By Andrea Gabor Originally Published at Newsweek. September 20, 2013

Long before Sci Academy, a charter school in New Orleans, had graduated its first senior class, the school was being heaped with accolades.

In September 2010, when Sci Academy was just two years old, its 200 excited students—then all freshmen and sophomores—filed into Greater St. Stephen Baptist church, next door to the school. Together with local dignitaries, journalists, and a brass band, the students watched on jumbo screens as the leaders of six charter schools from around the country appeared on The Oprah Winfrey Show. At the end of the show, they watched as Oprah handed each charter-school leader—including Ben Marcovitz, Sci Academy’s founder—a $1 million check.

Sci Academy is a flagship charter school and a model of the new data-driven, business-infused approach to education that has reached its apotheosis in New Orleans. After Hurricane Katrina in 2005, education reformers swept away what remained of the traditional public schools in what had been one of the nation’s lowest-performing districts. In their place, charters promised choice and increased accountability. More than 75 percent of New Orleans kids landed in schools controlled by the so-called Recovery School District, which was heavily dominated by charter schools.

“This transformation of the New Orleans educational system may turn out to be the most significant national development in education since desegregation,” wrote Neerav Kingsland, the CEO of New Schools for New Orleans, the city’s leading venture-philanthropy group incubating local charter schools, a year ago. “New Orleans students have access to educational opportunities that are far superior to any in recent memory.”

But eight years after Hurricane Katrina, there is evidence that the picture is far more complicated. Seventy-nine percent of RSD charters are still rated D or F by the Louisiana Department of Education. (To be sure, some charter operators argue that the grading system in Louisiana, which keeps moving the bar upward, doesn’t sufficiently capture the improvements schools have achieved.) Sci is one of two RSD high schools to earn a B; there are no A-rated open-admission schools. In a school system with about 42,000 mostly poor African-American kids, every year thousands are out of school at any given time—because they are on suspension, have dropped out, or are incarcerated. Even at successful schools, such as the highly regarded Sci Academy, large numbers of students never make it to graduation, and others are unlikely to make it through college.

Figuring out what has taken place in the New Orleans schools is not just a matter of interest to local residents. From cities like New York to towns like Muskegon Heights, Michigan, market-style reforms have been widely touted as the answer to America’s educational woes. (A recent editorial in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch called for local education reformers to “adopt the Louisiana model.”) New Orleans tells us a lot about what these reforms look like in practice. And the current reality of the city’s schools should be enough to give pause to even the most passionate charter supporters.

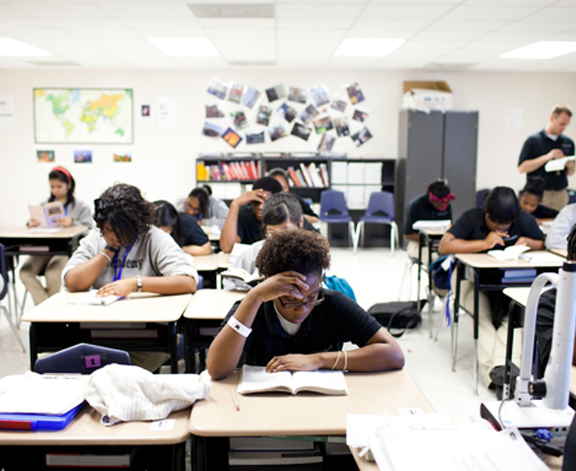

Everything at Sci Academy is carefully choreographed to maintain discipline and a laserlike focus on the school’s principal mission, which is to get every student into college. Each morning, at 8 a.m., the teachers, almost all white and in their 20s, gather for a rousing thigh-slapping, hand-clapping, rap-chanting staff revival meeting, the beginning of what will be, for most, a 14- to 16-hour workday. Students arrive a half hour later, and if asked “Why are you here?” and “What will it take?” are expected to respond “To learn,” followed by a recitation of the school’s six core values: “achievement, respect, responsibility, perseverance, teamwork, and enthusiasm.”

