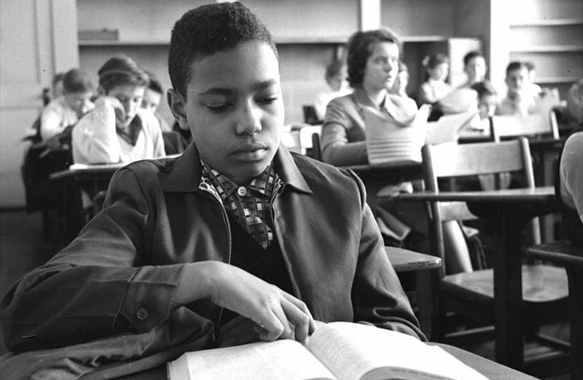

By Tracey M. Lewis-Giggetts | Originally Published at Vitae Chronicle. May 6, 2015 | Photographic Credit; In the classroom: James “Skip” Turner Jr. sits in class at Norview Junior High School. (Virginian-Pilot file photo)

On the first day of a new semester, I often have students introduce themselves via a simple icebreaker. I ask them to state their name, major, and an adjective that best describes their personality and begins with the first letter of their first name. Inevitably, I’ll get the Joyful Jens, the Bold Brendas, and the Sarcastic Sams.

Last fall, “Roger,” an African-American student studying business, gave this response: “I can’t think of anything really. I would call myself ‘Reading Roger,’ only I’m no good at reading. You’ll see. I suck at it.” (I’ve changed his name to protect his privacy but it did begin with an “R.”) In an effort to boost his confidence, I said, “Well, I’m just going to call you ‘Reading Roger.’” His answer? “Pshh! Whatever. Like I said, I suck at reading. Watch. I’m horrible.”

Needless to say, I was taken aback by how certain he was about his alleged incompetence. I firmly believe that the way students think of themselves (and how they articulate those thoughts) is directly connected to their ability to learn. In Roger’s case, the lies about his capabilities were already firmly embedded and he’d bought every single one.

I wish I could say that this was an isolated incident. But it isn’t. Every year, I encounter countless black male students — particularly at the community-college level — who demonstrate a lack of confidence about their ability to master a subject or, in the case of the kinds of courses I teach, their ability to communicate or write well. They don’t all boldly declare it on the first day. Some just refuse to speak or read aloud. Others give disclaimers in their writing: “I’m not sure if this is what the author meant but …”

Those are some of the breadcrumbs that lead me to conclude that these students may not have had anyone ever tell them that their thoughts mattered, or that they were capable of doing well. If the measure of confidence in the classroom is a student who exhibits engagement with the learning process or, at the very least, believes that he can accomplish the course’s tasks, then sadly, too many of my African-American male students fall short.

This phenomenon is often called the “Confidence Gap” and is, I believe, evidence of the ongoing diminishing of black males’ humanity. It’s not evidence of an inherent deficiency, as some would like us to believe. The intellect is an integral part of a person’s ability to reason and make decisions, and when it’s not cultivated, there are consequences.

The confidence gap, as I’ve observed it, is directly linked to the core theme of recent civil rights protests against injustice and police brutality. In short, when black lives don’t matter outside the classroom, that directly affects how black men perceive themselves inside it. The same stereotyping and racial profiling that leads some unarmed black men to be killed in the streets is also killing their minds and, consequently, their potential to excel in an academic environment. You can’t bombard a person from the age of five on with images that suggest that they are intellectually inferior and expect that it won’t affect how they see themselves and perform in the classroom.

The typical response to that observation — and one I hear recounted ad nauseam in higher ed thinkpieces and professional development workshops — is that that these young men just don’t want to learn. As if there is some “desire to learn” gene that some black boys are not born with. Liberal pundits may blame the academic difficulties of young black males on the lack of parental involvement or influence.

OK, I’ll concede there are other factors — family engagement being a significant one. And seeing the adults in their lives — their daddies, uncles, godfathers, and friends — treated poorly by police day in and day out doesn’t help of course.

Yet I submit that the most acute influences on this front come from outside the family dynamic and, in some cases, from outside the neighborhood. Even in 2015, most media images of successful black men are of actors, singers, rappers, reality-show stars, and athletes. By contrast, black men who are doctors, lawyers, and public intellectuals don’t appear anywhere near as often in the media or on television and movies. For many black young men, President Obama was the first non-athlete/rapper/actor they’d ever seen have any substantial influence or prominence. Of course, these same young men have also watched the president denigrated at every turn — and not always for his policies which is to be expected. The president has had to walk a tightrope when it comes to race — everything from having to give an hour-long speech on the subject during his campaign because of the controversial comments of his former pastor, Rev. Jeremiah Wright, to dealing with racist name-calling against himself, the first lady, and his children.

So most of the images of black men are of entertainers and those that aren’t are ripped apart regularly in the media? Not the most encouraging prospects for these young men.

