Thanksgiving at the Brown house, with family, friends, ham hocks, a little football, and an empty chair.

Brown’s house is an ordinary ranch in a pleasant, safe neighborhood a few miles from where his son was killed, completely average except for one thing—down in the man cave the walls are decorated with photos of Brown’s dead son, a tapestry of his dead son, a photo of a mural dedicated to his dead son. Hanging on the corner of the TV is a black necktie with his dead son’s face peeking out at the very bottom, like a bit of sun under a long black cloud. Brown leans against a pillow bearing his dead son’s face. Mike-Mike, they called him, as if saying his name once weren’t enough to express their love.

Brown is a tall, powerfully built man with a shaved head and a handsome face that seems perpetually solemn. In the months since his son died, he’s stopped cutting his beard, which makes him look like a figure from the Old Testament. As always, he’s wearing a T-shirt bearing his dead son’s face. He just got back from an overnight trip to New York, where he did five TV interviews in one day, and he looks exhausted but also relieved. The tension is over, the faint hope of a conviction extinguished, and now the real struggle begins. He leans back into the sofa and tries to relax, tapping ashes from a Newport into a red plastic cup.

Painting by Tim O’Brien

Brown is thirty-seven, but in the months since his son was killed he has stopped cutting his beard and seems much older.

Downstairs, the men make a real effort to focus on the game, but in the absence of women and children the conversation turns to the big subject: the protests all across the country, the gratifyingly widespread criticism of the prosecutor and his tactics, the news coming out about how the Ferguson authorities bungled the crime-scene investigation by failing to measure the distance between shooter and victim, failing to record the first interview with the officer, failing to take his gun away at the scene, failing to prevent him from washing his hands, the medical examiner who couldn’t be bothered to replace a dead camera battery—a series of errors so relentless it’s hard to believe they weren’t screwing up things on purpose.

And the thing his son’s killer said about feeling like a five-year-old fighting Hulk Hogan? “He was six four,” Brown says. “So now they’re saying Mike-Mike was six six. He was six four. Just had a little more weight on him, and most of it was flab.”

Kids run in and out, and the men change the subject. Cal’s mom comes down to smoke a cigarette, taking off a shoe to rub her foot over her tiny toy poodle. Brown goes upstairs and comes back with his baby daughter on his arm, dressed in a holiday dress and pretty shoes. He props her on the cushion and she stares ahead with a sleepy, solemn face. Then Rev. DeVes Toon of Al Sharpton’s National Action Network arrives with an uncle of Oscar Grant’s—the man whose death at the hands of a California police officer was memorialized in the movie Fruitvale Station—and he describes his latest idea for a publicity campaign: pictures of families at their Thanksgiving tables with one seat empty, propping up a picture of their lost child. “You gotta keep the heat on them,” he says. Through peaceful means, he adds, although he believes the officer who killed his nephew never would have been convicted if not for the riots that followed his death. “In the back of their minds, they gotta smell the smoke. You know what I’m saying?”

Brown listens but doesn’t respond. Soon the conversation shifts to yesterday’s interviews. Of course they all wanted to know how it feels. The lawyers have been telling him to open up, so that’s what he tried to do. But some of it’s just weird, like pretending to walk down the hall so they can get some B-roll footage.

“Like acting?”

He laughs. “That’s what I’ve been doing for the last three months—acting, acting, acting.”

Here, with his family and friends, he seems almost like a different person—quiet as usual, but less so, comfortable in his den, the regular guy he was before his life became a public nightmare.

Brown runs out to his car, with Cal chasing after him. He’s sure it’s a mistake—it has to be a mistake. He and Cal just got married three weeks ago and Michael was his best man, grinning nonstop in his rented suit. How could he be dead?

Ten awful minutes in a hot metal box. As they approach the shooting site, traffic blocks their way. They leave the car and run. Another car door flies open and out jumps Michael’s mother, Lesley McSpadden. On Canfield Drive, where a housing complex begins, a series of modest two-story apartment buildings, they see police cars and yellow tape and a growing crowd.

In the middle of the street, a body lies covered by a sheet. Brown scans the crowd and Michael isn’t there, and people tell him that really is his body under the sheet. But a voice in his head keeps saying, No, that’s not him. Can’t be true.

