Project Description

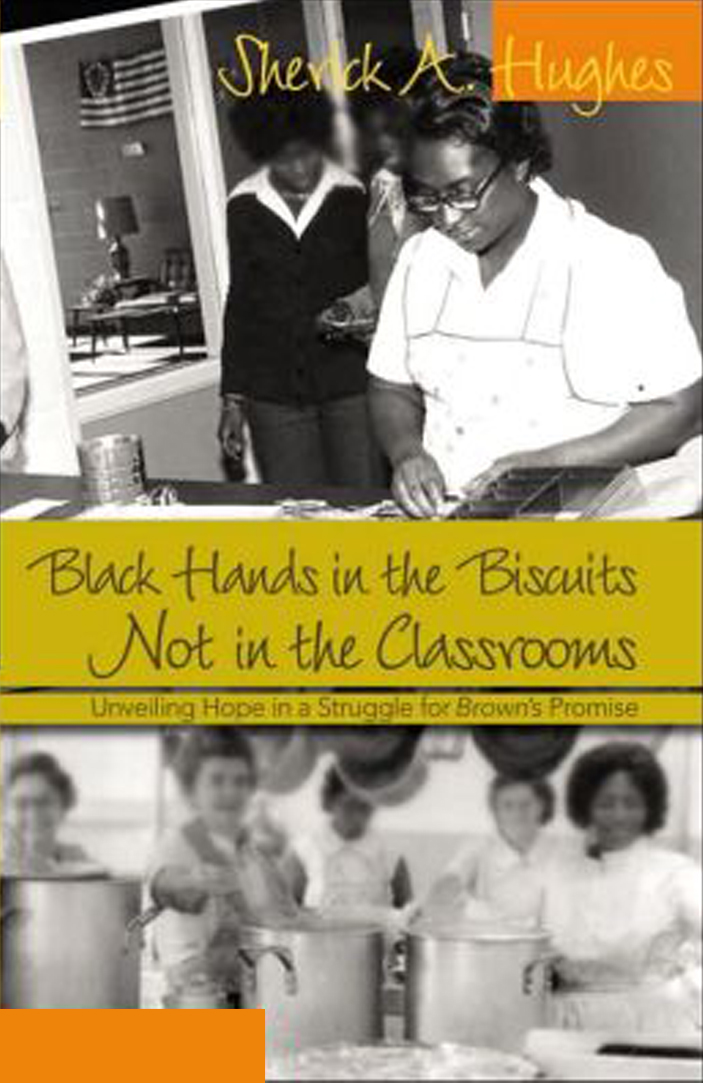

'Black Hands in the Biscuits Not in the Classrooms;'

Unveiling Hope in a Struggle for Brown’s Promise.

Two years ago, the 50th anniversary of Brown v. the Board of Education, the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 landmark decision to desegregate public schools, came and went rather quietly. During that anniversary year, a number of conferences, panels, and presentations referenced this monumental historical event, but overall, the remembrances were – dare I say it? – anticlimactic. Likely this is because, although Brown v. the Board of Education slowly ushered in revolutionary changes, today those changes seem hardly evident. As Gary Orfield, Director of the Civil Rights Project and Professor of Education and Social Policy at Harvard University, has repeatedly demonstrated in his academic and social policy research, we are far from realizing the full potential of Brown. In fact, during the past fifteen years, schools that in the 1960s and 1970s began the process of desegregation have slowly begun to resegregate along racial, ethnic, and social class lines (Orfield, 1996; Orfield & Lee, 2006).

As a result of weakened laws enforcing desegregation and the persistence of residential segregation along class and race lines, de facto school segregation has replaced the de jure school segregation of Plessy v. Ferguson, which in 1896 allowed for the emergence of the Jim Crow era and the idea that separate was acceptable if equal. However, as has been made evident in so much educational research, separate was not equal then and is not equal now.

These sobering facts bespeak the importance of seriously reexamining and reflecting upon the complicated effects of the early desegregation resulting from Brown – over the years, who have been the winners and who the losers? In stepping forward there are simultaneously and sometimes expectedly steps back. Even before social processes and policy decisions began to produce resegregation beginning in the late 1980’s, controversial and influential decisions were made in response to Brown that on some levels provided opportunity but in the long run may have worked against its promise. As we examine the successes and failures of educational institutions and policies that were wrought in the wake of Brown, we need to ensure that such evaluations consider the full implications of such change in all their messiness. In Black Hands in the Biscuits Not in the Classroom: Unveiling Hope in a Struggle for Brown’s Promise, Sherick A. Hughes does not retreat from this challenge but takes it head on.