Both curriculum and behavior are meticulously scripted. As kids file into class, a teacher hands them their “entry ticket,” a survey that helps determine how much students retained from the previous class. An “exit ticket” distributed at the end of each class establishes how much kids have absorbed. Information from the exit tickets, as well as attendance, demerits for bad behavior, and “Sci bucks” for good behavior, are keyed into the Sci software system by teachers every night to help monitor both student and teacher performance.

After the storm, the state fired the city’s unionized teachers, who were mostly middle-aged African-Americans, an action that has been challenged in court. While a few schools have hired back teachers who worked in the pre-Katrina schools, the city now relies heavily on inexperienced educators—mostly young, white, and from out of town—who are willing, at least in the short run, to put in grueling hours. But at many schools, including Sci Academy, plenty of teachers last for less than two years. In New Orleans, teachers with certifications from Teach for America number close to 400, five times the level a few years ago.

Within the RSD, in 2011, 42 percent of teachers had less than three years of experience; 22 percent have spent just one year or less in the classroom, according to “The State of Public Education in New Orleans,” a 2012 report by the pro-charter Cowen Institute at Tulane University.

In part to help with this lack of experience, charter schools train teachers in highly regimented routines that help them keep control of their classrooms. The city’s charter-school advocates argue that in the aftermath of the storm, when charter operators had to scale up quickly, they needed to start with basics: first order and security, then skill building. “Kids expect high school to be dangerous. They come to school with their backs up,” explains Sci Academy’s Marcovitz, a graduate of the elite Maret school in Washington, D.C., and Yale University. He says the routines—which are borrowed from methods pioneered by KIPP, a national charter chain that also operates schools in New Orleans—are intended to keep students focused and feeling safe.

Maile Lani Photography/FirstLine Schools

The city now relies heavily on inexperienced educators—mostly young, white, and from out of town—who are willing, at least in the short run, to put in grueling hours.

In one English class last fall, a teacher who had been at Sci for about a year held forth on the fine points of grammar, including the subtle difference between modal and auxiliary verbs. As a few heads drifted downward, she employed a popular charter-school management routine to hold the class’s attention. “SPARK check!” she called. The acronym stands for sit straight; pencil to paper (or place hands folded in front); ask and answer questions; respect; and keep tracking the speaker.

“Heads up, sit straight—15 seconds to go,” she said, trying to get her students’ attention.

“All scholars please raise your homework in THREE, TWO, ONE. We need to set a goal around homework completion. I only see about one third complete homework.”