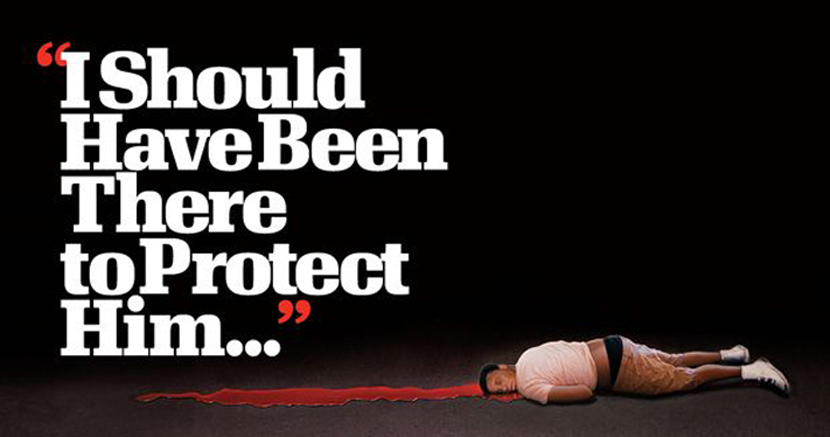

He just cannot take it in. His mind pushes it away. I should have been there to protect him, he thinks. The time the cop asked for Michael’s ID when he was standing on the front porch, when he was ten years old and so big he already looked like a man, Brown told the officer, “Officer, that boy is a minor, so you better talk to me.” When Michael was sixteen, they had the talk about being cooperative with police. “It’s not a bow-down thing,” Brown said. “They just have things they have to do.” And just a few months ago, his son told him the police were always messing with people on Canfield, saying stuff as they walked down the street. Brown said, “Well, what do you say back?” Michael said, “Nothing. I just keep walking.”

Brown goes up to a police officer and tells him he’s the father, asking if he can identify the body—he has to see it with his own eyes. He’s talking as calmly as he can. But the officer tells him to step back, someone will come talk to him in a little while.

In the heat and humidity of August, the afternoon sun burning down, they stand waiting. Nobody comes to talk to them. Other family members start showing up, cousins and uncles and grandparents. In a daze, one uncle crosses the yellow line to try to get a better look and the police stop him. Word starts going through the crowd: Those are the parents. People begin coming up to them and saying their son had his hands up when he was shot. A nurse tells them she heard the gunshots and ran over to help him, but the police told her to stay back. Later, it will come out that a paramedic already had declared him dead, but since nobody bothers to tell them, they’re standing there thinking the cops refused medical help and just let him die.

Hysterical now, McSpadden starts screaming at the cops, the media, and even—as Brown remembers it later—at Cal. She’s not the mother. What does she need to be out here for? Grief takes many forms, not all of them pretty. Brown pulls Cal away. His eyes stay fixed on the white sheet. The red patch around the head seems to keep spreading and spreading.

Brown is an internal person, the kind of man who takes things in and contains them until they can be tolerated. His mother is so religious she allowed only gospel music in the house. His father was a soldier who came back from Vietnam intact and worked hard and ran five miles every morning. After some rough years when he was younger—seventeen when he got McSpadden pregnant, he veered between work and street life—he started going back to church. He got a GED, drove trucks, worked construction. Now he has a steady job transporting patients in a medical van. But there’s no doubt in his mind that his son has been executed, nor much doubt in the crowd around him. Everyone knows at least a few names from the long list of young black men killed in dubious police shootings: Sean Bell, Amadou Diallou, Kimani Gray, Patrick Dorismond. Just in the last few months, police killed a man who was selling loose cigarettes on Staten Island and a young man who was looking at an air rifle in an Ohio Walmart. And many of them have been harassed as well. St. Louis is one of the most segregated cities in America, much of it the result of city policies, like its 1916 “segregation ordinance,” the first such referendum in the nation.

In 1917, a white riot killed more than forty-eight people, including a baby, thrown into a fire. In 1949, when black kids were first allowed into public swimming pools, whites rioted again. And these little Missouri towns are notorious for financing their city governments with the traffic stops of poor black people—last year, Ferguson issued thirty-three thousand minor-crime arrest warrants for a population of twenty-one thousand, mostly for traffic violations and overwhelmingly to black residents. (At 29 percent of the population, whites get stopped just 12.7 percent of the time.) In the nearby town of Bel-Ridge, a traffic light was even rigged so police could change it as people entered the intersection, boosting their city budget by 16 percent. Here on Canfield, one of the roughest neighborhoods in town, the level of trust is zero.

Brown watches the cops closely, afraid they might plant a gun to justify the shooting, and sure enough, a rumor soon roils the crowd: They’re saying Michael had a gun.

An hour and a half after the shooting, detectives finally arrive.

After two hours, shots go off in the distance—everyone hears them—and the police bare their weapons to the crowd, telling them to get the fuck back and calm the fuck down. They’re obviously nervous, but what strikes Brown is that they turned their guns on the crowd instead of in the direction of the gunshots. They fear us. Then they bring out a line of police dogs to force the people back and Brown glances at his baby daughter, sitting on a little hill with his mother-in-law, and sees a police dog a few feet away from her, snapping furiously. An officer sees what’s happening and tells the K-9 cops to leave the family alone, but the only bit of real kindness they remember that whole day is when the police pass out bottles of cold water among themselves and one officer—not from Ferguson—refuses because they didn’t offer any to the family. He tells them what’s happening isn’t right but he has to do his job. Tell your husband to get a good lawyer, he says.

