Walter Dyett High School, pictured here, is being phased out by the Chicago Public Schools. Since 2001, the district has closed, phased-out or turned around about 150 schools. The vast majority of the students affected by the school closures have been poor or African American.

Introductory Essay By Betsy L. Angert | Published at EmpathyEducates. December 26, 2013

We mistakenly believe children are resilient. They will not remember or at least not be affected. We see those sweet smiles, those eyes full of dreams – and what do we perceive? To be young and full of hope, to see the scope of possibilities…to conceive, and to trust that if we believe we will achieve, or will we? “Mom, look at me.” Daddy, what to you see in my future? Will you help me? Teach me to read. Take me to school.” I too want to acquire the necessary tools and feel a part of something bigger.

When we were young we understood that school was our other home. It had a heart, and it gave us our start. It was in school that we grew; plants and the animals did too…with our teacher’s help. At the neighborhood school we had friends. Our family too attended. For generations, we were one. We came of age, at and through school.

School was a sanctuary of sorts. It is where we found safety. There was security too in the form of stability. You had your desk, and I had mine. We each had our own books, pens, pencils, and way back then there was paper, all supplied by our school. Everyone belonged. In school we each found ourselves and a path to the future! What do I want to be? I did not always know, but I was sure that at school I could be me.

No, it was not always fun. There were follies and failures. Nonetheless, even in playthere was learning. Fall as I might, there was always someone to lend me a hand. A person, a poster, a place in the room. From my seat I could see what spoke to me, the words of a master. I can accept failure, everyone fails at something. But I can’t accept

This notion is universal. We each try to achieve. We live and we breathe. However, for some there are barriers. We are born into circumstances beyond our control, and even a parent, try, as they might, cannot save us. Moms and Dads want us to thrive, but first comes the need to survive.

A Mom or Dad’s job, a parent’s schooling can necessitate a move. Family dynamics too can present the need to leave or to follow. Bad as these may feel or be, when we are forced to change locations it is worse.

Moves interrupt friendships. To a new child at school, it may at first seem that everyone else has a best friend or is securely involved with a group of peers. The child must get used to a different schedule and curriculum, and may be ahead in certain subjects and behind in others. This situation may make the child stressed, anxious or bored.

Again she is me. He is you, and we…We are one. Be we Black, white, or Brown, olive in hue, golden or pink, purple too, we want to be close. Our communities are our kin. Connectedness has no skin. Our cities cannot define our station. However, studies tell us often these do. There are The Stealth Inequities of School Funding.

We can Measure Inequity in School Funding. Public School Funding Unequal: State and Local School Finance Systems Perpetuate Per-Student Spending Disparities. That is the Black and white of it in cities schools. Court decisions too have secured what is. As a society we have settled; separate and unequal these are our schools.

As children we are not blind. We know. We know where we want to go school and why. The Bronzeville students share their stories of Dyett High School. Parents in the community also offer their history and lament what will soon disappear; doors to their home away from home will close. And we will rob them of their dreams and memories.

References and Resources…

- Play and children’s Learning. National Association for the Education of Young Children

- Faces For Families. Children and Family Moves. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. March 2011

- Measureing Inequity in School Funding Center For American Progress. August 2011

- The Black and White of Education in Chicago’s Public Schools Chicago Teachers Union.

- The Stealth Inequities of School Funding. Center For American Progress. September 2012

Amid Mass School Closings, A Slow Death For Some Chicago Schools

CHICAGO— After Parrish Brown graduates from Walter Dyett High School this spring, it’s likely he’ll never set foot in that school building again. Not for a 10-year reunion or to catch up with former teachers or to admire the gleaming trophies inside the school’s display case.

Because if all goes according to the city’s plan, there soon will be no Walter Dyett High School to return to in Bronzeville, an historic African-American enclave on the city’s south side.

“They closed my elementary school and now they’re phasing out my high school. One day there’ll be nothing in my community to come back to,” said Brown, 17.

“Phasing-out” is a euphemism for slow death in a district that has become increasingly aggressive about closing public schools in poor and African-American neighborhoods.

Dyett is scheduled to close at the end of next school year, at which point, community groups say, there will be no other viable public high school in the neighborhood–essentially creating a “school desert.”

PHOTO BY TRYMAINE LEE FOR MSNBC

Parrish Brown, 17, is a senior at Walter Dyett High School in Chicago’s historic Bronzeville neighborhood. Dyett is on the list of schools being phased-out by Chicago Public Schools. When the school closes there will be no other viable public high school in the neighborhood, creating what critics of the closure call a “school desert.”

In Chicago and nationwide the school closings have destabilized tens of thousands of mostly African-American students. About 88% of the students affected by the Chicago closings are African-American, 10% are Latino and 94% come from low-income families.

Opponents of the closings say officials with Chicago Public Schools (CPS) and the school board have essentially sabotaged neighborhood schools by starving them of resources, claiming the mayor’s appointed school board has served as enforcers for the mayor’s pro-business agenda to privatize public education. As the district has been active in closing and defunding public schools, a flurry of new charter schools has sprung up across the city. Just last week, CPS proposed the addition of 21 new charter schools.