Too many black boys spend their K-12 years in classrooms with teachers who, often inaccurately, label them as academically deficient and/or as behavioral problems on the first day and segregate them from the rest of the class under the guise of differentiation. These teachers, sometimes unconsciously, perceive academic excellence in black males as the exception and not the rule.

When I interviewed “Thomas,” a 43-year-old black male for this article, he vividly recalled his school-age experiences:

“I remember being in third grade and being given an assignment to write a story. I was so excited. I’d been struggling with my homework but really wanted to do well this time, you know. So I went home and spent all Saturday at the kitchen table writing my story. Copying it over and over again. Reading it back to myself over and over again, making sure it said exactly what I wanted it to say. I was really happy with what I wrote when I turned it in to my teacher. A couple of days went by and she returned the papers but didn’t give mine back immediately. ‘Did someone help you write this paper?’ she said. I was like, ‘No!’ She kept asking me. Accusing me, really. I was so confused. I was a kid — 8 years old. I wasn’t thinking about racism. I later realized, after hearing about her treatment of other black children, that this woman actually believed I wasn’t capable of doing the work. So that experience stuck with me.”

When a black boy’s ability is denied time and time again, there’s inevitably an impact on what he believes he can accomplish as a man. Fortunately, some, like Thomas, use this treatment as a motivator for success. “Over two decades later, when I finished my bachelor’s degree, I thought about that teacher,” he told me.

A few of my black male students have lived long enough to know the deal and not care anymore. They have the most profound ideas and express them in unique ways. I watch them blossom under my encouragement and rise to the challenges I give them. Their light shines brightly as I try to push them out of the gap and onto the level ground with their fellow students.

Others, like Reading Roger, are less fortunate. He did not do well in my class.

I get it. It’s easier to buy the lie and see yourself as others see you. It’s hard not to succumb to low expectations when you realize you will have to fight tooth and nail to prove your worth — and yet may still end up dead: emotionally, spiritually, and, as we’ve seen so often of late, physically.

I desperately wanted Roger to see himself as Reading Roger. I wanted him to see his own mind as beautiful, even if he has to work a little harder or differently than other people. I wanted him to not give up on himself. But I also knew that fixing 20 years of damage to his self-esteem in 15 weeks was nearly impossible.

Unfortunately, there are many more like him — Reading Randys and Brilliant Bobbys who are convinced, long before they reach my freshman comp class, that they don’t have what it takes to succeed in college. Their frustration with my course is fueled by that mistaken belief and often leads to behaviors that reinforce it. It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy: Some ignorant person believed that they couldn’t do the work so, therefore, they weren’t taught how to do the work. Because they weren’t taught how to do the work, they came to believe that they couldn’t do it, and so they don’t. When they fail, that just confirms what they were led to believe. And the cycle continues.

If young black men feel marginalized and out of place in my extremely diverse, multicultural, and, for the most part, supportive community-college setting, how many more feel that way walking into four-year, predominantly white institutions where people who look like them are even fewer and farther between?

What they need are more professors — lots more — who actually believe that the thoughts and opinions of black males matter, so they can learn to trust themselves and express those views.

I don’t want to imply that black men should somehow not be held accountable for their own actions. I don’t give passes in my class to anyone who does not do the work. But I also try, in a number of ways, to “stop the bleeding” when it comes to my black male students. I affirm them in the classroom by encouraging them — sometimes even requiring them — to speak up. I try to validate their experiences by placing them in any of the larger contexts in which we might be discussing. Recent events (Mike Brown/Ferguson, Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner) have allowed me to do that really well. We’ve read articles from various publications and from various perspectives on the subjects of systemic racism and police brutality. In class discussions and written work, all of my students — but my black male students specifically — had had to think critically about their place in these events. That helps students to see how their thoughts, ideas, and very being “fit” and are, therefore, valuable. And as with all of my students, I challenge black men in my class to own both their capabilities and shortcomings so that they know where they are, and, most important, can see a clear path to where they want to be.

The struggle to be confident in the classroom — to truly believe that you are capable of the kind of higher-level thinking and academic proficiency required — is certainly not exclusive to black men. But it’s infinitely more challenging for them to believe in their abilities when, in some cases, the only story they’ve ever been told about themselves has always had a bad ending. Changing the narrative must seem like an unfairly mountainous task since it’s one that many of their peers will never have to endure.

Tracey M. Lewis-Giggetts is a Writer, Editor, and Adjunct Professor of English, writing, and publishing at several colleges and universities in the metro Philadelphia area.

This piece was reprinted by EmpathyEducates with permission or license. We thank the Author, Professor Tracey M. Lewis-Giggetts and Vitae for their kindness and enduring scholarship. May we all learn life’s lessons…Through our actions and beliefs we teach the children.

Leave A Comment