For another couple hours, the police leave the body lying in the street. Half the neighborhood is standing there without fear. A nearby TV crew calmly documents McSpadden’s grief—“You took my son away from me! You know how hard it was for me to get him to stay in school and graduate? You know how many black men graduate?”—but the trained professionals with guns and dogs are too afraid to remove the body.

Finally, the transport van pulls up, and that’s when they lift the sheet for one of the cousins to see. She comes up to Brown and says it’s really him. He cries out and falls to his knees.

“We spent four hours and thirty-two minutes watching him lay on the ground,” Cal says later.

“On the hot ground,” Brown says.

“And you could just see all the blood. Every time you looked at the sheet, it was more and more blood.”

Brown looks up. “That was the most hardest thing I ever been through in life,” he says in a voice that still seems stunned, so soft and distant it could be coming from inside a safe at the bottom of a river. “We was treated like we wasn’t parents, you know? That’s what I didn’t understand. They sicced dogs on us. They wouldn’t let us identify his body. They pulled guns on us.”

To him, it seems like the police were trying to aggravate the crowd on purpose so they could cover up what really happened.

Brown and his wife, Calvina, with daughter Mi’kelle at Mike-Mike’s funeral, August 25. Opposite page, brown and his son (left) and cousin Chris Tallie at Mi’kelle’s first birthday party last year.

Crump is at church when his phone starts blowing up, one call after another—including a call from Tracy Martin, Trayvon’s father. “Crump! They need you in St. Louis! They killed this kid and they left his body layin’ in the street!” The most prominent civil-rights lawyer of his generation, Crump gets at least fifty calls like this every week. Currently, his clients include the victims of a series of “Houdini-handcuff suicide killings,” in which brown boys were handcuffed in the back of the police car and police claim they committed suicide: Victor White in Louisiana, Chavis Carter in Arkansas. Also Alesia Thomas of Los Angeles, a black woman who died after a police officer kicked her seven times in the crotch—there’s a video the court will not release for fear of another Rodney King riot. But like everyone else, he’s shocked by the stark fact of the bodily desecration: that boy lying for four and a half hours in the street. He books a plane.

That morning, Brown huddles with Cal and their kids and various relatives, trying to be strong for them and doing his containment thing, packing the feelings down. He stays very quiet. He still cannot fully believe that was his son under the sheet. He’s always been “mushy” with the kids, Cal says, but today it’s like he’s trying to hug them safe, taking comfort from the role of the protector. Later, he drops by a local radio station with Pastor Carlton Lee, a lively young preacher whose church he recently joined, still so stunned he seems to Lee “almost like a zombie.” Lee tells him, “You have my support, we love you,” and Brown answers, “Thank you. I need it. Pray for me.” Then he goes on the radio and asks everybody to stay peaceful.

The McSpadden side of the family spends the morning at Aunt Des’s house, talking obsessively about what happened. How did you find out about it? What did you hear? He had just graduated! He wasn’t a bad kid! He wasn’t a kid who was constantly being arrested and put in jail. He wasn’t that kid! They are a family of ministers and workers. One uncle built a school in South Africa. One cousin works as a sales executive at AT&T. McSpadden worked behind a deli counter for ten years, rising to supervisor. But most of them have been hassled by police. A cousin named Eric Davis remembers the time he brought some white friends home from college, telling them to bring their college IDs because they would get pulled over—and sure enough, just as they were pulling into town, they got pulled over. His friends were astounded. Even mild-mannered Charles Ewing, a God-fearing pastor of forty years, was arrested on a mistaken charge, and the cops handcuffed him and left his sister by the side of the road. That was just one town over in Jennings, where the entire police department got disbanded a few years ago because of all the harassment.

Downtown that same morning, St. Louis County police chief Jon Belmar tells the press Brown physically assaulted the police officer who shot him. But he doesn’t name the police officer, who has been placed on administrative leave with full pay.

That afternoon, the two families come together for a prayer vigil at the shooting site. A memorial of teddy bears has appeared on the fatal spot. McSpadden lays out a line of red roses and Uncle Charles says a prayer and praises all the young men and women who have gathered in peace to honor their dead brother. “The world needs to see we can come together, do it peaceably, and pray.”

A police car drives past, crushing the roses. That night, the riots start.

“You gotta fight for his legacy now,” Crump tells him. “That’s your fight. Nothing else.”

Brown shakes his head and says nothing. He’s not an activist. He just wants to see the killer punished.

Crump has been here before. He was in fourth grade when he moved to an integrated school because of someone named Thurgood Marshall and began his long climb from rural poverty to law school. He starts talking about the journey to justice, the support of civil-rights groups, the legal steps, and public campaigns. He puts Brown on the phone with Tracy Martin and Ron Davis, the father of the Georgia teenager who was shot to death for refusing to turn down his car radio. “You can’t give way to emotions,” he tells them. “You can’t get justice by going to be unjust.”

