By Marian Wang | Originally Published at ProPublica. October 15, 2014, 5:45 AM

Every Year Millions In Public $$ Go To This Entrepreneur’s Charter Schools and For-Profit Companies He Controls.

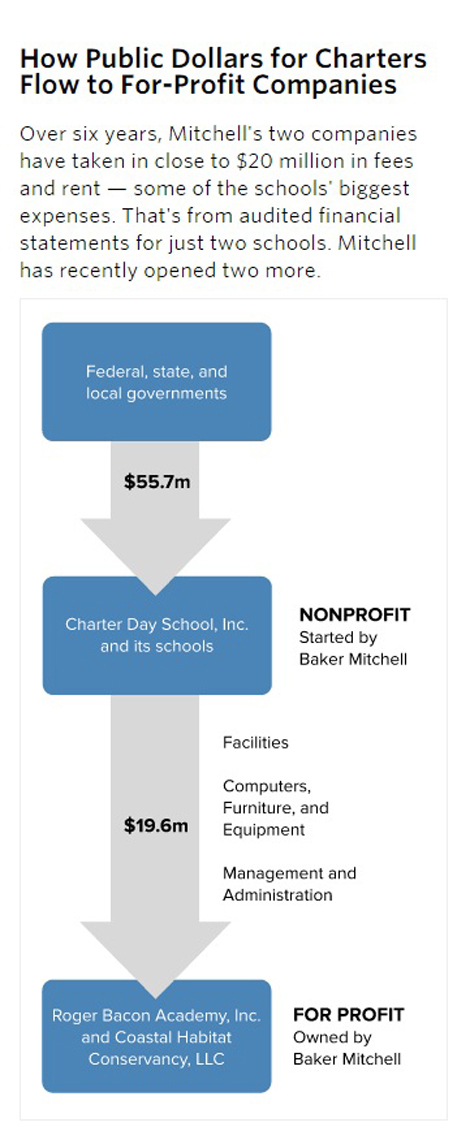

Baker Mitchell is a politically connected North Carolina businessman who celebrates the power of the free market. Every year, millions of public education dollars flow through Mitchell’s chain of four nonprofit charter schools to for-profit companies he controls.

Versions of this story were co-published with The Daily Beast and the Raleigh News & Observer.

In late February, the North Carolina chapter of the Americans for Prosperity Foundation — a group co-founded by the libertarian billionaire Koch brothers — embarked on what it billed as a statewide tour of charter schools, a cornerstone of the group’s education agenda. The first — and it turns out, only — stop was Douglass Academy, a new charter school in downtown Wilmington.

Douglass Academy was an unusual choice. A few weeks before, the school had been warned by the state about low enrollment. It had just 35 students, roughly half the state’s minimum. And a month earlier, a local newspaper had reported that federal regulators were investigating the school’s operations.

But the school has other attributes that may have appealed to the Koch group. The school’s founder, a politically active North Carolina businessman named Baker Mitchell, shares the Kochs’ free-market ideals. His model for success embraces decreased government regulation, increased privatization and, if all goes well, healthy corporate profits.

In that regard, Mitchell, 74, appears to be thriving. Every year, millions of public education dollars flow through Mitchell’s chain of four nonprofit charter schools to for-profit companies he controls.

The schools have all hired the same for-profit management company to run their day-to-day operations. The company, Roger Bacon Academy, is owned by Mitchell. It functions as the schools’ administrative arm, taking the lead in hiring and firing school staff. It handles most of the bookkeeping. The treasurer of the nonprofit that controls the four schools is also the chief financial officer of Mitchell’s management company. The two organizations even share a bank account.

Mitchell’s management company was chosen by the schools’ nonprofit board, which Mitchell was on at the time — an arrangement that is illegal in many other states.

Charters are privately run but government-funded schools that are supposed to be open to all. Policymakers and many parents have embraced charters as an alternative to poorly performing and underfunded traditional public schools. As charters have grown in popularity, an industry of management companies like Mitchell’s has sprung up to assist them.

Many of these companies are becoming political players in their states, working to shape the still-emerging set of rules charters must play by. A few, including Mitchell’s company, have aligned themselves with influential conservative groups, such as Americans for Prosperity and the Koch-supported American Legislative Exchange Council, or ALEC.

This new reality — in which businesses can run chains of public schools — has spurred questions about the role of profit in public education and whether more safeguards are needed to prevent corruption. The U.S. Department of Education has declared the relationships between charter schools and their management companies, both for-profit and nonprofit, a “current and emerging risk” for misuse of federal dollars. It is conducting a wide-ranging look at such relationships. In the last year alone, the FBI sent out subpoenas as part of an investigation into a Connecticut-based charter-management company and raided schools that are part of a New Mexico chain and a large network of charter schools spanning Illinois, Indiana and Ohio.

