Originally Published at Deb Meier. December 31, 2013

Dear readers,

It’s been a while since I’ve written in this space. But I’m mending my ways.

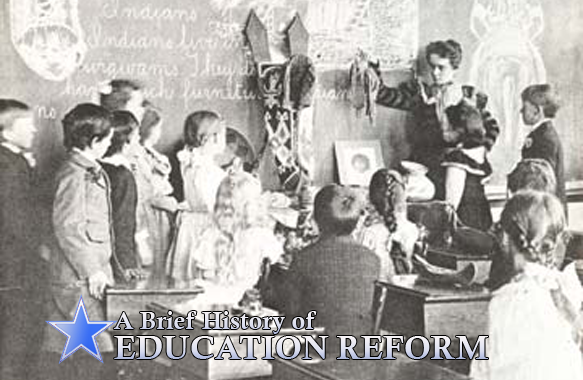

What set me off? My granddaughter just came across something interesting—and not new. In 2001 PBS put together a video called School: The History of American Public Education. In connection with the film they listed ten significant individuals who had an impact on American public education. And I was one of the ten! It’s an interesting list. It starts with some obvious names: Horace Mann and John Dewey and Booker T. Washington. And then adds a number of individuals who I didn’t recognize at first. John Joseph Hughes who, as Archbishop of NYC, initiated the widespread development of parochial Catholic schools in the late 19th century; Catherine Beecher who pioneered schooling for women; Ellwood Cubberley who a century ago promoted scientific management of schools; Albert Shanker whose life personified the growth and influence of teacher unionization; Linda Brown Thompson—the Brown of “Brown vs Board of Education”; Jose Angel Gutierrez who as a Texas community organizer led the movement for bilingual education. The final two are E.D. Hirsch, Jr who pioneered the idea of a “common core” curriculum (which is now embodied in DOE policy in 48 states), and me–Deborah Meier! The description of my work suggests that I made an impact by demonstrating how small democratic public schools could successfully educate low-income Black and Latino kids.

What’s interesting is precisely how varied the list of “reformers” is—representing contradictory developments that still have an impact on American public schools. It helps see how the back and forth of our history was responding to changes in society itself and how many different viewpoints have influenced schooling, reflecting its specific time and circumstances. Interesting, the two most recent individual innovators (Hirsh and I) both champion very different approaches, but both do so in the name of furthering democratic ideals. Hirsh focuses on a “common” curriculum as the route to a better society, and has offered his detailed K-12 approach, which, with some variations, has recently been embedded in national policy.

I have focused on the school itself as a community, one that teaches democracy as an institution. Both pedagogy and curriculum are shaped democratically, teaching in the process what it means to be a member, a citizen. Thus, as Dewey posed it, it’s a form of associated living, which builds on the mutually respectful relationships between family, school staff, students and community. While agreeing on a few broad principles that unite us as a people, I’ve argued on behalf of schools delegating the endless array of decisions that must be made amongst its members. Some would adopt Hirsch’s curriculum, some would have detailed grade-by-grade mandates, some would make more use of technology than others, some would leave most pedagogical and curricular decisions to its faculty, etc. But accountability would rest, as it does in a democracy, on the work of its leadership, which would—except for issues dealing with civil rights and health and safety—be responsive to those it serves.

What was only two decades ago the primary “reform” movement is now hanging on tenaciously, but has far less support in places of power. The new reformers have borrowed from Cubberly, remind us of the struggle over mass public education in the first half of the 20th century. This was a period in which corporate practices—the assembly line ideal—had a serious influence, and labor unions were largely taboo in public service, including teaching. Pay-by-performance goes back to this period, along with many other new ideas coming from the new reformers led largely by powerful and often wealthy non-educators, think-tanks and corporate Foundations.

In this context I welcome the new mayor of NYC’s appointment of an educator—Carmen Farina as our new Chancellor. She’s a first in a long time—following four people who made their reputation in business, Wall Street, or political life. DeBlasio’s campaign promises—which included pre-school education and considerable skepticism about the role of testing and charter schools—is encouraging. Who knows who, a century from now, will be considered representative of the late 20th and early 2lst century.

That story is yet to be written. But, of course, I’m cheering “my side”—which does not mean schools just like “ours”, but schools in which the “public” in the form of real-live school-based adults have a serious and respected role in most important decisions, and when what’s good-enough for the children of the rich won’t be viewed as “beyond the reach” (fiscally or intellectually) of all citizens.

Deb

Leave A Comment