New York State has received their just reward, the highest dishonor. The schools statewide are known to engage in “double segregation.” Students are increasingly isolated not only by race, but also by income. A Black or Latino student in New York State likely attends a school with twice as many low-income students as their white peers. This is quite the distinction and one that must mean a lot. To he declared the most segregated in the nation. That is quite the accomplishment.

Perhaps, Connecticut wants to keep up. They too want to achieve. How else might we explain what appears to be competition? Acceleration in segregation must be is the key that opens charter school doors and sadly closes others. It is our children who suffer. While the predicament or predilection is apparent in our public institutions, it can barely compare to what we see in countless charter schools. Changes in school enrollment policies have only worsened the problem. To better understand, let us look to a recent report, “Choice Watch: Diversity and Access in Connecticut’s School Choice Programs.”

Report Warns of “Hyper-Segregated” Charters | New Haven Independent

New Haven’s charter schools are too black and brown, a new report concluded—sparking a debate over who should get seats in coveted schools.

The report, issued Wednesday morning by the New Haven-based advocacy and research group Connecticut Voices For Children, raises difficult questions: Are charter schools hurting kids through racial isolation? Should they open up seats to wealthier white students, even if that means turning away poor minorities? Do black kids need white kids in the classroom to succeed?

The report, “Choice Watch: Diversity and Access in Connecticut’s School Choice Programs,” examined the demographics of Connecticut’s magnet, charter, traditional public district and technical schools.

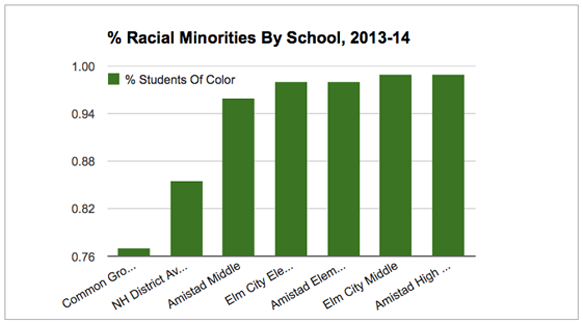

Click here to read the report. Among the report’s findings: The majority of charter schools in the state are “hyper-segregated,” with over 90 percent of students in a racial or ethnic minority.

That’s especially true in New Haven, where students at the five charter schools run by Achievement First are between 96 and 99 percent black and Hispanic.

That racial isolation is dangerous, argued report co-author Kenny Feder, because it denies black and white students the benefits of racial integration, including improved “achievement, long-term success, civic engagement,” and the opportunity to “engage in a multi-cultural world.”

The report raises “concerns” about charter schools’ “compliance with established goals of racial and ethnic integration and equal access for all students.”

Dacia Toll (pictured), CEO of Achievement First, said in a perfect world, “schools would represent the rich diversity that society has to offer.” But right now, black and brown kids don’t have many good options for school, she said. “We have three to five applications for every seat. Every seat that we give to a more affluent child who has more options is taking away a seat from a higher-needs family who doesn’t have as many options.”

“Do we care more about the color of the skin of the student that you’re sitting next to in class, or student achievement and long-term outcomes?” she asked.

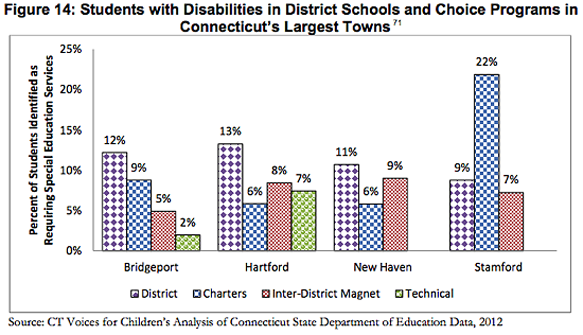

The report also found that charter and magnet schools are failing to serve as many English-language learners and special-needs students as traditional public schools do.

Racial Isolation

State law requires all charter and magnet schools to reduce racial and ethnic isolation of their students. But only magnet schools are achieving that goal, according to Ellen Shemitz, executive director of CT Voices for Children.