Sharpton arrives on Tuesday. Brown’s still angry and locked in his underwater safe, and McSpadden still can’t stop crying, but both of them are now ready to make another public call for peace. Sharpton is pleased. Some families don’t know the difference between Eric Holder and Eric Clapton, but they get it—they don’t want the police to be able to say Look at what I was dealing with. I had to shoot.

Before they leave, Sharpton has one warning for them: “They gonna go after your son. Then they coming after y’all. I’ve seen this playbook. Get ready for that.”

“Going out to eat, just taking rides.”

“Sitting around, watching a movie.”

“Cooking dinner at home.”

“Playing games. Barbecues.”

“We would give him a mask, let him scare the kids,” Brown says.

“Playing the dozens, where you just go back and forth, talking about each other.”

Girlfriends? They flocked to him. He had that laid-back demeanor where you wouldn’t know if he was interested. “But he had one particular girl that I feel like stole his heart,” Cal says.

“She still come around,” Brown says. “And she’s in college.”

“She has her head on straight. She’s going to school for forensic science. And I can actually say that he loved her, because I remember one time they were not talking and I gave him a few little pointers. And he said, ‘Cal, I love her. She gonna be my wife.’ ”

Brown nods, pleased. “He flirted around. But the person that he’d bring to the house, it’d be her. He didn’t ever bring anybody different to the house.”

Cal gets a big smile on her face. “You ain’t tell him about how he was a prankster.”

Brown shakes his head. “He called me . . .

“April Fool’s.”

“April Fool’s Day. He called me and said, ‘Look, I didn’t want to tell you, but . . . Shae’s pregnant.’ And I said, ‘What?’ ”

“No,” Cal says, “You’re gonna be a grandfather.”

“Yeah! That’s what he said. ‘You’re gonna be a grandfather.’ And I said, ‘What?’ He said, ‘I knew you was gonna sound like that. I’m gonna call you right back.’ ”

He let them stew all day. They were steamed, eight kids in the house already, saying, “How are we going to take on another kid? They both gotta go to school! We gonna have to take care of this baby!”

He finally called back around ten that night and said, “I’m just playin’. It’s April Fool’s.” Brown hung up on him.

'Do I forgive Darren Wilson.'

'Babe, you were supposed to say Yes.'

'I did.'

Do you?'

'No.'

Cal laughs and Brown clarifies.

'His actions, what he chose. Might actually be a good guy, just had a bad day.'

But there are fresh outrages every day: the Ferguson police refusing to wear their name badges, shooting a female preacher with a rubber bullet, roughing up reporters, handcuffing a ninety-year-old Holocaust survivor, wearing I AM DARREN WILSON wristbands, tear-gassing people standing peacefully in their own yards. When they finally release an incident report, it contains nothing but the date, time, and location. Violating both the law and their own policies, it includes no narrative of the event.

On Wednesday, Ferguson police chief Thomas Jackson tells the media that their son hit the officer in the face so hard he had to go to the hospital—another insult, like he’s already building a case against their son and won’t hesitate to make false claims to do it.

That night, the violence flares again—and again the militarized reaction of the Ferguson police shocks the world.

On Thursday, the governor turns the police response over to a black Highway Patrol captain named Ron Johnson, who marches with protesters and changes the tone completely—suddenly there’s music and free food. But the very next day, Jackson releases a video of Michael stealing cigarillos from a convenience store and shoving a clerk who tried to stop him—a decision denounced by the governor and opposed by the Justice Department. To the family, it feels like another desecration. Even if he did such a thing, did he deserve to be killed for it? The violence flares again.

When prosecutor Bob McCulloch refuses to allow a special prosecutor and takes the case to a grand jury, another blast of indignation rises. In Ferguson, McCulloch is infamous for defending a group of policemen who gunned down two unarmed robbery suspects at a Jack in the Box, dismissing the victims as “bums.” And everyone knows his father was a policeman killed by a black suspect. Even the St. Louis county executive called him biased. This is the impartial hand of justice?

Pastor Lee keeps bringing back reports from the protests—each time he talked the protesters into taking a couple steps back, the police took a couple steps forward. He got a call about possible vandalism at his church, and while he was driving there they pointed an M16 at his windshield and touched a gun barrel to his wife’s head. He was there when they rushed the Holocaust survivor. He got shot at with rubber bullets. He was standing next to the crew from Al Jazeera TV when the police lobbed a can of tear gas at them. They ran with their eyes burning and the Al Jazeera guy said, “I feel like I’m back in Palestine.”

Endlessly, they parse the crime. Dorian Johnson, the kid who was with Michael that day, said that the officer passed them and told them to “get the fuck on the sidewalk.” They kept walking. He squealed his tires backing up and grabbed Michael by the throat. Dorian said that the cop’s gun was already drawn and he told Michael, “I’ll shoot.” Michael was wearing a T-shirt, shorts, and flip-flops, nowhere to hide a gun. Why did he have to shoot him?

