Photo Credit: Getty Images

For two score and ten years we have misremembered and made mythical the stories we prefer to believe. Perhaps that is why, fifty years later, there is a need to March again for Jobs and Freedom. In 1963 Bayard Rustin, Martin Luther King’s closest advisor, organized what is now legendary, distorted as the “memory of “The Dream” is. At the time, his efforts and those of 250,000 African-Americans Marchers were misunderstood or equally as troublesome, hidden. All those years ago, countless newspapers did not cover the event. If they did much of the reporting was relegated to back pages. Today, the esteemed Washington Post expressed its regrets for “An overlooked dream, now remembered”, but what will tomorrow bring. Will we, as Americans only feature what we want to be the focus, or will we share and recall what was real? Let is look back on history and learn. Let the commemorations held in homage this week be more than an acknowledgement of the Unfinished March!

Ten Things to Know about the March on Washington

Submitted by John Adams

Originally Published at Teaching Tolerance on August 28, 2012

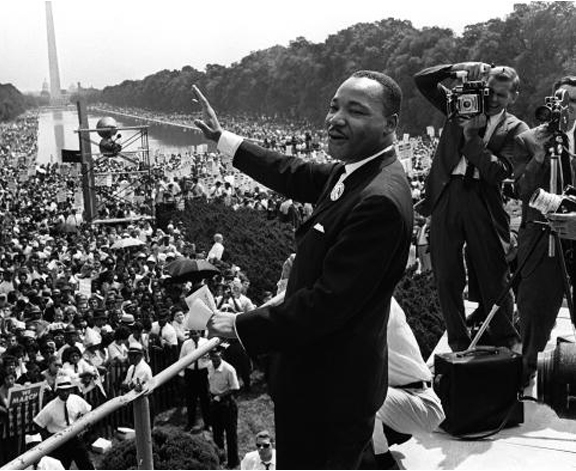

The 1963 March on Washington is perhaps the most iconic event from the modern civil rights movement. Now a full half-century ago, a quarter of a million Americans gathered to show solidarity with African Americans. While images of the March on Washington are engrained in our collective conscience, few realize that the event defined and crystallized a social, political and moral revolution. To commemorate the event, here are 10 things you may not know about the March on Washington.

1. The official name of the march was “The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.” The goal was to rally support for President John F. Kennedy’s civil rights bill and call attention to the economic challenges confronting the African-American community.

2. A March on Washington Movement was first organized in 1941 by A. Phillip Randolph to address employment discrimination toward African Americans. Although an actual march did not materialize, Randolph’s threat to protest on the National Mall during World War II forced President Franklin D. Roosevelt to issue Executive Order #8802, which prevented discrimination in the national defense industries.

3. The March on Washington in 1963 was organized by Bayard Rustin, Martin Luther King’s closest advisor, and a gay black man.

4. W.E.B. Du Bois, co-founder of the NAACP, died on the morning of the march, in Accra, Ghana, at the age of 95.

5. The March on Washington was held exactly eight years after the 1955 lynching of Emmitt Till.

6. Although women had been active organizers in the civil rights movement since its inception, no women were selected to give any of the day’s keynote addresses. As the only woman on the March’s planning committee, Anna Arnold Hegdemen protested the exclusion of female freedom fighters. Josephine Baker addressed the main crowd before the official program began, and Myrlie Evers was scheduled to conduct a “Tribute to Women.” When Evers got stuck in traffic due to a scheduling conflict, Daisy Bates substituted, making her the only woman to address the crowd during the official program. Bates spoke 142 words.

7. Two separate parades were held for male and female civil rights leaders. The men marched down Pennsylvania Avenue. The women, who included Daisy Bates, Josephine Baker, an entertainer-turned-activist, and Rosa Parks, marched down Independence Avenue.

8. The most stirring parts of King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, delivered on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial during the march, were improvised. King was inspired by gospel legend Mahalia Jackson who shouted out from the crowd, “Tell ‘em about the dream, Martin!”

9. King’s speech didn’t immediately garner the attention it now receives. Following the march, the Washington Post didn’t mention “I Have a Dream” at all. Randolph’s speech was featured instead.

10. King and the other senior civil rights leaders censored the speech of John Lewis, representing the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. They felt he took too hard a line against the Kennedy Administration. Here are some of his omitted words: “In good conscience, we cannot support the administration’s civil-rights bill, for it is too little, and too late. There’s not one thing in the bill that will protect our people from police brutality.”

John Adams, PhD candidate, History Department, Rutgers University