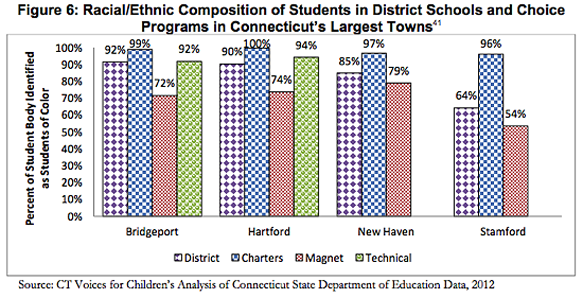

New Haven charter schools serve 97 percent minority students, compared to 79 percent in New Haven magnet schools and 85 percent in New Haven’s public school district as a whole, according to the report, which is taken from an enrollment count on Oct. 1, 2011. That reflects a larger statewide trend (illustrated in this graph).

Charter schools accept kids through a public lottery; they operate under their own charters under state funding and supervision. Magnet schools are schools of choice that operate within a public school district; they also accept kids via blind lottery.

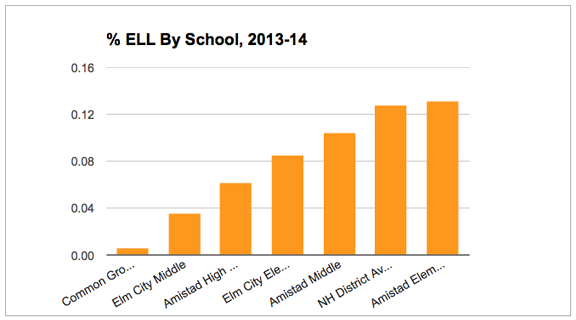

% Racial Minorities By School, 2013-14

New Haven’s five charter schools run by the Achievement First currently each have a high concentration of minority students, between 96 and 99 percent, according to current data provided by the charter network (depicted in this graph).

That means that instead of offering kids more equality and integration, the charter movement stands to “replicate or worsen segregation,” the report argues.

Common Ground High School, an independent charter school in West Rock, is an exception to that trend: The school is almost “integrated,” as that term is defined by the state (between 25 and 75 percent racial minorities). At Common Ground, 23 percent of students are white, according to Director Liz Cox. Cox recently offered that statistic in the Independent’s comments section because her school was coming under criticism from the opposite angle—that minority city kids are losing opportunities because so many Common Ground students are white.

Report co-author Robert Cotto, a member of Hartford’s school board, called on the state to hold charter schools accountable for the racial balance of their schools.

“With limited exceptions, Connecticut’s school choice programs successfully promote racial and ethnic integration only when they have clear, enforced, and measurable standards,” said Cotto.

Magnet schools are held to the kind of measurable standard that Cotto is talking about: They are supposed to have no more than 75 percent, and no fewer than 25 percent, white students. Charter schools have no comparable requirement, Cotto said. He suggested the state create a “measurable” standard to determine whether charter schools are successfully reducing racial isolation. Cotto suggested that if charter operators like Achievement First want to create a school that targets black and brown students, they should have to apply for a waiver from the state, and the bar for winning a waiver should be “very high.”

“Integration by race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status has academic and social benefits for children of all racial and ethnic groups,” the report argues. Benefits include “access to other successful peers, increased resources, a broad curriculum, and a diverse, skilled group of educators.” Segregated schools and neighborhoods “can have a negative impact on children and families’ long-term development, well-being, and access to services and opportunities,” the report argues. (Click here and here for related research backing up those points.)

Santia Bennet (pictured)t, a parent leader at Achievement First (AF) schools in New Haven, agreed with Cotto. She said she would support a 25 percent set-aside for white student inside AF schools.

“If you just know one race, you kind of put yourself into a box,” she said. Kids need to interact with people outside of their own experience, she said. “Having a mixture of races

AF CEO Toll, meanwhile, frowned on giving up coveted charter-school seats to wealthier white kids. She said AF schools meet a crucial need for students like Bennett’s and enable them to succeed in life. After eight years in AF schools, Bennett’s son is now about to graduate from Bates College, and is thriving among white students there. He “is now positioned to have all kinds of opportunities with a college degree,” Toll argued.

“What if we had given that seat to some other child because they were white? Simply because they were white?” Toll asked.

“This is not a theoretical issue,” she wrote in a follow-up email. “It has very real, personal and practical implications. “We have three to five applicants for every open seat, and a lottery determines who gets in. One hundred percent of our graduates are admitted to college. If we were to impose racial or economic quotas on the lottery, some number of low-income students would be denied a potentially life-changing opportunity. Would that really result in a better society?”