Two of Mitchell’s former employees told ProPublica they have been interviewed by federal investigators. Mitchell says he does not know if his schools are part of any inquiry and has not been contacted by any investigators.

To Mitchell, his schools are simply an example of the triumph of the free market. “People here think it’s unholy if you make a profit” from schools, he said in July, while attending a country-club luncheon to celebrate the legacy of free-market sage Milton Friedman.

It’s impossible to know how much Mitchell is taking home in profits from his companies. He’s fought to keep most of the financial details secret. Still, audited financial statements show that over six years, companies owned by Mitchell took in close to $20 million in revenue from his first two schools. Those records go through the middle of 2013. Mitchell has since opened two more schools.

Many in the charter-school industry say that charter schools are more accountable than traditional public schools because, as Mitchell is fond of saying, “parents can shut us down overnight. They stop bringing their kids here? We don’t get any money.”

Moreover, Mitchell said, students at his two more established schools have produced higher test scores at lower costs than those in traditional public schools: “Maybe Baker Mitchell gets a huge profit. Maybe he doesn’t get any profit. Who cares?”

But many charter supporters question that perspective. The National Association of Charter School Authorizers, a group that promotes best practices for overseeing charter schools, says schools should be independent from their contractors. Mitchell’s dual roles as both a charter-school board member and a vendor, for instance, were a blatant violation of those standards.

“This kind of conflict of interest is what I would consider shocking,” said Parker Baxter, a program director for the group.

“This isn’t as if one of the board members happens to own a chalk company where they buy chalk from, and he recused himself from buying chalk,” he said. “This is the entire management and operation of the school.”

Mitchell was pushed by North Carolina regulators to step down from his schools’ board last fall, a move he derides as unnecessary. “It’s so silly,” he told ProPublica. “Undue influence, blah blah blah.”

But concerns about his influence continued even after he stepped down. One board member resigned in frustration over the role of Mitchell’s company. Two others also quit around the same time. Mitchell still serves as secretary for the board, taking notes and doing the meeting minutes. Asked about frustrations among board members over his involvement, Mitchell said, “Everybody’s free to their own opinion.”

When charter schools were first established in the early 1990s, supporters sought flexibility and freedom from the bureaucratic rules they believed hamstrung traditional schools. Charter schools have leeway over their calendar, curriculum, and who they hire and fire. In most states, they do not have to follow many of the processes meant to prevent corruption and misspending of public dollars, such as putting contracts out for competitive bidding.

Mitchell moved to North Carolina in 1997, a year after the state passed a law allowing charter schools. He said he dreamed of starting a school after selling his computer business in Houston in 1989. He had planned on a private school, but when he moved to North Carolina and read about charters, he said he figured that was his chance. He applied to open his first school in 1999, laying out his plans to teach what his company website describes as a “classical curriculum espousing the values of traditional western civilization.” He opened Charter Day School the following year.

From the beginning, concerns about excessive profits and Mitchell’s conflicts of interest dogged the new school. In 2001, the Internal Revenue Service rejected the group’s application for tax-exempt status, noting Mitchell’s dual roles as both a board member and head of a company doing business with the board. The IRS also noted the bank account shared by the schools’ nonprofit and Mitchell’s for-profit company, and that the school was leasing space from another company owned by Mitchell.

“Mr. Mitchell thus controls both your management company and your lessor,” the IRS wrote in a denial letter. “He has dual loyalties to you and his private, for-profit companies. This is a clear conflict of interest for him.”

The school’s board — with Mitchell as a member — protested. It went back and forth with the IRS and eventually made some concessions. For example, it set a limit on the management company’s fees and required board members to recuse themselves from votes in which they had financial interests. It also sent along a letter from an independent real-estate professional who evaluated the school’s lease and offered assurances that it was at market rate. (The real-estate professional, as it happens, worked at the same firm as the board chair’s husband.)

Many of the things flagged by the IRS were left unchanged. Mitchell and an employee of his remained on the board. The joint bank account and the leasing arrangement also stayed the same. But having reached something of a compromise, the IRS approved the school as a tax-exempt nonprofit in March 2002.

Mitchell’s second school, Columbus Charter School, opened in 2007, in rural Columbus County. That school and Mitchell’s first, Charter Day School, have won recognition several years in a row for their performance on state tests.

But comparing the performance of these two schools to their traditional-school counterparts is complicated by the fact that they have comparatively low percentages of needy students, who tend to score lower on standardized tests. For instance, 37 percent of test-takers at Columbus Charter School earlier this year were “economically disadvantaged,” compared to the county’s 74 percent. The two schools do not provide busing or participate in the federal free and reduced-price lunch program — services that are considered key to ensuring broad access.

