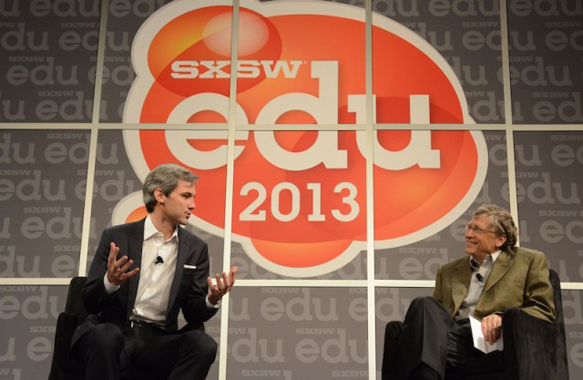

Bill Gates and Iwan Streichenberger, CEO of nonprofit inBloom Inc., discuss the potential for personalized learning technology to transform classrooms during Gates’ keynote at SXSWedu, in Austin, Texas.

Consider the course of your life. At an early age you were set on a path. When asked, “what do you want to be when you grow up?” You replied as your parents might. “I want to be a policeperson, a fireman, a doctor, a lawyer, or a teacher.” You might have dared to say I want to be President of the United States when I grow up. The answers are all admirable, and yet baffling. Why is it that when asked what we want to be we answer with what we want to do?

In the Western World we have learned that if we are to make it that means money. We do not learn it; we earn it. We earn a grade, “A,” “B,” “C,” or “D.” “D” is for dollars. “C” is for cash. “B” is the big bucks. And “A” that is the ultimate, affluence. Oh, we give lip-service to learning. We go to school…to study and become a

We attend conferences for the same reason. We want to learn, how to increase our investments, how to expand our network knowledge base. Free drinks, candy, and a show. When we were enrolled in school we called it a field-trip, now working in the field we call it a conference. Either way, there is evidence that we were and are shaped by a society that sees education as earning not learning. So should we be surprised when….

Education for Sale

t a conference made up of educators, administrators, and entrepreneurs, Bill Gates is bound to be polarizing. The mega-philanthropist, who’s put billions into education-reform initiatives like charter schools and data-mining to better evaluate teachers, is a hero to some in the education community, an enemy to others. Last week, at South by Southwest Edu—the nerdy cousin of Austin’s popular music and multimedia festival—Gates seemed to relish his role. “Software’s able to create this interactive, connective experience for the students in a way that simply isn’t economic in a public-school context,” he said at the final event of the four-day conference. Behind him, a pie chart showed a $9 billion dollar education market—a market in which technology currently has a $1 billion slice. Gates told the thousands in the audience that technology would soon make up a larger share as schools began relying on software to deliver material and provide assessments. He emphasized how software would help to collect data that would make teacher evaluations more effective and offer teachers more help by connecting them with one another. Software, it seemed, was the key to every school’s success.

Rather than take questions from the audience—which included plenty of skeptics who’d have much rather heard about proper school funding and better pay for teachers—Gates spent the second half of his hour on stage interviewing CEOs about the importance of technology. First came the head of Dreambox, a for-profit education company that offers an entire curriculum of lessons students can take on the computer, along with detailed assessments of how well students are learning a given subject. The CEO said teachers tell her that, thanks to Dreambox, “It feels like I have a classroom assistant for every child even though my district can’t afford it any more.” Next came the CEO of a charter school that offers computer dashboards for students and parents to see progress. Finally came inBloom, a non-profit company largely funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which focuses on collecting different student data and making it more usable. The latter is particularly controversial among those who worry about both privacy and an overemphasis on testing, but Gates and friends didn’t acknowledge their critics. When the session was done, some attendees cheered while others hurriedly filed out of the auditorium, ending another year’s SXSWedu.

But the event also highlights the significant challenges of showcasing a diverse array of private and public interests on education. While there are a lot of education conferences, SXSWedu is unique in bringing educators and policymakers together with tech entrepreneurs. Presumably, all sides have a vested interest in improving education, but there are deep disagreements on the role of charter schools, on teacher evaluations, and on how much we should invest in teachers, aides, and other staff. Much of the conference takes as given that technology is almost inherently positive. Jargon-y words like “innovator” and “disrupter” get thrown around constantly. But often that technology is offering a band-aid for the more disturbing problems of schools dealing with underfunding and staff shortages. Panels often highlighted high-performing charters without offering ways to incorporate technology into the classrooms most children attend in traditional public schools. Similarly, you’ll hear a lot about how technology helps teachers “make learning fun” and evaluate students beyond simply whether they get a right answer—goals many teachers might have more success with if only they had time, reasonable class sizes and weren’t being judged on test results.

However, beefing up technology offers an opportunity for profit that adding more teachers does not, and the list of sponsors in the program read like a Who’s Who of the education industry. There was Amplify, the newly rebranded version of Rupert Murdoch-owned Wireless Generation. There were Google, Lego, and the more traditional education companies like McGraw Hill, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, and mega-corporation Pearson. Many of the sponsors weren’t just in the program. Pearson’s foundation helped sponsor the opening reception, while inBloom sponsored a party. Amplify offered breakfast. The final night’s party—when the conference took over a large bar on Austin’s famous Sixth Street—was hosted by the company MyEdu and the Gates Foundation.