Toll said she respects CT Voices for Children, but “are they honestly more concerned about racial and economic isolation in the handful of schools that are actually serving low-income students well? Where is the outrage about the hundreds of schools that are not serving these students well? Do we care more about the color of the skin of the student that you’re sitting next to in class, or student achievement and long-term outcomes?”

Toll noted that even racially integrated schools have internal achievement gaps, whereas AF has succeeded in closing the achievement gap in some cases.

“Given our student demographics, we have worked hard to create other opportunities—notably summer opportunities that are racially and economically diverse,” she added. (Pictured: Amistad Academy’s lacrosse team, which plays suburban teams.)

In an email message, state education spokeswoman Kelly Donnelly declined to comment on whether the state should adopt a new, measurable integration standard for charter schools. She issued a more general statement that more defended schools of choice.

“The state is committed to making sure that all children have access to a quality education, regardless of their zip code. That’s why we’ve invested hundreds of millions of dollars to improve public schools,” she said. “Public schools of choice have created high-quality options for thousands of Connecticut families. These choices can and do take multiple forms. Such schools are part of the solution—and are just one part of our larger, comprehensive education reform efforts.”

English-Language Learners

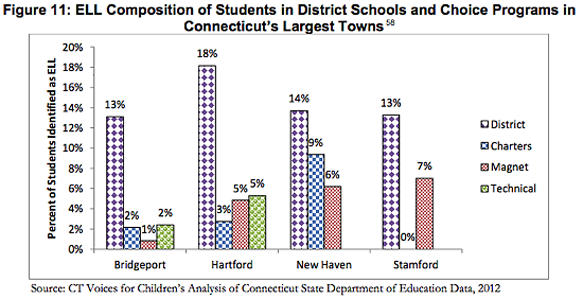

The report also concluded that magnet schools and charter schools are teaching disproportionately fewer English-language learners than are traditional public schools.

9 percent of New Haven charter school students were English-language learners (ELLs), compared to 14 percent in the district and 6 percent in magnet schools, as of 2011, according to the report.

On the whole, magnets fail to serve very many ELLs, Cotto said. He cited one exception in New Haven: John C. Daniels School, a dual immersion school where 19 percent of students are ELLs.

AF schools have boosted their numbers of English-language learners. The chart above shows numbers for the current year, as reported by the charter schools and the public school district.

The report defines an English-language learner (ELL) as a student whose dominant language at home is not English, and who fails an English proficiency test.

Toll said that’s a problematic definition: “The moment we help children to pass a reading test, they are no longer ELL.”

“We have experienced a lot of success with ELL students,” Toll said. After few ELLs enrolled in AF schools, she said, “we realized we had to be more intentional about getting the word out to them about their choices and options.” The 2013-14 kindergarten class at Amistad Academy Elementary is 29 percent ELL—a sign that AF is doing well at recruitment. If the number of ELLs shrinks in the upper grades, that may be because they are passing out of reading tests and beginning to master English, Toll noted.

The report also chides charters and magnet schools as a whole for failing to serve as many students with disabilities.

Six percent of New Haven charter school students were classified as needing special education, compared to 11 percent in the district and 9 percent in magnet schools, according to the 2011 figures included in the report.

% ELL By School, 2013-14

Common Ground High .006 • Elm City Middle 0.036000000000000004 • Amistad High School .062 • Elm City Elementary .085 • Amistad Middle School .104 • NH District Average .128 • Amistad Elementary .131

Current stats show AF schools still fall below the district’s special-ed average as of the current school year.

Toll said AF cited two reasons AF numbers are lower than the public school district: It’s difficult to target recruitment to special-needs kids. And if a school is successful with a kid, that student will be declassified from the special education label.

“The more effective you are at helping students, the lower your numbers,” she said.

Pastor Eldren Morrison (pictured), who just won approval to start his own charter school in New Haven, said he has discussed with New Haven schools Superintendent Garth Harries how to ensure the school serves its due share of students with disabilities. Morrison has said his vision is to open a school that would reverse the fortune for kids in the African-American neighborhoods of Newhallville and Dixwell, where his church sits. He has said he aims to intervene before they get caught up in gun violence or end up behind bars.

Morrison said he sees the value in a racially integrated school, but he does not support a specific state mandate to set aside 25 percent of the seats for white kids.

“My first push is for the kids in this community, to give parents the option, that choice,” he said.

He said he is putting greater focus on the curriculum than the racial composition of the student body.

“I think our kids will learn no matter who’s in the classroom with them,” Morrison said.

Leave A Comment