Mitchell says his third school, Douglass Academy – whose diversity was celebrated by a visit from the Koch group – is the only one that provides transportation and food for students. Its target population is children in several Wilmington housing projects. Students at the school, which opened in 2013, haven’t yet taken state tests so there’s no data to show how they’re faring.

Mitchell’s schools are also distinguished from public schools by their different tone. Staff and students pledge to avoid errors that arise from “the comfort of popular opinion and custom,” “compromise” and “over-reliance on rational argument.” Students must vow “to be obedient and loyal to those in authority, in my family, in my school, and in my community and country, So long as I shall live.”

The schools also use a rigid instructional approach in which teachers stick to a script and drill students repeatedly through call and response. Latin is taught as early as elementary school.

Mitchell’s company has managed the schools’ staffs with similar rigor. A strong sense of hierarchy took root as the schools expanded. When a new corporate office was built to house the management company, teachers jokingly began calling it the “White House.”

From the “White House,” Mitchell and other top administrators could watch teachers in their classrooms via surveillance cameras installed in every classroom, in every school. During a tour of school grounds with this reporter, Mitchell and the school’s IT director discussed surveillance software called iSpy. “We need to call it something else,” Mitchell offered with a chuckle. “Call it iHelp or something.” Mitchell said the cameras give administrators the ability to observe teachers in action and offer them tips and coaching.

As Mitchell was looking to expand his enterprise in the mid-2000s, he ran into a roadblock. North Carolina, like many states, had been cautious when it first allowed charter schools and had placed a cap on their growth.

By the time Mitchell applied in 2007 to open a charter school in Duplin County, the state was nearing that cap — and his plans fell through when the State Board of Education, deciding among three charter applicants, chose the other two schools to fill the spots remaining that year.

In 2011, they got what he wanted.

Republicans took control of the state legislature and swiftly eliminated the cap on charter schools. Mitchell was also given a coveted position on the state’s new Charter School Advisory Council, an influential committee tasked with reviewing charter applications and making recommendations to the State Board of Education.

It was a turning point for Mitchell. Over the next two years, he got the go-ahead to open two more schools. With both, he appeared to benefit from unusual exceptions or political intervention.

One of them was Douglass Academy, Mitchell’s school for needier students in downtown Wilmington. Under state law, charter schools must have at least 65 students enrolled, but Douglass Academy was well below that. Mitchell’s colleagues on the advisory council gave him a temporary waiver that allowed the school to avoid closure while it tried to boost enrollment.

“I would say it was unusual,” Joel Medley, head of the state’s Office of Charter Schools, said of the temporary waiver. According to Medley, the only other charter schools in the state that received such waivers got them on a permanent basis because of geographic isolation or because they had set out to serve special student populations deemed ill-suited to large-school settings. Neither condition was true of Douglass Academy, whose leadership blamed the enrollment troubles on difficulties securing a facility. The school has since cleared the state’s minimum, though enrollment is still far below the school’s own projections.

Mitchell’s fourth school, South Brunswick Charter School, also lucked out. In 2013, the school’s application failed an initial screening and was put in a stack of applications excluded from further consideration. But then the president of the state Senate, Sen. Phil Berger — the same Republican lawmaker who appointed Mitchell to the Charter School Advisory Council — intervened on behalf of frustrated applicants. The whole stack was re-evaluated — a “one-time decision,” said a memo from the advisory council, due to “extraneous circumstances.” Berger did not respond to a request for comment.

Even upon re-evaluation, a subcommittee of the council voiced unease about aspects of South Brunswick’s application, including “concern that two of seven board members are active employees” of its management company.

But Mitchell’s fourth school was nevertheless approved, with the stipulation that members of the management company, including Mitchell, step down from the board. South Brunswick Charter School opened its doors this summer at a temporary site. A permanent spot is in the works — on land purchased by another one of Mitchell’s for-profit companies with plans to lease it back to the school.

Mitchell’s influence has also reverberated beyond his four schools.

In 2013, the state legislature passed a sweeping charter school bill pushed by Mitchell that loosened oversight and regulation. The law relaxed requirements on how many of each charter school’s teachers had to be certified, giving schools more flexibility and potential savings on labor costs. It also included a perk — a tax exemption — for landlords who, like Mitchell, rent property to charter schools.

Parts of the bill echo legislation pushed forward in other states. ALEC, for example, has promoted legislation across the country to make it easier for non-teachers to start teaching, sidestepping what it sees as cumbersome licensing requirements. Parts of the North Carolina bill have the same wording as ALEC model legislation.

But a lobbyist for Mitchell’s group, Debbie Clary, said, “It was our bill. I was the only lobbyist working on it.” Clary added: “The person most engaged was Baker [Mitchell].”