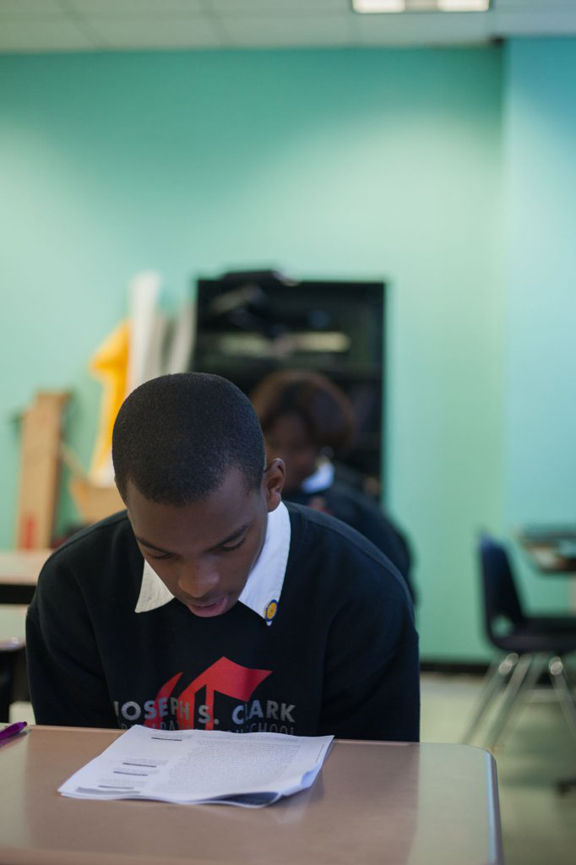

It’s a long way from the city’s charter-school roots. In the 1990s, the city’s first charter school, New Orleans Charter Middle School, was built on a progressive curriculum that used experiential projects and electives, such as bicycle repair and African dance, to foster a love of learning. The school became the most highly rated nonselective school in the city before it was devastated during Hurricane Katrina. But while its founders went on to create FirstLine, now one of the leading charter operators in New Orleans, the progressive roots of the charter movement have been swamped by the new realities of a competitive charter marketplace.

Now, driven by both government policy and philanthropic funding—which rewards schools for preparing students for college and penalizes those that don’t—most charter high schools in New Orleans describe themselves as “college prep.” This may seem an admirable goal. But in a school system where the number of eighth graders who passed the end-of-course tests required to get into high school has, according to the Cowen Institute, virtually stagnated at about 60 percent, the push toward college leaves behind many of the most disadvantaged kids, who already face enormous hurdles because of poverty, parental abandonment, and one of the highest rates of gun violence in the nation. For some of these students, college is not necessarily a realistic goal.

Of course, New Orleans had been a troubled school district long before Katrina. While schools were improving before the storm, charter advocates point to a faster rate of improvement in the years since. Yet pre- and post-Katrina comparisons are difficult, in large part because of a surge in funding for charters post-Katrina. (Andre Perry, an expert on education who ran a charter-school network in New Orleans, and Michael Schwam-Baird, an education researcher, estimate that per-pupil funding in the 2006–07 and 2007–08 school years was about double what it had been in the two years immediately preceding the hurricane and 50 to 100 percent greater than it was for the rest of Louisiana during the same period.)

One undeniable reality is that negotiating the new charter-dominated system has been complicated for students; it also has favored those who have the most parental support. The luckiest are students like Eddie Barnes, a star at Sci Academy, whose mother was able to navigate the highly confusing application process that, especially in the early years of the RSD, stumped many parents. (Part of what makes the New Orleans school system so complicated is that it is essentially two systems: the smaller, high-performing, mostly selective schools, which were never taken over by the state—though many were converted to charters—and the 60 or so schools within the RSD.)

Like most of his classmates, Eddie came to Sci Academy after a traumatic post-Katrina odyssey that began when he was 11 and fled the city with his parents and younger brothers, first for Texas and, eventually, Georgia. When Eddie’s mother, Anya Barnes, decided to return to New Orleans in 2008, her husband, the father of her two youngest sons, didn’t join her. So, the family returned to New Orleans fatherless, arriving three months after the start of Eddie’s freshman year. That was during the chaotic first years of the RSD, when parents had to apply to every charter school individually, which led to widespread allegations that schools cherry-picked their students. (Last year the RSD instituted a streamlined application process.)

Eddie and his mother made the rounds of the few RSD schools that still had openings and eventually found their way to Sci Academy, which had just enrolled its first class. (The two other schools Eddie tried have since been closed or taken over.) Anya Barnes, who had started college but never finished, was “inspired by Sci” and its college-prep mission. Eddie, in turn, was inspired by his mother and, three years later, wrote his college essay about the role she had played in his academic achievements.

In school, Eddie was a class leader. At 160 pounds and 5 feet 8 inches, he became captain of the fledgling basketball and football teams. He won Mr. Sci Academy, an award given to the student who exemplifies the cooperative values of the school. He was voted prom king. And he excelled academically: in his junior year, Eddie’s standardized test scores met the testing requirements for a scholarship to a Louisiana state school, as well as for a college trip to the East Coast that Sci’s college-placement officer was organizing.