Hughes focuses his historical ethnographic analysis on three generations of three African American families who have lived their lives in one small county in North Carolina, Northeastern Albemarle.

These families’ stories make up the crux of the text as Hughes reveals the varied ways Brown shaped their educational experiences and their responses to those changes. As is revealed in the subtitle, Hughes intends to stress that this is a story of “struggle” and “hope” in the aftermath of Brown. Weary of encountering flat portraits in the popular media and in some education literature that ahistorically portray African Americans in general as a social problem and of the black family as deficient, Hughes intends to reveal the power of the black family in providing hope and support in the face of adversity. He is striving to portray a “positive image” and a “clearer picture” (p. xviii) of the black family during the latter part of the 20th century and hopes to inspire his readers — many of whom he expects to be current or future educators or administrators — to action.

He chose this particular geographic location for his research because it was one with which he was familiar—he himself grew up in Northeastern Albemarle. It is for this reason that he refers to his methodology as a native historical ethnography, for in recounting and creating the historical educative experiences of his participants, he acknowledges his own role in these processes, realizing that his own experiences are of relevance in his final analysis. This overt inclusion of self is both a strength and weakness in the work. By acknowledging his history within this community and including first-person accounts and personal views, Hughes in many ways reinforces his credibility as an analyst—he knows his subject matter. This familiarity affords him a deep understanding of the area and its people, but as I will detail later it may occasionally blind him from integrating important information and providing further analysis for his readers.

Additionally, Hughes intimately knows the region’s history, both from having lived there and from having read books by authors who have likewise covered recent North Carolinian educational history. In fact, Hughes states explicitly that he considers this book to be part of a local trilogy, filling in gaps left by Vanessa Siddle Walker’s (1996) award-winning book Their Highest Potential and David Cecelski’s (1994) Along Freedom Road, both of which chronicled issues related to school life in North Carolina during the era of Brown. Hughes asserts, “It is not by design but by consequence that my school desegregation story seems to provide support and continuity to the accounts ‘spoken’ by Siddle Walker . . . and Cecelski” (p. 12). He says of this history, “I am not the first to tell some of it from the native history/native ethnography perspective. I am, however, the first to tell some of it that may not be familiar” (p. 12).

''I am not the first to tell some of it from the native history/native ethnography perspective. I am, however, the first to tell some of it that may not be familiar.'

~ Sherick A. Hughes

'My black hands are in his biscuits, and he’ll eat them, but he didn’t want his grandchildren to mix with the blacks.' (pp. 2-3)

~ Dora Erskin

In contrast to the struggles, however, these family members also remember the power that the Black community had drawn prior to Brown from having schools that they could call their own. Despite the fact that the schools serving Black students received fewer tangible resources from the larger community than the schools serving Whites — Black teachers and students remembered consistently using leftover or outdated texts and materials — Northeastern Albemarle’s Black citizens nonetheless had control over what occurred within the Black schools’ walls. Ross Winston, a retired school official, explains how segregated schools provided local Blacks with a place of their own: “Well it was sort of like a meeting place for blacks. I guess it was something that the blacks controlled, you what I mean, to a certain extent—their own PTA. It was just black-controlled, something that we controlled” (p. 33).

Within Black schools Black culture and history could be celebrated in a way that was not evident after the schools became more racially integrated. And perhaps most importantly, Black schools provided jobs for Black teachers and administrators.

With desegregation, the number of Black teachers and administrators steadily decreased as new teaching and administrative positions were regularly filled with Whites not Blacks. As is recounted by Willis Biggs, who came of age during the era of Brown and attended his first desegregated school in 1968, the loss of Black teachers affected not only the job market for local Blacks but also negatively shaped the dynamics of student/teacher relationships:

I think to me I was more comfortable with the teachers when they were all black, of course. The administration, you know, everything was all black, so you felt like they cared about you, instead of seeing this white lady here, just going on and looking at you as a number on a chair or whatever. But you felt more comfortable, and you saw these ladies other than school, too. You know, the teachers, you know, you would see them at church or at the store or something like that. . . . you would see them other places, but these white teachers you didn’t see them other than at school. (pp. 87-88)

When schools became integrated, this location of Black control within the larger community was lost, and many Black residents in Northeastern Albemarle found themselves to be merely participants and not leaders within an increasingly White-dominated educational system.