Other witnesses tell different stories, and it’s unlikely the truth of what happened will ever be certain. But there are larger truths. At his church, Brown pleads: “Pastor Lee, you know he’s not a thug.”

Finally, they usher him past flashing cameras to the stage. He looks out at the world with that thousand-yard stare, thanks them for the love and support, and asks for peace. “Will you please, please take a day of silence so I can—so we can lay our son to rest. Please. That’s all I ask.” They lead him back down into the flashing cameras, and the reporters rush him.

Then it’s the funeral, another mob scene, 50 uncles and aunts and cousins and another 550 friends and a few thousand strangers, politicians, and celebrities, the TV cameras bristling from an elevated duck-blind across the street and camera crews stalking the crowds. Backstage, they get into a squabble about the lineup—why are so many politicians scheduled to speak? The band vamps for long stretches. Finally they file in, McSpadden touching a handkerchief to her nose, Brown numb and staring. The band breaks into a boisterous spiritual.

To Brown, it’s all a blur. There are words about the Prince of Peace and what happens when the wicked advance, for we are accounted as sheep for the slaughter, and periodically the music rises and voices cry out and then an uncle named Bernard is up there in dark glasses saying that he’d be lying if he said he didn’t still have anger in his heart and revenge on his mind. “But I can’t be no fool. We got to do it the right way.” A cousin talks about God and freedom and equality and there’s more music—he saw the best in me when everyone else around could see only the worst in me—and more sermons and Pastor Charles talking Cain and Abel, and Cain’s blood is crying from the ground just like Michael’s blood is crying from the ground. Crump talks about Dred Scott, and Sharpton brings the congregation to their feet with a mixture of calls to activism and the striver’s sermon heard weekly in every black church in the land: “Blackness has never been about being a gangster or a thug. Blackness was about no matter how low we was pushed down, we rose up anyhow.”

But Brown hears none of this. Too emotional to speak himself, he lets Cal speak for him. She says what she’s been telling him privately, trying to stop him from blaming himself: Michael was a kind and gentle soul who was chosen by God to bring change to America. “We have had enough of seeing our brothers and sisters killed in the street,” she says. “We have had enough of this senseless killing. Show up at the voting polls, let your voices be heard.”

Then they file out and there’s a crowd of thousands pressing against the barriers, TV cameras mobbing the hearse, the heat 100 degrees. One woman shudders to her knees in a pouring sweat. A young man in dreadlocks gets mad because he got kicked out of the inner circle behind the barricades, where Spike Lee and other celebrities mingle with the dazed family members. He wants to know why the protesters aren’t given a place of honor. “The media didn’t come because of Michael’s blood,” he shouts. “They came because of what we did!”

At the cemetery, women carry umbrellas, the men sweat in their black suits. A man sings a spiritual about going home, a small choir sings “I’ll Fly Away.” The casket arrives in a white carriage and only then, when the box is actually being lowered into the ground, does the spell on Brown finally break. His son is dead and he can be silent no more. He cries out and throws his head back, his face a mask of unimaginable agony.

“Did it upset you that he was left out for so long?”

“Yes.”

“Is that something that still upsets you?”

“Yes.”

Afterward, Cal has a talk with him. She’s been sticking to hugs and prayers, but now something must be said. “You’re portraying yourself as an angry black man,” she says.

“But I am angry,” he answers.

“I know that you are, but if you’re calling for the supporters and the protesters to be peaceful, you gotta have a better look. You can’t call for peace looking like you want to hurt somebody.”

The problem is he does. One of the reasons he’s so fierce on the subject of peace is to remind himself.

He takes comfort from the support of the community. One of Michael’s teachers even wrote a letter saying Michael was one of the kindest kids she ever taught, quiet and funny, his parents “fiercely protective” and “active in every aspect of his education.” Things like that help take the sting out of the horrible glee in the right-wing media over the cigarillo video, mocking the family’s “rush to judgment” about the police as they themselves rushed to judge. Maybe he was high on angel dust? Didn’t he hit Officer Darren Wilson so hard he had a “blowout fracture to the eye socket”? And what about that “thug music” he made? Over and over, they linked Brown’s death to the president, whom they accused of “orchestrating” the protests and dividing the country by race. Sample comment: “What holiday isn’t celebrated in Ferguson? Father’s Day. It’s too confusing for them.”

Then another terrible thing happens. The split between Brown and McSpadden was very bitter, with fights over child support and parental responsibilities, and all that history erupts when McSpadden sees Cal’s mother selling Michael Brown T-shirts on West Florrisant and explodes into rage. With a group of friends and her husband, Louis Head, they swarm the T-shirt stand, taking the shirts and all the proceeds, too. Someone attacks Cal’s mother’s boyfriend with a pipe—exposing, in their grief and rage, the divided family’s deepest troubles.

Brown starts asking Pastor Lee about the Bible. Why would God send his only begotten son to die? What was the point of that? Why would he send his son down to be a sacrifice?