SXSWedu relies on these sponsorships to help defray costs, and it cultivates big-name speakers to create buzz. The trouble is, when it comes to education, corporate interests tend to align with reform-movement ideals—more charter schools, more testing, more stringent evaluations for teachers. While private business has always been a big part of education, the combined lobbying of for-profits and reform advocates can yield problematic public policy. While there’s been a backlash across the country (and particularly in Texas) against excessive reliance on testing, there aren’t many big names who oppose Gates, Duncan, and their fellow reformers besides education historian Diane Ravitch. (The festival’s executive producer, Ron Reed, told me he invited Ravitch but it didn’t work out. She was in Austin two weeks ago for a Save Texas Schools rally.) In addition to Duncan, last year also featured Marjorie Scardino, the CEO of Pearson. Together, the big names and the big sponsors give the program the feel of an industry convention for those selling and buying technology in schools—a feel that Reed says he wants to avoid.

According to Reed, attendance is split roughly into thirds—K-12 educators, post-secondary educators, and entrepreneurs. Reed imagines the event to be “a convergence zone for all the stake-holders” to discuss “topics for which there are no easy answers.”

SXSWEdu makes a concerted effort to offer a panels representing a wide array of viewpoints. Organizers allow people to propose panels and then allow anyone to vote to determine which panels make it; this year’s 175 panels came from more than 800 suggestions. The speakers represented a number of viewpoints—Allen Weeks, who heads the Save Texas Schools movement to increase funding to state public schools and decrease testing, offered a panel on how to turn around school performance through community involvement rather than reform tools like charters. There was an entire series on Texas public policy, including spirited debates on how much testing should be allowed and how best to evaluate teachers. Another presentation focused exclusively on how budget cuts by the Texas legislature had hurt public schools. Perhaps most significantly, the program included a keynote from Asenath Andrews, the principal of a charter school for pregnant teenagers in Detroit—a stark contrast to the usual examples of high-performing charters that are sold as superior alternatives to traditional public schools.

But many panels were more market-focused. Lego, inBloom, and a company called Cengage all sponsored paid-content programs. While it’s disclosed in the program, I hadn’t realized those talks were sponsored and did not arise from the voting process. The rooms for those events, as Reed points out, were at capacity. Reed says the sponsored content represented less than 10 percent of the overall festival.

Even among the regular programming, there was a heavy emphasis on the how-tos of business. For instance, one panel, titled “Business Models that Work in Education Technology,” drew a huge crowd that filled the room to capacity—outside, people waited for others to leave so they could come in. Speaking were Andrew D’Souza and Heather Hiles, from the successful education-tech companies Top Hat Monocle and Pathbrite, as well as Renata Streit Quintini, an investment specialist at a venture-capital firm. The panel was shop talk for those trying to pitch products.

The panel highlighted the advantages and disadvantages of the marketplace for getting good education tools. “Our mandate from our investors is can I make 10 times my money? This is what we’re paid to do,” said Quintini. “Do we care about leaning outcomes? Absolutely. The more you can show value of your product … the bigger the lifetime value.” D’Souza in particular argued that the high-dollar, multi-year contracts for districts and states that once dominated were no longer the only way to get a product into classrooms—a good thing. “You could close multi-year deals and not actually deliver that great of a product,” he said of the old model. Now, those looking to sell are better off marketing directly to teachers and students. D’Souza says his company launched after the sales cycle for most big schools and was headed towards failure until it began selling directly to professors. But the role of big business was still evident; when an undergrad from the University of Pennsylvania’s prestigious Wharton Business School asked about the best ways to introduce a product to potential clients, panelists pointed to distribution from big companies like McGraw Hill and Pearson.

The Google Lounge was stunning. White carpets and white walls highlighted the company’s famous primary-color scheme. Giant balls in blues, yellows, reds and greens were scattered around in case anyone wanted to do yoga. There were high-top tables with Google’s web-browser icon emblazoned on the top and giant egg chairs in the same key colors. Benches and couches were set up near power outlets. Most important, there were giant bins of candy, including full-sized Twizzlers and Rice Krispy treats.

At the front, a giant screen was framed by wood to look like a blackboard, complete with chalk and a chalkboard eraser on the ledge. The company featured 15-minute lessons throughout the day on different Google products. I’m guessing most people came for the candy, the power outlets, or the luxurious seating options, then stayed because, after all, the tools were really cool. There were the thousands lessons available on YouTube on a wide array of subjects, some for college, some for primary school, and some for people just interested in a topic. There was GooglePlus in college classes for things like office hours and teleporting guest speakers. Google Earth now lets kids track tagged sharks and look at three-dimensional versions of historic buildings. Kids can watch a “Google Hangout” from the International Space Station.

I was enjoying the candy and the Google tech. But things got a bit more complicated when the presenter explained that Google would be able to offer free virtual field trips to zoos and aquariums. From a SXSWedu perspective, that’s a great leap forward and an efficient way to deliver experiences to children. But overriding that success is a larger question: Shouldn’t we be investing enough in schools to allow kids to meet animals and sea life in person?

Even Bill Gates has to admit: Some things are best experienced in person, without the use of software.

Leave A Comment