“They are choking these schools out and they know exactly what they are doing,” said Steven Guy, a member of the Local School Council at Dyett. “This slow death does more damage. It’s psychologically damaging to the children. We’ve already lost one generation, and we’re about to lose another.”

The closings were meant as a cost-cutting measure to buoy the beleaguered district, which is facing a budget deficit of nearly $1 billion. This school year CPS cut about $180 million from direct classroom spending and central office expenses, in addition to laying off nearly 2,000 teachers. Decades of population decline had left many of the city’s schools far below capacity, and the district sought to consolidate resources and students.

But some of the schools, as is the case with Dyett, are being phased out because of “chronic academic failure and the need for higher quality educational options for students,” according to CPS’s plan for the school. In the most recent round of state testing, only 6.5% of the school’s 11th graders met or exceeded state standards in reading, math and science, despite recent improvements in graduation and college acceptance rates.

Prior to this year’s school closings, CPS had closed, turned around or converted to charters or selective enrollment 20 area schools since 2001, according to a 2012 report by the University of Illinois at Chicago. Between 2005 and 2010, four high schools not far from Dyett were closed.

PHOTO BY TRYMAINE LEE FOR MSNBC

Parkman Elementary located on Chicago’s South Side is one of 47 schools closed by Chicago Public Schools over the summer.

At the same time CPS began to financially disinvest in the school, leading to crucial programs being cut, including popular college preparatory programs.

“This is not about school choice. If it was really about providing us with choices, we’d have the choice to improve our neighborhood schools,” said Jitu Brown, the education organizer at the Kenwood Oakland Community Organization (no relation to Parrish Brown the high school senior). “When you shut down neighborhood schools you’re not providing choices, it’s displacement by force.”

‘School is their only stability’

At the start of last school year, more than 30,000 Chicago public school teachers went on strike, walking out as negotiations with the school board broke down and talks with Mayor Rahm Emanuel became increasingly terse. The strike was widely regarded as a win for teachers, albeit with concessions.

But in the year since the strike, the euphoria over the modest gains has faded, muted by what teachers and analysts describe as battles on all fronts. There were the school closings and the layoffs. And crippling budget cuts–so deep that teachers tell of having to buy toner for their classroom printers or purchasing toilet paper, as well as additional layoffs in schools already strapped for vital academic resources.

Dyett laid-off 16 teachers this year. The school is an extreme but not atypical example of the impact felt on individual schools and the students they serve, as the layoffs and budget cuts ripple far beyond the classroom.

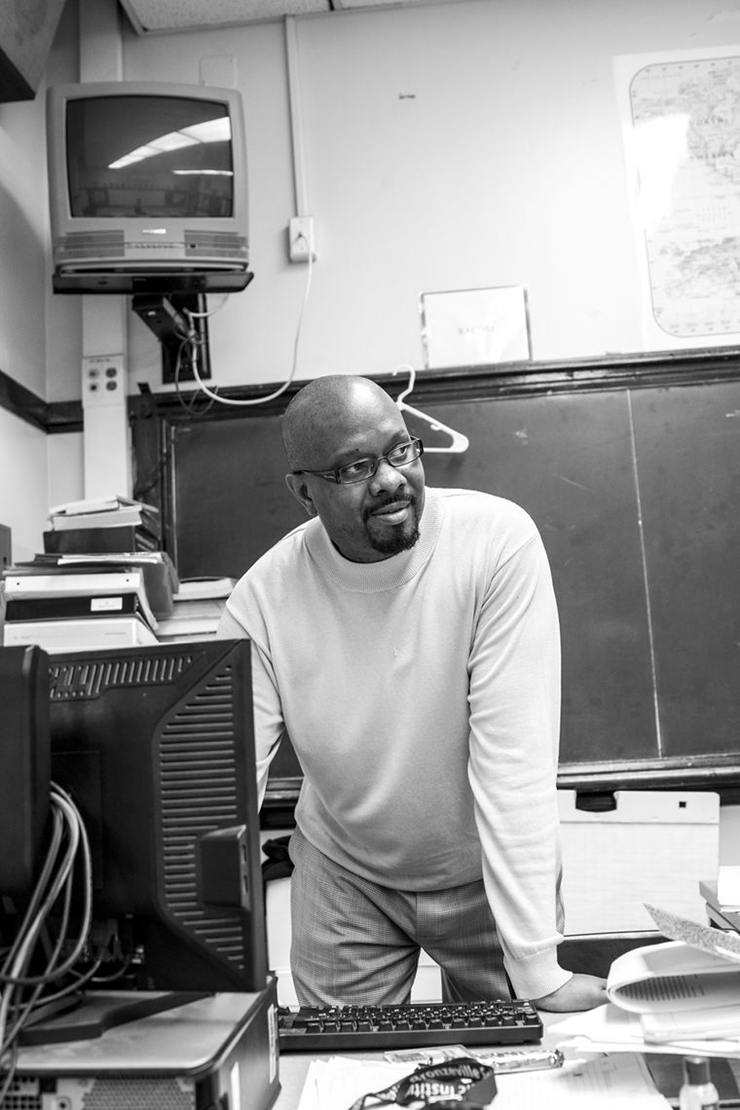

PHOTO BY TRYMAINE LEE FOR MSNBC

Reginald Grigsby, a history teacher at Bronzeville Scholastic Institute, said the impact of Chicago’s school closings and deep budget cuts have not just impacted school buildings, but disrupted the teacher-student relationships, some of the most stabile relationships that many students know.

