By >P. L. Thomas, Ed.D. | Originally Published at The Becoming Radical. April 3, 2015 | Illustration Credit; AngertAesthetics (Betsy L. Angert).

The guilty verdict in the Atlanta cheating scandal seems to be a logical conclusion to the “bad” teacher myth confronted nearly five years ago by Adam Bessie.

As a 30-plus-years educator, I have daily witnessed a not-so-subtle disdain for teachers, directly as people and broadly as a profession.

One situation that captures that, I think, is the many times among my cycling group years ago when people would discover I was then an English teacher. Each time, the person would say, “I better watch what I say then”—not so jokingly.

The stereotype of the authoritarian and humorless English teacher—gray hair in a bun, red pen at the ready—is likely the image many people conjure when they think about teachers.

Not all, but many.

School for too many children is something to endure, a place that seems impossible to navigate without getting into trouble, and especially for children of color, the first confrontation with discipline and punishment that are inequitable and inevitable.

So I regret to admit that a significant reason the “bad” teacher myth works politically and there seems a great deal of glee about teachers/educators being busted for cheating is our fault—our fault each time we have created or perpetuated authoritarian schooling.

That said, I must then stress here it isn’t that simple.

I have, then, a few questions.

The first, Why are 11 educators being convicted in Atlanta, but Michelle Rhee continues to skip along scot-free?

Another, Why did professional educators commit these crimes?

And finally, What does the popular glee over these convictions reveal about justice in the U.S. as well as lingering racism and sexism?

I have some ideas about how all of these are connected.

Let me start with Rachel Aviv’s headline about the Atlanta scandal, by focusing on the subhead: Wrong Answer: In an era of high-stakes testing, a struggling school made a shocking choice.

My first idea is that there is nothing “shocking” about the cheating scandal, but that it is entirely predictable, if not reasonable.

I recommend Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale which dramatizes the consequences of “reduced circumstances.”

Adults, children, and animals backed into a corner will behave in ways that are unlike their normal behavior.

Offred/June fantasizes about murder with a knitting needle; she had been a “normal” wife and mother before the events creating the dystopia that reduces her.

Teachers/educators and students who find themselves in high-stakes situations and almost no power, then, have often and will often seek any means necessary to avoid the injustice of punishment over which that have no control.

As a high school teacher, I witnessed time and again that students who faced impossible expectations either quit or cheated, often. The problem was not the student, but the expectations and the burden of the impossible.

But here is the problem: In the U.S., we have a cultural belief that human goodness/badness is almost entirely a consequence of the individual—despite that cultural belief being mostly refuted by what research shows about the power of social forces to shape individual behavior.

I recommend in that context the research-based Scarcity: Why Having Too Little Means So Much by Sendhil Mullainathan and Eldar Shafir and the literary (as well as beautiful) The Very Persistent Gappers of Frip, written by George Saunders and wonderfully illustrated by Lane Smith (I have examined how these two works complement each other).

Let me end this by stressing that I am not calling for excusing any and all behavior because of social forces; nor am I necessarily saying that the educators convicted in the Atlanta scandal are somehow above punishment.

I do argue what the punishment should be for those educators needs careful deliberation.

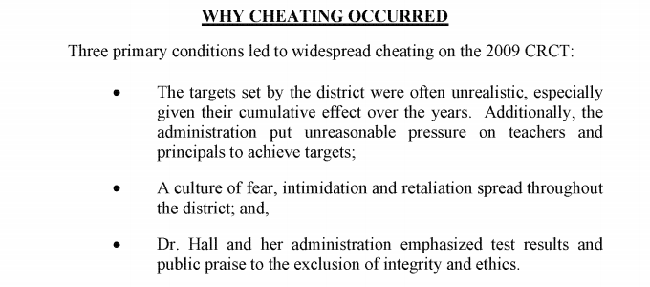

I also think the greater issue is that we must confront the reasons these cheating scandals are occurring under the high-stakes accountability mandates, which is the lesson from the Atlanta cheating scandal:

For those who think right/wrong is simple, consider that one day possessing marijuana was illegal in Colorado, for example, but the next day it wasn’t.

The solution to ending cheating among educators under the impossible weight of high-stakes accountability (just as the solution to stop student cheating in school) is to end the conditions creating it.

The Atlanta cheating scandal is not a major lesson about “bad” teachers, but it is yet another lesson about the bankrupt education reform movement, the one that made Michelle Rhee rich and famous and thus above the law (a situation that oddly seems to draw little fire from those dancing about teachers getting busted).

Particularly in high-poverty, majority-minority schools, students and teachers are living a dystopia not of fiction, but a daily experience.

“No excuses,” zero tolerance, high-stakes testing—these are the conditions that reduce good children and adults to behaviors that are unlike who they are.

High-stakes accountability must be put on trial, convicted, and sent away for life without parole.

P. L. Thomas, Associate Professor of Education (Furman University, Greenville SC), taught high school English in rural South Carolina before moving to teacher education. He is a column editor for English Journal (National Council of Teachers of English) and series editor for Critical Literacy Teaching Series: Challenging Authors and Genres (Sense Publishers), in which he authored the first volume, Challenging Genres: Comics and Graphic Novels (2010). He has served on major committees with NCTE and co-edits The South Carolina English Teacher for SCCTE

This piece was reprinted by EmpathyEducates with permission or license. We thank the Author, Paul L. Thomas, Ed.D. for his kindness and the lessons that endure.

There is so much misplaced “empathy” in this blog post, and a lot of convenient political opportunism. Empathy for convicted felons and not for the kids they robbed at a fair shot at education. Opportunism to use this event as another way to denounce accountability in public schools.

That is unfortunate.

Regardless of what the work pressures are, some people cheat and some don’t. We can say that banking regulations put bankers in bad situations, or terrible work conditions make police officers mean, or war makes soldiers snap. There might be some truth to that, but in the end, these conditions only bring out what is already in people.

Cheaters cheat. People with integrity leave Enron and blow the whistle. They refuse to compromise their integrity.

This stream of empathetic dialogue in favor of these teachers proves a point different than the one in this blog post. The public is so teacher-loving, and teachers are so teacher-loving, that there is almost no situations where people will simply say: “you did wrong.”

That’s a shame. Education is about children, not the middle-class people who serve them.