Public defenders know that the trouble with our justice system extends far beyond abusive policing.

One has to admire the way we, as a country, have paid tribute to the lives of Rafael Ramos and Wenijan Liu, the two New York police officers shot to death while sitting in their police cruiser. We have rallied to support their families across ideological lines, demanding that they be remembered with dignity and honor.

But, juxtaposed against continued protests over police mistreatment of black men, they also help to highlight the fact that other lives are not valued at all.

Michael Brown was left dead in the street for four hours after being shot by a Ferguson, Missouri, police officer. Eric Garner lay dying on a sidewalk after being choked in Staten Island, surrounded by the NYPD police officers who exhibited no sense of urgency to help him. Tamir Rice, a 12-year-old boy, was playing with a toy gun when he was shot dead less than two seconds after being confronted by a Cleveland police officer.

Rather than unifying in similar grief over these deaths, news outlets helped to justify the killings by dehumanizing the victims. We learned that Brown had been in a scuffle once, that he dabbled in drugs and that he may have stolen some cigars earlier on the day of his death. We were told that Garner had a history of selling untaxed cigarettes on the street and that he was out on bail at the time of his death. And while Rice was too young to have amassed any documented life-mistakes, the media wasted no time letting us know that his father had a history of domestic violence.

Of course, none of this information had anything to do with the actions of police. While we would rightfully have been disgusted at the media’s attempt to dig up minor transgressions slain officers Ramos and Liu may have committed, we tolerated this reporting because it fit into our accepted narrative that some lives are less valuable than others.

The closing weeks of 2014 saw grand juries refuse to indict Officer Darren Wilson for shooting Brown and Officer Daniel Pantaleo for choking Garner to death. These decisions stirred the nation. Some, viewing them in isolation, demanded the two officers be punished as justice for the families. Others, focusing more broadly on police abuse against black men and boys, demanded an end to unlawful use of force by law enforcement. They demanded video cameras on police, civilian-review boards, and federal investigations of local police shootings. They demanded that police departments demilitarize and stop treating the communities they police as the enemy.

But these verdicts underscore not just how people of color are treated by the police but an entire system that monitors, arrests, prosecutes and incarcerates Americans based on class and race. The vast majority of poor people and people of color whose lives have been lost to this inhumane system are never shot or beaten by police. They are not victims of unlawful abuse that can be caught on camera or ferreted out through federal investigation. They are victims of a lawful system of mass incarceration.

As president of Gideon’s Promise, an organization that works with public defenders who represent our nation’s most marginalized populations, I understand that for every police shooting, tens of thousands of lives will be destroyed by a legal process that wreaks far more havoc on our most vulnerable communities than the illegal use of excessive force by police. So too, do the lawyers who represent these communities.

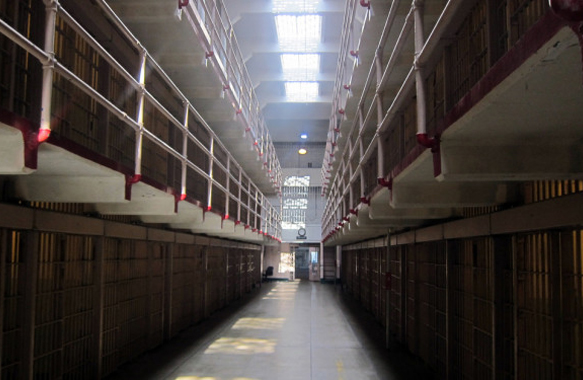

We have accepted a criminal-justice narrative that lumps the world into categories of villains and heroes. Police and prosecutors are good guys in white hats. The communities they police—particularly poor and minority communities—are presumed dangerous. It is this dehumanization that lulls us into complacency, suppressing our outrage over the fact that 2.2 million, almost exclusively poor people are warehoused in conditions so deplorable that some would rather die than live in them (consider the sixty-day hunger strike last year at Pelican Bay State Prison protesting inhumane living conditions). It allows us to remain blind to the fact that the vast majority of people in the criminal-justice system are processed from arrest to conviction with only an overwhelmed and under resourced public defender to try to get them justice. It enables us to accept a system which disproportionately punishes people based on race. It enables us to become completely detached from the people and families destroyed by our indifference, and to accept “tough on crime” policies that destroy America’s most vulnerable communities.