Grigsby was among the teachers laid off earlier in the year, and was one of only a handful of African-American male teachers at his former school. He said more than simply dislodging students and teachers from buildings, the cuts and closings dislodge students and teachers from each other’s lives.

“I think the people sitting in an office Downtown making decisions that affect many of these kids don’t realize that school is their only stability,” Grigsby said. “Once the educator is removed from the equation, nobody’s looking at how the children will be affected, when the one thing that has been stable is removed.”

‘Our school is not preparing us.’

The nearest high school, Wendell Phillips Academy, is more than two miles away and is a so-called turnaround school. Because of its history of poor academic performance, the city has appointed a private management company to run the school. Other options on the south side include a school that’s already overcrowded, charter schools or one of the city’s selective enrollment schools.

As a school on the district’s phase-out list, Dyett has found itself in a kind of social and academic limbo. The school is in the second of a planned three-year phase out. It stopped accepting incoming freshman and its budget has been slashed dramatically. Much of its staff has been laid-off. Honors classes have been scrapped. Because of the teacher layoffs, core classroom instruction such as algebra and biology has been replaced with online classes. So have courses like gym and art, as well as the school’s limited number of advanced placement classes.

“CPS promised us that by the time we left we’d have all the resources we’d need to graduate,” said Parrish Brown. “Senior year you’re supposed to be worried about college applications, actually getting into college and not about stuff that we shouldn’t be thinking about.”

Brown worried about the impact the school’s limited curriculum might have on his college prospects, complaining that his online AP classes, including a politics and government class, haven’t “given me the real classroom experience.”

“Our school is not preparing us for anything after we graduate,” he said.

“The students knew this was going to happen. We all did. And even though you know what’s going to happen and you know what the plan is, I think there is still that glimmer of hope that they might change their minds,” said June Webb, a science teacher at Dyett. “But it doesn’t look like that will happen.”

Charles Campbell, the school’s principal, said “the challenge is keeping everybody focused on graduation rather than the school closing.”

“The school is going to close, we know that, but you still need to graduate and we want to graduate you at the top of your game,” Campbell said. “We have to take the excuses away.”

Andrea Zopp, president of the Chicago chapter of the National Urban League who also serves on the Chicago school board, said the academic and cultural conditions at many of the schools the board has closed were deplorable, and that closing them was the best course of action.

“We had some horrible schools,” Zopp said.

Zopp said that schools in many of the city’s poorer, minority communities simply weren’t adequate options for parents. She lamented that even if a child made it to school on time each day, studied hard and graduated from the 8th grade, “they would not be at the place they should be.”

“The school system failed them,” she said. “That bothers me more than any other issue and as I’ve said multiple times during the time we were closing schools, before we were closings schools, not one of these community groups ever came to me and said that it’s an abomination that the school district is running schools in our community that are not preparing our children.”

In recent weeks Zopp said she has visited about 10 schools that have received students from closed schools, and by her estimation those students are much better off than they were a year ago.

“There’s more actual learning going on in the classrooms,” she said.

Last year, a group of Dyett students filed a federal civil-rights complaint against the city, trying to keep the school open by saying the closure is a denial of their rights to an adequate public education.

“It just feels like they don’t care as much as we want them to,” said Walter Flowers, 17, another senior at Dyett. “It’s been heartbreaking. CPS just turned its back on us. Our minds could be used for so many opportunities, but I think they’re trying to shut all of that down to keep us down.”

Earlier in the week, Flowers, Brown and fellow Dyett senior Diamond McCullough, 17, joined hundreds of other protesters marching from City Hall to the nearby State of Illinois building where the governor’s Chicago office is located. The event was part of a national “Day of Action” that included similar rallies in dozens of cities across the country, in which teachers unions, parents and students demanded an end to school closings and the privatization of public schools. In Chicago, people delivered signed holiday cards or lumps of coal to local politicians, depending on how they’d supported neighborhood schools.

“I just think like, all the schools closing in black and brown areas, it’s like, who do we turn to,” McCullough said mournfully. “You’re supposed to be able to work with the school district instead of having to work against them.”

PHOTO BY TRYMAINE LEE FOR MSNBC

Diamond McCullough, 17, a senior at Dyett, and friends cheer on the Dyett Eagles during a recent home game. McCullough and other students at Dyett have protested the school’s closure and have filed a federal civil rights complaint in an effort to keep the school open.

Leave A Comment