A young man with an even younger face—on cold nights at the protests, he wears one of those Tibetan hats with earflaps and strings hanging down—Lee was stopped by the police so often as a teenager he would leave the house ten minutes early to accommodate. There’s no doubt in his mind about the overall justice of the cause. After the killing, he even signed on as NAN’s local representative. The result has been at least sixty-nine death threats from right-wing racists, including at least one that said they would burn down his church with him in it.

His answer to Brown: “What if Mike Jr. could be the equivalent of Saint Paul? What if Michael Brown Jr. is the justice martyr for us to take the injusticeness that the black man is going through all the way around the world, to expose how people are being treated?”

Inspired, he starts writing a sermon called “Arrest Them Now”: Prosecutor McCulloch decided to take the case to a grand jury rather than bring charges himself, so he’s like Pontius Pilate washing his hands. The Sadducees and the Pharisees were the police chiefs who incited the people and Barabbas was Darren Wilson. When he delivers the sermon in church, Brown is sitting in the audience. “Which one do you want us to crucify? Do you want us to crucify the murderer? Or do you want us to crucify the innocent person? Kill Michael Brown and let the murderer go free?”

Brown tears up.

But when he’s finally able to talk, he comes prepared to tell the sad as well as the good.

His size was a problem. Kids teased him, calling him fat, and one day he said he didn’t want to go back to that school. “I told him, ‘They’re just kids that play jokes and don’t know that they’re hurtful jokes at that age. Why don’t you laugh with them?’ ”

Brown’s father died when Michael was eight, which hit the boy hard because they were close. He started asking questions about life then, and Brown had to tell his son that there were things you just couldn’t explain.

In eighth grade, he tried out for football, but his grades suffered and Brown finally told him he had to quit. “I told him, ‘Grades before sports. If you ain’t got the grades, you ain’t gonna be able to play no sports.’ ” He wasn’t happy about that.

Without doubt, the turmoil in the family took its toll. When Brown and McSpadden broke up in 1999, Michael followed his mom to a new school district. Then he did a year’s stint at Jennings. Sometimes he would call his father, asking to be rescued. “And the two different families, we really didn’t get along, so it was kinda hard for me to go pick him up,” Brown says in a pained, quiet voice. “I had to have a family member go get him and bring him over to the house.”

The first time Cal met Michael, he was about sixteen, and they came home to find him sitting on the porch. “Mike-Mike had obviously had a little spat with his mother, and then she dropped him off over there,” Cal remembers. Brown was annoyed and fussing with him about being disrespectful and Michael never said a word. Finally he said, “Dad, are you finished?” Brown said he was. “Now would you like to hear my side of the story?”

Shortly after that, Michael came to stay with them. But he flat-out refused to go to school, sulking in his room for about three months. “It was a big struggle,” Brown says.

“He couldn’t focus,” Cal says. “He didn’t like it.”

Brown admits he was pretty worried. “Because he kind of had his mind made up.”

“He got bored,” Cal says.

“Just like me,” Brown says.

“He lost interest in stuff so quick.”

“Just like me,” Brown says.

That’s when Cal stepped in. She’s easygoing, a hugger, and Michael cleaved to her so eagerly that Brown got a little jealous. Michael told her things he didn’t tell anyone else—that he didn’t believe in God, which shocked her, and that his greatest fear was “not to be loved.” With college degrees of her own, she sang the praises of knowledge. “Education is everything. Especially as a black man. If you don’t have an education, you don’t have anything.” He never said much in response. She’d ask him, “What do you think?” He’d say, “Well, just give me a minute.”

Then Michael heard about a program where he could go to school part time and complete the credits fast. So he did that his senior year, signing a contract where he promised to keep up with the homework—and that was another struggle. When graduation came around, he turned up short on some phys-ed credits, but he buckled down for two more months—which is why he graduated at the beginning of August, just a week before he died.

They weren’t thrilled with his rap songs, which had lyrics that range from “Smoking on this dope till I choke” to “I need God and my family,” but Cal figured they were an outlet for venting. “Because I had told him at one time, you know, ‘You can’t just be angry about stuff. You have to vent.’ ” Brown wasn’t impressed. “I listened to some of it. I basically told him, ‘Just keep it as a hobby. Let’s stay focused.’ ”

But mostly they focused on the daily happiness. He played the tuba in sixth grade, played his video games, played catch in the street, football and kickball. “Just a normal kid, man.” At the thought, Brown flashes a sweet gold-toothed smile so sudden and brief it seems like a mirage.

When Cal became ill in January of 2013, Michael was her biggest supporter. If he wasn’t at the hospital by her side, he was on the phone with encouraging words. When she came home, he was always there in her face. “What are you doing?” “I’m going to the mailbox.” “No, you’re not. Sit back down.” She couldn’t even carry her own purse—she laughs at the image of that huge guy tenderly carrying her purse.

