How we remember the history of school segregation can be a mystery. What we do and have done to change our history – that is the greater mystery.

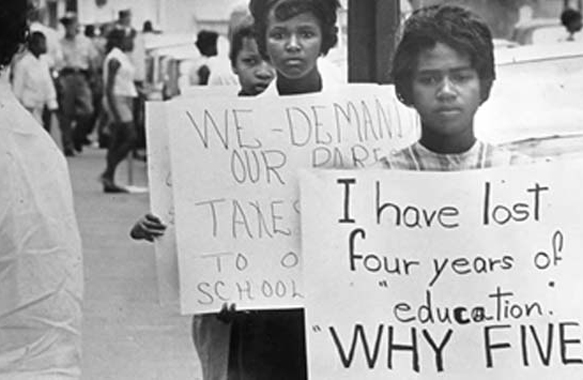

When I tell people here in New York City — friends, students, acquaintances, strangers who sit next to me on the train and cabdrivers who don’t slide the partition closed — that I have written a book about Prince Edward County, Virginia, which closed its public schools for five years (1959-64) rather than desegregate them, the usual reaction is visible disdain, followed by pointed commentary or resigned grumbling about the insanity of white Southerners. This response has not surprised me when it comes from the sort of financially comfortable liberals that SUV conservatives love to mock for their hypocrisy.

But this disgust for the retrograde South has also come from many of my students at Lehman College, a City University of New York campus in the Bronx. Most of them are black or Latino, and many attended intensely segregated, poorly performing schools in some of the roughest neighborhoods in New York City. They, too, had been taught that the supposedly more enlightened North had never had any real problem with integration, their own experiences notwithstanding.

When we discuss the massive one-day protest over school segregation by New York City’s Black and Latino students in 1964 — the largest demonstration in American civil rights history — and the racially incendiary battle over community control of schools in Ocean Hill-Brownsville (Brooklyn) in the late 60s, many are stunned. They had only been taught about brave black protestors and vengeful whites in the South of the 1950s and 60s. “Why didn’t we learn about this in high school?” students have asked.

The effort to maintain racial dominance by white America respects no regional boundaries. This, of course, does not excuse Prince Edward County’s callous disregard for black schoolchildren, as most white kids attended segregated academies when public schools were closed. Jettisoning public education is certifiably loco, but passing such judgment encourages us to draw the curtains and turn away from what has happened, and continues to happen, in our own backyards. The move toward racial desegregation in schools, not to mention other steps toward racial equality, has been resisted at nearly every step by whites nationwide — only the tactics have varied.

Some localities attempted to circumvent court desegregation orders. Some drew Byzantine school districts that kept the poor and the brown in one set of schools, and more affluent whites in others. Some accepted racially diverse student bodies, but segregated students inside through devices such as tracking. Many families didn’t rely on the local government or school board to keep their schools homogenous; they simply moved to places where blacks and Latinos didn’t reside. And still do.

As noted in a recent New York Times editorial on Westchester County’s continued refusal to build affordable housing, despite agreeing to do so in a consent decree, “The struggle for racial integration is neither bygone nor exclusively Southern.” It is not enough to take verbal swipes at the low-hanging fruit: the segregated proms in Montgomery County, Georgia, or the hateful words of Don Imus or Mel Gibson. And it is surely not enough to dismiss segregation as something natural and inevitable.

For those of us who believe that a segregated United States cannot survive as we move closer to the time when less than half the nation is white, we must be proactive. This is not always easy. My wife, who is black, and I (white), have spent a lot of frustrating time trying to find a quality public school in Brooklyn that looks like America in all its racial and socioeconomic diversity. We feel fortunate to have our son enrolled in a school — 30 minutes away in another part of Brooklyn — that fits the bill. This is no heroic sacrifice for the cause of integration, but simply what we think is best for our son.

Ill-conceived efforts to drive “undesirables” out of our towns or states (through harsh anti-immigrant laws) or prevent qualified people from voting (under the transparent guise of preventing voter fraud) will not reverse the demographic changes that continue to unfold in our nation. Ultimately, a more inclusive United States is the way to move forward. We can’t be satisfied to talk about this idea as an abstract goal that we share with our friends in self-congratulatory tones, as those with a conflicting vision of America’s future pursue policies to cement segregation in our voting booths, schools and neighborhoods.

Christopher Bonastia is an Associate Professor of Sociology, Lehman College

Originally Published as How Different Do Schools Look Today 50 Years After Prince Edward County, Virginia?

Leave A Comment