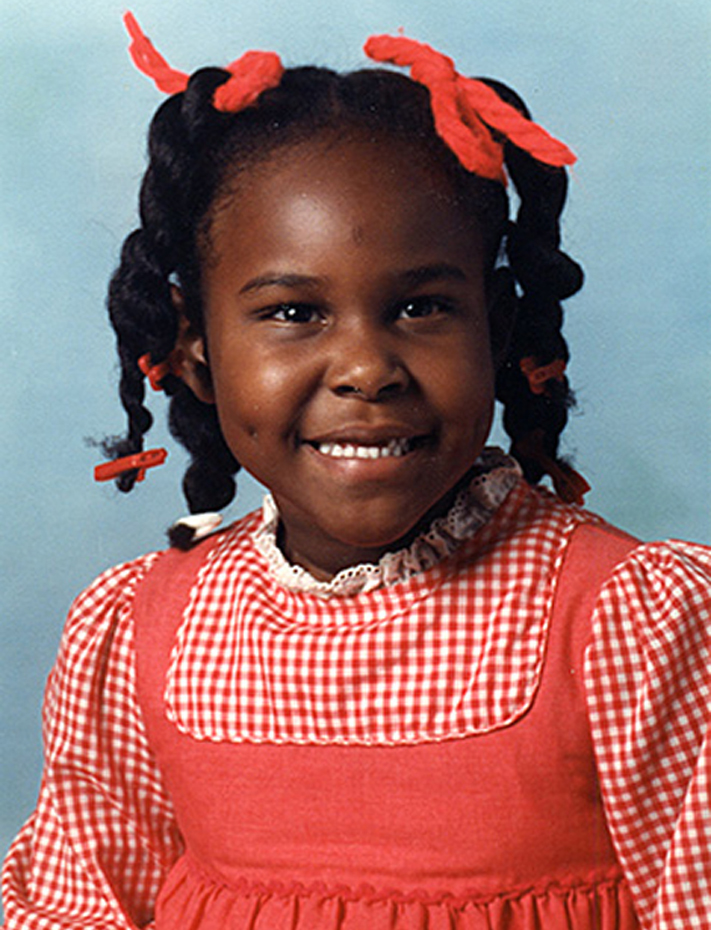

One of Renée’s passions is using the arts to help youth cope with trauma and discuss social issues. Her picture book, A Place Where Hurricanes Happen (Random House, 2010), is based on poetry workshops she facilitated with children in New Orleans in the wake of Hurricane Katrina and was featured on NBC Nightly News with Brian Williams.

This piece was republished by EmpathyEducates with the kind permission of the Author. We thank Renée Watson for her insights, her poetry and for a novel and beautiful wisdom and ReThinking Schools. for ever improving the education conversation.