That summer came something that they regarded as a sign. “You want to tell him?” Cal asks. “Or you want me to tell him?

“You can tell him,” Brown says.

“He called and he said that he had just took a picture.”

“He called me,” Brown says.

“It had rained, and I guess he was looking at the sunset, a tree in the right bottom corner, and then in the middle it was the moon and some clouds around it. And on the other side, it kind of looked swirly. So he sent us the picture and he was like, ‘Look at it and tell me what you see.’ And I said, ‘I don’t see nothing.’ And then we started laughing.”

“And he got upset,” Brown says. “He was like, ‘I’m serious, Dad. I’m not playing!’ ”

“Then my sister looked at the picture and her boyfriend, my mom—we kind of passed the phone around the house and we were like, ‘We don’t see it. What is it that you see?’ And he said, ‘In the middle, there’s an angel. The devil is chasing the angel into the eyes of God.’ And I told him, ‘If it’s truly a sign from God, it was meant for you.’ ”

Brown nods. “Some people see it, some people don’t.”

A few weeks later, he finally got to graduate. He was excited. They were all there with him and went out afterward for a celebration lunch. He seemed different, Cal says, like he was really growing up. “I took his dad back to work, and me and him hung out the entire day. We were about to move into a new home and he said, ‘Am I still gonna be able to paint my room the color that I want?’ And I said, ‘Let’s go to Lowe’s and you can pick it out.’ ”

Three months later, that can of paint is still sitting in the back of her van.

“Strange Fruit,” someone mutters.

“What is that?”

“Black men.”

Brown sits silently. But the church atmosphere helps a lot, he says. “Being out in the open as of now, I don’t think it’s real good for me. I think I need to be in an enclosed environment. I need to keep my family safe.”

He arrives that Sunday morning at Lee’s church—the Flood Christian Church, a former auto-repair shop built of cinder block, with low unfinished rafters, rehabbed and opened just a year ago—with Cal and all seven of their children, the baby in his arms. They’re standing together, like they should be in one of those inspirational church posters with Jesus behind them and a rainbow overhead. Their teenage daughters are singers and soccer players. One even went to a soccer clinic at the White House. And it seems significant that he chose to join such a poor and intimate church—in his modesty, his humility, and his stubborn pride, he must have felt like it was the right place for him.

Lee launches into a sermon on Jephthah the Gileadite, who was denied by his father’s family because his mother was a prostitute. He gets into some earthy details, confessing his own sins and imagining the things poverty might have forced some of his parishioners to do. The point is Jephthah could have taken his rejection as an indication that his life was over and he would never amount to anything, but instead he became a mighty warrior. All of this is transparently aimed at Brown. “How many of you have lost more than you can imagine this year alone?” he asks.

Brown raises his hand.

“You must understand that in the breaking season, there has to be a restoration that immediately follows,” Lee says. “God would never break you without restoring you to a better place.”

They pray in a circle, holding hands.

Afterward, as they prepare to caravan over to a church that has a baptismal pool—the Flood is too poor to have its own—Brown talks about his plans for Christmas. He’s going to dress up as Santa Claus and give away gifts. Yesterday, he and Cal gave out ninety Thanksgiving turkeys door to door. They’re doing their best to “turn a negative into a positive,” he says.

As he speaks, Brown keeps one eye firmly on his toddler, breaking off to mind him. “Where’s your jacket? Put on your jacket.”

Half an hour later, Pastor Lee climbs into the baptismal pool. “Hit me with that old-school song,” he says, and unaccompanied voices sing, “Take me to the water, take me to the water, take me to the water to be baptized.” Cal goes first and comes out to applause. Then it’s Brown’s turn. He takes the hands of Lee and a deacon and steps gingerly into the tub, another rare smile on his face. “In obedience to the great head of the church,” Lee intones, “we baptize this young man upon the confession of his faith in Christ.” Then he takes one of Brown’s arms as a deacon holds the other and dunks him backward into the tub—“None but the righteous, none but the righteous”—hauling up him again to cheers and hallelujahs. Brown comes up grinning. Cal hands him a towel and hugs him.

For a moment, he says, he wasn’t thinking about anything.

When she finally saw it for herself, it ripped through her. “I’ve never seen him like that. I knew that he was angry, but I thought that we had kind of got, you know, through that.”

She remembers a fight he got into earlier in the year. The way he told the story, some guys on Canfield jumped him because his size made him a challenge. “He was so upset. He was like, ‘I didn’t even do anything, Cal.’ ”

For a few minutes, she diverts herself with happier stories, the way her kids jumped on him when he came in the door, his glee when she bought big glass plates to fit his jumbo-sized meals. Sometimes he’d call her just to hang out, or beg her to bring Chinese to school for lunch. “I think his past tore him apart,” she says. “You know, because for a long time he didn’t feel like he had a purpose.”

