In 2013 the issue of poverty is pronounced. It is the cause of great debate and much conflict. However, the conflict is mostly in interest, self-interest. The one interest that receives far less if any attention at all is poverty and the extent of poverty. How to effectively end it is a question that few consider. The conventional wisdom is there is a safety-net which will care for the impoverished. The reality is there are holes in the net. Equally significant is the notion that we, as individuals, will never be among the poor. Actually, one in two of us already are.

Perceptions explain why most Americans do not consider themselves poor. The common belief held by 27% is the poor are lazy and I am not. Forty-three percent of Americans surveyed said they believe people living in poverty can always find a job if they really want to work. At the same time, 38 percent of Americans have requested some type of help including food or financial assistance from a charity. Thirteen

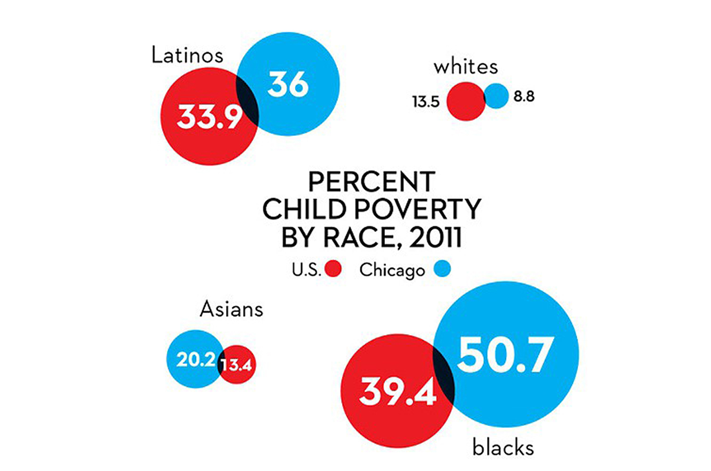

Mostly mired in self-survival, people, a large percentage of whom are the low-income working poor,have little time to attend to the poverty of others. This affects our children and their education. Not withstanding the desire, “low-income caregivers frequently do not know the names of their children’s teachers or friends. One study found that only 36 percent of low-income parents were involved in three or more school activities on a regular basis, compared with 59 percent of parents above the poverty line (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2000).” Startling as it is, for calendar year 2011 the percentage of children (persons under 18) in poverty was 21.9 percent. The total number that same year was 16.1 million.

This may be the truer silent and unseen majority. When we do catch sight of the children, poor and wealthy alike, we perceive healthy, happy, bundles of joy. Never do we imagine what we would not wish to believe exists, especially to the extent it does.

As Professor John Korsmo, PhD observed in The Journal of Educational Controversy, Poverty and Class: Discussing the Undiscussible, “Much like race, religiosity, sex, and a whole host of contrived privilege points in the U.S., poverty and class have remained for the most part don’t-go-there designations; topics that individuals, human service, and educational institutions often avoid openly discussing.” Our intentional choice not to think about, talk about, or teach the subject of socio-economic privilege associated with class dilutes efforts to eliminate poverty and ultimately, our progress in doing so. We do not associate with or support those who bear the brunt of income inequality. Conveniently and again by choice, we drive down safer roads.

The vast majority of us sit in our cars, alone. We travel on freeways, fast. Were we to slow down we would still not see what exists behind what we call sound-walls. We are sealed off and do not, cannot see the circumstances of the other, “those poor souls.” The barriers we build both literally and figuratively are large and high; best of all for policymakers they hide the truth. Black and Brown communities are ignored. The only time we attend to what occurs in these neighborhoods is when we think to convert them. Take a blighted neighborhood, expel the residents, raze the roofs, and build beauty where blight once existed. Where do we put the poor who once occupied the dilapidated homes? That is a problem we will set aside, place behind a newer wall and never wonder about again. Thus, is the situation today in Chicago 2013.

Excuses are made. Officials invested in Charter Schools and gentrification projects say “Enrollment is down. Schools are underutilized.”, Neither claim can be substantiated without skewing the numbers. Even some High-performing schools are slated for closures; however only in already neglected Black and Brown communities. Often children are being forced to travel long distances and cross gang-lines to attend a lower-performing receiving school. Mostly, the young will walk. Transportation is costly and dollars for such a luxury are scant. Parents and Principals at the “receiving schools” are perplexed and troubled. Classrooms currently in the “receiving schools” will become fuller, basically overcrowded entities. Bad as these concerns are, what is worst is the impending community effect of school closures. Lifelines will be cut!

For Tzia, a third grader who is on the student council, afternoons at the neighborhood school on Chicago’s West Side are a variety show of ballet and martial arts, hip-hop and cooking class, tutoring and fund-raisers. Five days a week, sometimes past nightfall.

Much will be lost. Mothers such as mother Shawanna Turner, 30, attended the school she now sends little Tzia to. Her family all graduated from this neighborhood school. In the communities that face school closures, generations of families came together in their neighborhood learning centers. Children found freedom and refuge, as did their parents in local public schools. Events were planned in and executed around school activities. Neighborhood businesses in the surrounding area too were invested in these institutions. Children learned. Moms and Dads took classes too. Extra-curricula activities expanded minds and supported strong bodies. From the windows of these schools the winds blew and streets were safer because of the education little learners received. Now, that solid anchor will be taken away.

Doors will be slammed shut. Windows shuttered. Building will be left to die or be demolished quickly. We, those who do not wish to see or discuss what we do or what is done in our names will remain silent. That is the American way. Do we drive by and shoot down all that supports a community?