By the time Eddie and his classmates were ready to graduate in the spring of 2012, the class seemed to offer vindication not only for the school’s no-excuses college-prep approach, but for the entire New Orleans charter model. Almost all the graduating seniors at Sci Academy—close to 95 percent—had been accepted at college. Eddie and a half dozen of his classmates would be returning to the East Coast, where they had won scholarships to attend schools like Middlebury, Wesleyan, Amherst, and Bard.

Yet, the results were not necessarily all they seemed—for either the Sci Academy kids who won college acceptances or the kids who never made it to graduation.

Like Marcovitz, Levey had attended a D.C.-area private school and an elite college—Sidwell Friends and Wesleyan, in Levey’s case. Marcovitz, says Levey, “wants this to be like a group of people who believe.”

Levey, boyish and intense, bought into the Sci Academy approach. At morning meetings, he could always be seen leading fellow faculty members in the motivational chants and rallying students. But the task was daunting from the start. “I’ll never forget the first time they showed me the spreadsheet of the kids’ GPAs and ACT scores going into senior year,” says Levey. “I was like, there’s no way.” The average ACT score was 17, well below the cutoff for a state scholarship, which was 20, in 2012, out of a possible 36. Levey says he was certain he had taken on an impossible task.

But Levey and Marcovitz were determined. Levey organized college trips, mentored the seniors, and worked the phones to his former college-admissions colleagues. Meanwhile, Sci Academy pulled out the stops when it came to standardized tests. In the spring, classes were regularly suspended for added studying. Seniors who scored below 20 on their ACT spent three weeks being tutored by Alex Gershanik, the local “test-prep guru,” at a cost, to Sci Academy, of $1,000 per student.

By the time Sci Academy’s first senior class was about to graduate, Levey’s doubts were deepening—about both the school’s college-for-all mission and the toll his work was having on his personal life. By the following spring, less than two years after joining Sci Academy, Levey decided to resign. “I believe every member of

Indeed, behind Sci Academy’s impressive college-acceptance rate were some troubling numbers. The school’s first graduating class was 37 percent smaller than the same class had been in the ninth grade—even though some students came to the school after freshman year and filled seats left vacant by departing students. The attrition rate has improved; the class of 2013 was 28 percent smaller than it had been in the ninth grade. But Sci Academy’s out-of-school suspension rate has been rising, reaching 49 percent in 2012, the second highest in the city and one reason kids transferred to other schools. Sci Academy says that its efforts to reduce suspensions by loosening some rules led to increased violence, including weapons on campus, which, in turn, led to a spike in suspensions.

Even kids who make it through high school and into college face hurdles. While the majority of Sci Academy’s graduates enrolled in four-year colleges in the fall of 2012, over 10 percent had either dropped out or transferred to junior colleges within six months of matriculating. (Marcovitz acknowledges that the school needs to both improve student attrition and help its graduates stay in college. Sci Academy recently appointed “college captains,” who will keep in touch with classmates and alert the school to any problems kids are having in college.)

Another fact that troubled Levey was student debt: the average Sci Academy student, if he or she completes college, will graduate with $22,000 to $27,000 in debt, according to Levey, even if the student is eligible for state or federal aid. Meanwhile, students who drop out will leave with thousands of dollars in loans. Says Levey: “A kid who is barely passing, but qualifies for a four-year college, who really doesn’t have any academic interests—why am I having them mark general studies on their college application, why? Or nursing or chemical engineering?”

Maile Lani Photography/FirstLine Schools

The progressive roots of the charter movement have been swamped by the new realities of a competitive charter marketplace.

Take the case of a student named Trevon, who, before enrolling at Sci Academy in his senior year, attended two other New Orleans charter high schools. The first declined to reenroll him in his sophomore year. The second was, by most accounts, a chaotic failure and closed after his junior year. Trevon fell behind a grade level and didn’t learn to write a research paper until late in his senior year. As recently as last spring, Trevon wasn’t sure college was for him; he was thinking of enlisting in the Army instead.