In addition to the educational history and the struggle that Hughes presents here, he also presents stories of hope and faith, and it is these stories that he places on the center stage. Participants remember pushing their children to be strong, have faith, and succeed against all odds, for they fundamentally believed in the promise of Brown and the power of an education.

As with the section reviewing local educational history, the strength of this section lies in the voices of Hughes’s participants. Their reflections reveal just how the struggle itself brought forth their faith and hope, providing a focus and means of making sense of the obstacles they faced. Candice, the youngest daughter of Dora and Nolen Erskin reveals the complicated relationship between struggle and hope in an account that she shares regarding the challenges of raising her three sons:

Sometimes we read together. Sometimes I hear, “I don’t have any!” and they know what’s coming next. “Get a book and read.” I think maybe if we were white I don’t think I would be preaching so hard. But in my head: “Black male, black male. The jails, the jails are full.” You know. These three, I’m trying to do my part to keep them out. (p. 113)

For Candice, an education will provide the way out and up, and so her emphasis on hope is bolstered. Hughes writes in his conclusion, “It is important that in these narratives hope is constructed in the process of struggle for civil rights inside and outside schools. It is equally crucial for interpreting the results of this study to understand story-telling as an artful teaching resource.” (143). Ultimately, Hughes intends to reveal how these stories themselves constitute a pedagogy that inform his participants’ educational perspectives, inform Hughes’s own perspectives, and should, finally, inform our, his readers’ understanding of these issues.

''It is important that in these narratives hope is constructed in the process of struggle for civil rights inside and outside schools.

~ Sherick A. Hughes

For example, in a poignant section Hughes describes Dora Erskine’s retelling of a story in which her daughter revealed to her that she had regularly carried a knife to school as a means of protecting herself in school. In sharing this story, Hughes reveals how utterly unresponsive the school was in dealing with racially motivated attacks on black students within the recently desegregated schools. However, Hughes himself comments very little on this issue. I wanted a more thorough analysis of the historical conditions and structural racism that served to create such fear in a little girl. The beginnings of such an analysis reside elsewhere in the pages of the book, but it is not here where it belongs reinforcing important points.

I can only assume that Hughes is expecting readers will get the point and make connections on their own. In other words, he assumes we know these people and their history as well as he does, and, in fact, many of us don’t. This is why earlier I stated that his strength — his in-depth, first-person knowledge of this particular community— may have, in unforeseen ways, undermined some of the potential effectiveness of his final analysis. I realize that what I am calling for may contradict part of Hughes’s intended purpose: the allowance of an organic understanding of history and of educative processes in a particular time and place, derived from the people themselves. Perhaps he desires the words of his participants to take precedence. However, as he himself readily acknowledges, the history he is presenting is one that is under construction and full of omissions.

People selectively remember what is most important to them. As a result, historical analysts are challenged with balancing the biases presented in historical documents and oral stories, with the hopes that their own selected story will present as accurate a picture as possible of at least one perspective. Readers can sometimes piece together the intended meaning, but because our knowledge of these individuals is limited and because most readers of this book will likely be outsiders — either racially, ethnically or regionally — I fear that the opportunity to communicate relevant, and potentially important, points will be missed.

Despite this complaint, Hughes’s book contains enough rich material to warrant readers’ attention, and he more than adequately convinces readers of his central thesis which is to highlight the interplay of struggle and hope in family pedagogy. In the larger scheme of educational research, his analysis provides a partial explanation as to why African Americans have consistently rated the value of an education more highly than Whites (Hochschild, 1995; Mickelson, 1990). Ultimately, Hughes presents readers with an understanding of how a pedagogy of hope might present itself in daily life and develop through the telling of stories like the story he shares with us. And, ultimately, he hopes that we too will learn from these stories, acting upon what we’ve learned thereby enriching the pedagogical power of his project.

References

- Hochschild, J. L. (1995). Facing up to the American dream: Race, class, and the soul of a nation. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

- Mickelson, R. A. (1990). The attitude-achievement paradox among black adolescents. Sociology of Education, 63, 44-61.

- Orfield, G. & Eaton, S. E. (1996). Dismantling desegregation: The quiet reversal of Brown v. Board of Education. N.Y.: The New Press.

- Orfield, G. & Lee, C. (2006). Racial Transformation and the Changing Nature of Segregation. Cambridge, MA: The Civil Rights Project at Harvard University.

About the Reviewer

Copyright is retained by the first or sole author, who grants right of first publication to the Education Review.

The Book and Review

$29.95 (paper cover) ISBN 0-8204-7431-2 | Reviewed by A. Fiona Pearson, Central Connecticut State University

August 8, 2006