Chicago is not alone. The difference in what occurs is only in scale. Gentrification is the complement to segregation. Segregation is the sister to poverty. Each shows up in our city schools. Essentially, this is the story of school closures and the fight for education as a human and civil right.

Gentrification. Segregation. Poverty. Each cements the certainty that children of color will be underserved in society and underserved in our schools. Education, which can be the cure, is hurt by each of these. Lets us look at the numbers, and then seek out those sweet faces, our fellow Americans who flounder because of what we have done and are doing..

Perhaps, it is past time to tear down sound and sight walls. Let us acknowledge the pervasive inequality and then, and always take action! We might begin by thinking more thoroughly about school closings, the cause and effect. Consider the circumstances in countless cities, Chicago, Philadelphia Detroit and New York…and your hometown. Is there a racial divide, a socioeconomic destabilization, and are children and education lost?

Perchance, if we ensure that education is a human and civil right we will establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, or we can settle or what is and stay silent. Please ponder the following articles and statistics. You may be surprised by what has been long blocked from view.

© copyright 2013 Betsy L. Angert BeThink

References and Resources….

- Rising Share of Americans See Conflict Between Rich and Poor. By Rich Marin. Pew Research. Social and Demographic Trends. January 11, 2012

- Report: 27% of Americans think poor are lazy, CBS News. May 16, 2012

- Perceptions of Poverty.

- Which Income Class Are You? Investopedia September 27, 2012

- Low-income Working Families; The Growing Economic Gap,. 2012-2013 By Brandon Roberts, Deborah Povich and Mark Mather. The Working Poor Families Project.

- Census shows 1 in 2 people are poor or low-income. USA Today?December 12, 2011

- US Mayors Report. U.S. Mayors. 2011

- Perceptions of Poverty The Salvation Army. 2012

- CPS Releases Enrollment Figures. WBEZ. December 4, 2012

- Closing and consolidating CPS schools – Chicago Tribune. By Frank Clark. Chicago Tribune. December 10, 2012

- Two schools show dilemma in school closing drama. By Noreen S. Ahmed-Ullah, John Chase and Bob Secter. Chicago Tribune. April 12, 2013

- Chicago School Closings May Leave Some Communities Without Old Lifelines, By The New York Times. May 22, 2013

- Information on Poverty and Income Statistics. Human Services Policy. Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- Poverty and Class: Discussing the Undiscussible, Professor John Korsmo, PhD, The Journal of Educational Controversy,

Please also consider…

Posted by Steve Bogira on 06.08.12 04:01 PM at ReaderIgnoring the misery of the poor is easy because of our separateness.

“It’s incredible that we tolerate for a minute the reality of 6 million of us living on food stamps alone,” Laura Flanders observed last week in a Nation blog post. (Nationally, the average monthly individual food stamp benefit is $134.) “I suspect it’s because we’re experiencing a new kind of segregation,” Flanders wrote. “Somehow, neither policy makers nor opinion makers seem to know enough poor people well enough to feel them, living and breathing.”

Flanders is right that segregation is central to our apathy about poverty; it isn’t really six million of us subsisting on food stamps. But segregation isn’t new, nor is it limited to policy makers and opinion makers. It’s a way of life, in Chicago and many big cities. As we showed last year, most of our city’s African-Americans still live in 21 community areas whose aggregate population is a stunning 96 percent black. The vast majority of Chicago’s high-poverty census tracts are in these areas.

Then there’s our public school system. To look at the percentage of white kids in Chicago’s public schools you’d never know that the city is 45 percent white. The racial segregation of our schools is economic segregation as well: 87 percent of the students in the public schools are from low-income families. With such a concentration of poverty in classrooms, trying to solve the schools’ problems with a longer day or more rigorous testing is naive.

We’re also segregated, racially and economically, where most of us work. And our residential and economic separateness lead quite naturally to segregation when we eat out, and go to movies, plays, concerts, and ball games. White people often don’t even notice how pervasive segregation is, since, for the most part, we’re not the ones being harmed by it.

Becoming aware of how segregated we are won’t by itself change things. But it’s a necessary first step.

Chicago’s growing racial gap in child poverty Posted by Steve Bogira on 10.04.12 10:23 AM at Reader

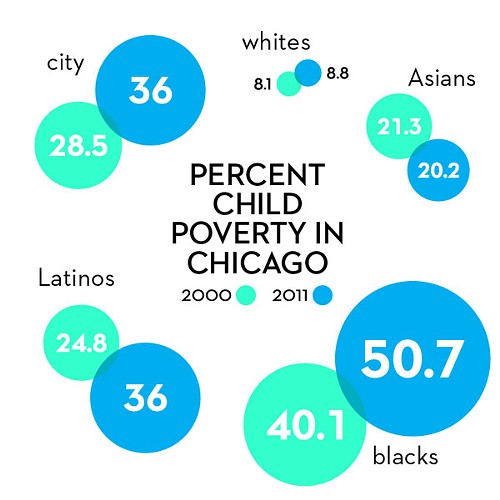

More than one in three Chicago children are living in poverty, according to newly published census data. But a closer look at those figures shows that “one in three” hides a striking inequality.

Fewer than one in 11 white kids here are living in poverty—compared with more than one in two black kids.

The news regarding white Chicago kids, in fact, is good: their poverty rate is significantly lower than the national rate for white kids. But for black, Asian, and Hispanic children, the poverty incidence is higher in Chicago than for their counterparts nationally:

- Children 17 and younger. Data from American Community Survey, U.S. Census Bureau, analyzed by Social IMPACT Research Center at Heartland Alliance

Moreover, the racial gap in child poverty in Chicago appears to be growing:

Leave A Comment