Encouraged by Sci Academy’s college-prep culture and after months of test prep, including a stint with the test-prep guru, Trevon eked out an 18 on his ACT—not enough for a state scholarship. But with a student loan, Trevon finally decided to enroll at Southern University at New Orleans for this fall. Even though the college has one of the nation’s lowest graduation rates—8 percent in 2009—Levey steered him and several classmates to SUNO because it is “cheap,” as Levey says; with work-study and living at home, he would have to take out no more than $1,000 or so per year in loans.

A Sci Academy administrator helped him register and pick a major—entrepreneurship—but two weeks into the fall semester, Trevon, unsure how to navigate a problem with his student loans, had neither purchased his books nor accessed Blackboard, the online portal where professors post class materials.

THERE IS no plan B in the college-for-all charter universe, in part because both the state’s accountability systems and philanthropists’ expectations are based on how successful the schools are in qualifying kids for college.

Louisiana’s school grading system rewards those whose students graduate in four years and score well on college-entry tests such as the ACT and advanced-placement tests. It penalizes schools—by giving them lower grades—if students take longer to graduate or perform poorly on the college-placement tests. Schools typically are reviewed every five years, but can be closed down after three if they do not meet the charter’s goals. In the 2010–11 school year alone, 10 New Orleans schools were closed or taken over, according to Research on Reforms, a local research and advocacy organization. The process left hundreds of kids in ninth to 12th grades scrambling to find space at a new school.

But for these experiments to work, the incentives will have to change. Under the current accountability criteria, alternative schools will always score an F and will eventually be closed, argues Elizabeth Ostberg, former head of human resources at FirstLine and founder of the NET, a new alternative school that got an F on its first 2012–13 report card.

“Why would you do this if you care about your school’s accountability score?” asks Jay Altman, the CEO of FirstLine, who gave the NET space at one of his schools during its first year of operation and is now piloting a vocational program as part of a takeover of Joseph S. Clark, a historic but failing high school.

Moreover, it is widely believed that private donors want to see as many students as possible go to college—an understandable inclination, but one that isn’t helpful for all kids. (Private donors can equal one third of a charter school’s budget: for Sci Academy, in 2011, $1.3 million of its $3.9 million budget came from private donations.) Ostberg, for instance, is convinced that her school was initially denied funding by a major foundation because the school’s mission did not emphasize college prep. It finally got the money, she says, in part by convincing the foundation that if New Orleans is to have a “successful education system,” it has to “address” the kids who aren’t going to college. “If we build great alternative schools, our college-prep schools will be better,” she says.

Many students are still falling through the cracks. In 2010, the year Ostberg received her charter for the NET, an estimated 4,000 teens, about 10 percent of the city’s entire student population, were not in school. (The numbers are hard to pin down. While a Louisiana state report that same year put the dropout rate at 5.7 percent, a 2013 report by the Louisiana Legislative Auditor found that the state’s DOE “no longer conducts on-site audits or reviews that help ensure the electronic data in its systems is accurate.”)

The premise of the New Orleans charter-school experiment is that charters can educate all children. However, the experience of kids like Lawrence Melrose, another Sci Academy student, does not support that claim. Now 18, Lawrence’s life is a testament to both high levels of social dysfunction, including poverty and violence, and the inability of some charter schools to meet the needs of the most disadvantaged kids.

It is hard to know when Lawrence’s life began to spin out of control. It may have been when his grandmother who raised him was diagnosed with cancer and he began shuttling back and forth between Georgia, where the family moved after Hurricane Katrina, and his great-uncle Shelton Joseph’s house in New Orleans. It may have been during a basketball game, near his great-uncle’s house, on a hot August day of his 14th year, when another kid shot him in the back, nearly killing him. Or it may have been during his dizzying spin through half a dozen struggling RSD schools in the two years before he enrolled at Sci Academy.