She told him he was going to be a great father because the kids loved him so much. And she would hug him and he would hold her so tight. “Nobody has ever hugged me as much as you,” he said once. She really thought he had turned the corner. On Sundays, when she and her mother would have a fellowship, he would usually sit there listening to his music. But lately, he started leaving one earphone off. Then he started taking his earphones off altogether. “He would be asking questions about the things we did as a family, how we fellowship. He would catch me reading my Bible and he would be like, ‘What are you reading?’ So then it just got to the point where, on Sunday mornings when he heard us, he would just automatically get up because he knew we were goin’ in the kitchen to play our music and laugh and talk and cook. It was like the music opened his eyes. You know, because I would see his foot patting, like ‘I’mma do it, but I’m not gonna let nobody know I’m doin’ it.’ ”

One day, they went for a picnic and they were lying on the blankets looking up at the sky. She said, “Dude, you say you don’t believe in God. Just look around! How do you think this happened?” He asked her, “So how did it begin?” She told him to read Genesis and Revelation and bought him a Bible, but he would read it only with her. “If he was at one of his grandmothers’ houses, he would call me. ‘You sleepin’?’ ‘No, I’m not sleeping.’ He’d say, ‘You wanna read together?’ ”

At this point Brown, who has been doing a local TV interview in another room, comes into the church. Cal asks what questions he got.

“Do I forgive Darren Wilson.”

“Babe, you were supposed to say yes.”

“I did.”

“Do you?”

“No.”

Cal laughs and Brown clarifies.

“His actions, what he chose. Might actually be a good guy, just had a bad day.”

Dig in! Ham hocks and green beans, turkey, ribs, mac and cheese, dressing, corn, and did you get any of the oxtail and beans? An uncle grows them himself, in his yard, they’re organic. And don’t worry about being so polite—grab that food while it’s still there.

Ready for dessert? Cal’s mother spoons some banana pudding into a plastic to-go cup, and man is it sweet. On the tablecloth, people have written thanks for God, for family, for being with good people, for Mike-Mike. Cal wrote “family and favor,” meaning God’s favor and all his small blessings. Brown hasn’t written anything.

Back in the man cave, the men talk about the game, absent relatives, the old homestead down in Mississippi, and those damn coyotes that keep going after the chickens. Brown laughs and leans back into the sofa, smoking another Newport as the men drift into an extended conversation of different stadiums and games they’ve seen—Edward Jones Dome has gotten so bad it’s worse than a teen club, one says, and Brown laughs loud at the slam. The sound is startling after all his shy smiles. He saw the Redskins in Washington and made the mistake of wearing his Rams hat. “Them fans are pissed off—they were upset. They were about to riot outside.”

No one bothers to mention how differently such a riot would be received. That knowledge is implicit, bred in their bones, a fact of American life, like crappy schools and dead-end jobs and highway stops and the old friends who died from gunfire. Then, without prompting, Brown gets closer than ever to facing that cigarillo video. “I don’t know about his actions. But I know his heart. I know my son.” As to what happened at the police car, if the cop grabbed him, Mike-Mike might have tried to pull his arm away. “He was a teenager,” he says.

In the morning, he has to fly to Miami for yet another event. Even if he were capable of pushing these things out of his mind, history and his own new sense of responsibility require him to do otherwise.

Cal comes down. “Do you realize we have to get up in a few hours?” she says. Brown just gives her a squeeze and turns back to the game. He can be tired tomorrow. He’ll put in his earbuds on the plane and when they get there, he’ll walk down the Jetway and try to be the person history has summoned. But please let this moment last a little bit longer.

He walks a guest to the door, accepts words of gratitude.

“Aww, you gonna tear up?” he says, smiling warmly. “Keep in touch,” he says. He stands out in the night air, taking in a moment away from his holiday gathering.

Tonight, everyone wrote on the tablecloth except for Brown. But what would he write? What can he possibly be thankful for at a time like this?

He thinks for a moment. Some answers in this world are easy—for Cal, obviously. His mother-in-law, who made her. And being able to get up every morning to fight for Mike-Mike.

The other answers are all in the future, in the ideal America that never quite comes, in the endless struggle that will deliver us—as it is delivering Brown—to grace.

John H. Richardson was born in Washington D.C. in 1954. Grew up in Athens, Manila, Saigon, Washington, Seoul, Honolulu, Los Angeles. University of Southern California ’77, Columbia University ’82. Worked at the Albuquerque Tribune, The Los Angeles Daily News, Premiere Magazine, New York Magazine, Esquire Magazine. Taught at the Columbia University, the University of New Mexico, and Purchase College. Currently Writer At Large at Esquire Magazine. Author of three books.

This piece was reprinted by EmpathyEducates with permission or license. We thank the Author, John H. Richardson for his kindness and heartfelt reflection. If only words could express how deeply we feel for the Brown family. “We who believe in freedom cannot not rest until it comes.” ~ By Bernice Johnson Reagon, Ella’s Song

Leave A Comment