Mitchell’s group also posted a note on Facebook after the bill was signed, calling the new law the culmination of two years of work by the Alliance. “The Alliance was able to gain an exemption from county or city property tax, no matter who owns the property, if it is used exclusively for a Charter School,” the note read.

Mitchell has close ties with Sen. Jerry Tillman, the lawmaker who sponsored the bill. “We’re good friends,” Mitchell said. “We talk.” Records show that Mitchell wrote Tillman’s campaign a $4,000 check a month after the bill was signed — the maximum that state law at the time allowed an individual to give directly to a candidate each year. Tillman did not respond to requests for comment.

Mitchell and the Alliance didn’t get everything they wanted.

Over the years Mitchell had pressed lawmakers to move charter schools largely out from under the authority of the State Board of Education. Mitchell said he views the state board as a force restricting the free market through overregulation and protecting “the monopoly of the government-run schools.”

Parents at Mitchell’s schools were urged to press their elected officials to remove charter schools from the purview of the State Board of Education: “Your legislators need to hear from you and know of your support for an independent Office of Charter Schools,” said a school newsletter. “Let them know you do not want the State Board of Education controlling charter schools.”

The 2013 bill introduced by Tillman spelled out much of what Mitchell wanted. It proposed the formation of a Charter School Advisory Board that would make all the major decisions about approving new schools and renewing or revoking existing charters without having to answer to the State Board of Education.

But the state’s other main pro-charter group deemed the proposal too extreme and came out strongly against it. An amended bill eventually passed that created a new board without all the power Mitchell and the Alliance had sought. And while Mitchell was appointed to the board, he resigned earlier this year while under pressure over conflicts of interest. He told ProPublica he stepped down because it became a lot of work.

Mitchell has also expressed frustration with a state law passed this summer that requires charter schools to comply with public records laws. Still, the new law does not apply to charter management companies such as Mitchell’s.

The board of Mitchell’s charter schools has repeatedly tangled with local news outlets that have made public records requests seeking salaries and other financial details from the schools. Last month the StarNews of Wilmington filed a lawsuit against the schools’ nonprofit board, alleging that it has violated the state public records law. (The board chair for Charter Day School, Inc., John Ferrante, did not respond to requests for comment.)

Mitchell himself has taken a hard line against disclosures of financial information concerning his for-profit companies. For private corporations, he wrote on his blog in July, “the need for transparency is superfluous” and is simply a mechanism for the media to “intrude and spin their agenda.”

In North Carolina and many other states, the battle over charters is no longer about whether to have them. Instead, it’s largely between those who believe in regulating them and creating mechanisms for public accountability and those, like Mitchell, who believe that’s the job of the free market.

“That’s the fight in North Carolina,” said Damon Circosta, executive director of the A.J. Fletcher Foundation, which sees charter schools as a way to improve public education. “That free-market ideology has taken hold with this newer legislature.”

Large national for-profit charter management companies have joined regional powers like Mitchell to lead the charge. They’ve found allies in local lawmakers. Tillman, the co-chair of North Carolina’s Senate education committee, for instance, recently berated state regulators because he was upset more schools were not being approved.

Two kinds of people get in the charter-school business, said Guckian: “Group one, they’re looking for entrepreneurial opportunities. Group two, they’re looking to run high-quality schools. My bias is toward the latter. That’s not to say I have anything against entrepreneurship, but I don’t think that’s a reason for getting into the education space.”

Gov. McCrory has tried to step in where the legislature has not. At his urging, the State Board of Education has gone beyond what the law requires and is requiring schools to submit salary information for employees of charter-management companies — numbers that Mitchell believes should be private.

“There’s no statutory basis for it,” Mitchell said of the new requirements. His schools’ board submitted basic budget documents in response to the agency’s order, but it withheld information on management-company finances, stating that the board “does not possess individual salaries paid by any private corporation that furnishes services.” Asked what he’ll do if the agency objects, Mitchell said, “We’ll see what they say and deal with it when it comes.”

He views these new requirements as a sign that North Carolina is moving in the wrong direction, toward an overregulation of charter schools. “I see the banks of the river narrowing,” he said. “In a few more years, there will just be a very narrow channel to navigate in. A lot of the freedoms will be regulated out.”

Heather Vogell contributed to this story.

If you have information about charter schools and their profits or oversight — or any other tips — email ProPublica at charters@propublica.org.

Marian Wang is a reporter for ProPublica, covering education and college debt. She has been with ProPublica since 2010, first blogging about a variety of accountability issues.

The images, along with the information, was reprinted by EmpathyEducates with the kind permission of ProPublica. We are grateful for the research, investigation, and visual illustrations.

Leave A Comment