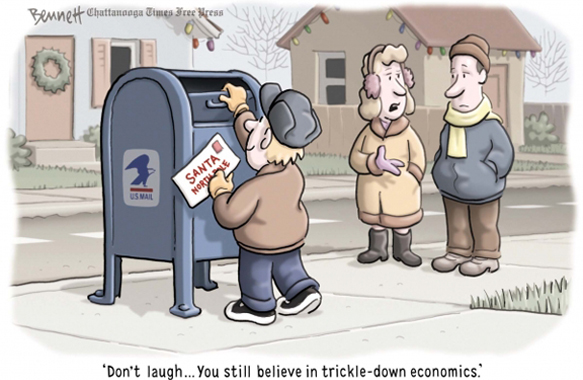

Political Cartoon; “Believe” By Clay Bennett, Washington Post Writers Group

By Paul L. Thomas, Ed.D. | Originally Published at The Becoming Radical. December 14, 2013

Compelling research suggests that the public in the U.S. is unique in its commitment to belief, often at the expense of evidence—leading me to identify the U.S. as a belief culture.

Additionally, while I remain convinced that the U.S. is a belief culture, I also argue that, below, the political cartoon posted at Truthout captures another important dynamic: Many committed to their own beliefs both do not recognize that they are committed to belief and belittle others for being committed to their beliefs:

And this brings me to advocacy for Common Core standards, with one additional point: Along with embracing belief over evidence, the public (along with political leadership) in the U.S. tends to lack historical context.

Placed in the century-plus commitment to pursuing new and supposedly higher standards for public schools, then, Common Core advocacy falls into only two possible characterizations:

1. Common Core is a response to the historical failure of all the many standards movements that have come before, and thus, the success of CC depends on CC being somehow a different and better implementation of an accountability/standards/testing paradigm.

2. CC advocacy is yet another example of finding oneself in a hole and persisting with digging despite evidence to the contrary. In other words, CC may well be yet another commitment to a reform paradigm that isn’t appropriate regardless of how it is implemented.

These two claims are themselves evidence-based (and it will be interesting to watch as others respond, as they have to my previous work on CC, by either ignoring evidence or garbling evidence to support what proves to be faith-based commitments to CC), and thus should provide a foundation upon which to continue the debate about CC.

CC advocacy and criticism are often based on false narratives and baseless claims (see Anthony Cody for one example of this problem and Ken Libby‘s Instead, we should start with an evidence-based recognition about standards-driven education reform. For example, the existence and/or quality of standards are not positively correlated with NAEP or international benchmark test data—leading Mathis (2012) to conclude about CC: “As the absence or presence of rigorous or national standards says nothing about equity, educational quality, or the provision of adequate educational services, there is no reason to expect CCSS or any other standards initiative to be an effective educational reform by itself [emphasis in original]” (p. 2 of 5). Therefore, CC advocacy has some principles within which it should continue if that advocacy is to be credible and thus effective: I am no advocate for remaining only within rational, evidence-based, and quantifiable norms for decision making, by the way, but I am convinced we must make clear distinctions between evidence and belief—and I am equally convinced that many education reformers enjoy a flawed freedom to call for evidence from their detractors while practicing faith-based reform themselves. It is the hypocrisy that bothers me, the hypocrisy of power. Let’s acknowledge that teachers currently work under the demand of measurable evidence of their impact on students while CC advocates impose faith-based policies such as CC, new generation high-stakes testing, merit pay, charter schools, value-added methods of teacher evaluation, and a growing list of commitments to education reform at least challenged if not refuted by evidence. CC advocates now bear the burden of either offering the evidence identified above or admitting they are practicing faith-based education reform.

Leave A Comment