In the days following the grand jury’s decision not to indict Officer Wilson in Ferguson, public defenders discussed the disparity in the way we treat lives deemed disposable and those we do not. In one of the more poignant posts, a young public defender suggested that her colleagues across the country begin to file pleadings titled, “Motion to be Given the Same Treatment and Protections as White Police Officers.”

After these officers killed men they were presumed by the system to be innocent. They were allowed to live their lives as the system investigated the deaths. While the communities mourned the loss of loved ones murdered by police, these officers were free to carry on. Wilson was even able to marry.

These cases were presented to grand juries by empathetic prosecutors. Because we have the transcripts in Wilson’s case, we know the prosecutor, whose own father was a police officer who was shot and killed by a black man, elected to share exculpatory evidence with the grand jury, to allow the officer to testify without challenging his account through cross examination, to aggressively question the reliability of witnesses who inculpated Wilson, and to provide the grand jury with instructions that were as favorable to Wilson as possible. In short, these police officers were treated by the system as valuable lives worthy of every possible protection.

Our nation’s public defenders, who represent the majority of people accused of felonies—roughly 80 percent of all those accused of a crime rely on the services of public defenders—know that their clients cannot expect the same treatment from the system. Once the barest of accusations is levied, they are arrested and locked up. A bond is set that they cannot make. They sit in jail during the investigatory phase, often losing their jobs and their homes. Not only are they not free to get married, they are unable to even touch or hold their loved ones.

When the prosecutor brings the case before the grand jury, only evidence of guilt is presented—it is not challenged, or even questioned. The prosecutor does not tell the grand jury about possible defenses. The indictment is virtually automatic. In fact, in the last year for which data is available, in more than 162,500 cases prosecuted by federal prosecutors, the grand jury failed to return an indictment in only eleven. Regardless of the outcome of these cases, the process itself routinely destroys poor people’s lives.

Every commentator familiar with the criminal-justice system that I have read, regardless of his or her view of this case, recognizes that if these prosecutors wanted to get indictments and leave the decision to a jury at trial, they certainly could have. But they chose not to. Under the most flattering interpretation, it is because the prosecutor respected the dignity of these officers’ lives, valued their liberty, and used his or her tremendous discretion to prevent these cases from going to trial.

A favorite bumper sticker of mine reads, “If you’re not outraged, you are not paying attention.” I am a fan of outrage and outraged people. But for most of us, outrage comes in short, intense bursts, when well-publicized travesties of justice make it impossible to look the other way. Our outrage usually focuses on isolated instances, detached from a broader analysis. It burns hot for a brief period of time, but rarely result in lasting change.

Ferguson and Staten Island are certainly among those outrage-invoking moments in our history. But if we are to capitalize on this moment to drive meaningful change, we will need to find a way to keep the national outrage burning.

The battle for equal justice will only be won when we demand equal treatment in every aspect of our justice system. We must muster outrage over the routine dehumanization that happens in our criminal-justice system, rather than reserve it for the most extraordinary instances of injustice, if we are to maintain a movement for change. That is why I have appreciated the contribution our public defenders have made to the national discourse. The voice of these activists helps us see the events in Ferguson and Staten Island in a broader context. It helps us understand that they are the result of the accepted dehumanization of marginalized people at every stage of the justice system. It is a necessary voice if we are to find a way to have the sustained outrage necessary to drive meaningful change in 2015. For if we only see these events as about the men who are killed, or about illegal police abuse, it will not be long before the issue fades from our social media feeds and is replaced by ever more gossip about Kim Kardashian and invitations to play Candy Crush.

Jonathan Rapping is president and founder of Gideon’s Promise, an organization dedicated to building a movement of public defenders to transform criminal justice in our nation’s most broken systems. He is also an associate professor and the director of the Honors Program in Criminal Justice at Atlanta’s John Marshall Law School. He was named a 2014 MacArthur Fellow for his transformative work on criminal-justice reform.

This piece was reprinted by EmpathyEducates with permission or license. We thank the Author, Jonathan Rapping and The Nation for their kindness. We are grateful for the observations, research and what we believe is a vital conversation.

Leave A Comment