During the weeks Lawrence spent at Children’s Hospital recovering from his gunshot wound, a report on his neuropsychological state concluded that Lawrence “appears to have the skills necessary to be a productive member of society,” but also that he should continue to receive “special-education services at the highest level possible.”

A year later, in 2010, Lawrence enrolled as a freshman at Sci Academy; he had spent two years—with multiple suspensions and expulsions—in the New Orleans system. His first months at Sci Academy were rocky. When the school celebrated Marcovitz’s appearance on The Oprah Winfrey Show at the church next door, Lawrence was not there; he was kept back in the school’s office.

In 2010 Lawrence became one of 10 plaintiffs in a lawsuit filed by the Southern Poverty Law Center against the Louisiana Department of Education, charging that the city’s fragmented education system had resulted in “systemic failures to ensure that students with disabilities have equal access to educational services and are protected from discrimination.” (The SPLC has since petitioned the court to certify the case as a class action suit.)

Lawrence spent less and less time at school. At 17, he was arrested for armed robbery; repeatedly found incompetent to stand trial, Lawrence spent a year and a half in jail. He finally pleaded guilty and agreed to a 10-year sentence, minus time already served.

On a recent Saturday morning, Lawrence sat behind a plexiglas barrier at Orleans Parish Prison, his jaw slightly swollen after it was broken in a jailhouse beating. Lawrence was wearing a bulky, sleeveless “suicide” smock that also covered a knife wound from another incident in the jail. Lawrence isn’t really a suicide risk, explained Chaseray Griffin, Lawrence’s SPLC advocate; placement on the suicide ward, where the inmate’s clothes are taken away, was his best chance of staying safe until he is moved to a state penitentiary.

Although Lawrence has taken classes in prison, he has not graduated. Yet, when the state of Louisiana calculates its dropout statistics, Lawrence and other incarcerated teens are not included.

It is tempting to look at Lawrence as an exception. But his case points to problems not only with the quality of individual schools in New Orleans, but also with government oversight and the incentive structure of charter schools. “State monitoring has virtually stopped,” says Margaret Lang, who retired last year as director of intervention services at the RSD. “The kids who get churned the most are those with the most disabilities and challenges.”.

In New Orleans, critics argue that the pressure to show high test scores and get kids into college, combined with the broad leeway given to charter schools to suspend and expel students, means the “difficult to teach” kids have been effectively abandoned. “New ideas on how to teach disruptive and unmotivated students have not emerged from charter schools,” charges Barbara Ferguson, a former superintendent of public schools in New Orleans and a founder of Research on Reforms. “Whether the difficult-to-teach high school students are expelled by charter schools or whether they attended schools closed by the RSD, they are an outcast group, thrown into an abyss … Neither the RSD nor the state Department of Education tracks these students to determine if they ever enter another high school.”

But even for students who don’t fall through the cracks or get expelled, it bears asking: have the pressures and incentive systems surrounding charter schools taken public education in the direction we want it to go? Anthony Recasner, a partner in founding New Orleans Charter Middle School and FirstLine, is visibly torn between his hopes for the New Orleans charter experiment and his disappointment in the distance that remains between today’s no-excuses charter-school culture and the movement’s progressive roots. “Education should be a higher-order exploration,” says Recasner, a child psychologist who left FirstLine in 2011 to become CEO of Agenda for Children, a children’s advocacy organization. The typical charter school in New Orleans “is not sustainable for the adults, not fun for kids,” says Recasner, who is one of the few African-American charter leaders in New Orleans; his own experience as a poor child raised by a single parent mirrors that of most students in the charter schools. “Is that really,” he asks, “what we want for the nation’s poor children?”

This article was reported in partnership with the Investigative Fund at the Nation Institute. It was also made possible by funding from the New World Foundation’s Civic Opportunities Initiative Network.

Leave A Comment