By Eric Westervelt | Originally Published at National Public Radio. November 21, 2013 5:15 PM | Listen to the story

Photograph; Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Corbett, a Republican, cut more than $1 billion from the state’s K-12 budget, which hit the state-controlled Philadelphia district hardest.

This is the second in a three-part report on Philadelphia schools in crisis.

Philadelphia’s Center City area sparkles with new restaurants, jobs and money. After declining for half a century, the city’s population grew from 2006 to 2012.

But for people living in concentrated poverty in large swaths of North and West Philadelphia, the Great Recession only made life harder.

The overall poverty rate in the city dipped slightly in 2012 to 28 percent. But the number of Philadelphians needing food stamps rose last year, and the child poverty rate in the city still hovers near 40 percent.

At Julia de Burgos Elementary School in North Philly, for example, almost every child lives at or below the federal poverty line.

The public school situation in Philadelphia is grim. The district is broke. The governor cut more than $1 billion from the state’s K-12 budget, which hit the state-controlled Philadelphia district hardest.

At the school year’s start, the district laid off thousands of employees, cut programs and services, and kept 23 underpopulated city schools closed this year. De Burgos just absorbed some 250 kids, an upheaval that’s still in progress. That’s put enormous strain on students, parents and teachers — especially when you throw in persistent poverty. Philadelphia’s rate of deep poverty is 12.9 percent, the highest among the largest U.S. cities, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

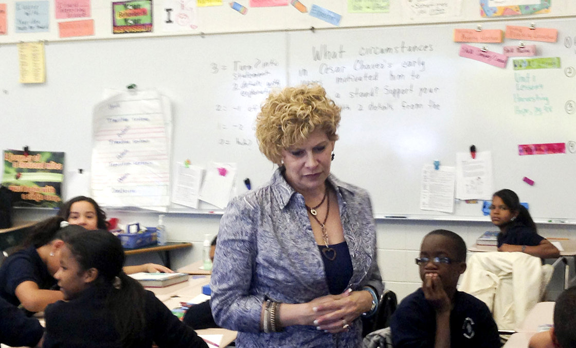

Sixth-grade teacher Gail Kantor is teaching her 13th year at de Burgos. She says she has had to increase out-of-pocket buying for her students.

“Clothing, books, all of the school supplies, backpacks,” Kantor says. “And you see some kids that are really suffering. Some kids don’t ever have a dime. They have one pencil, they have a spiral book, and they don’t have any of the supplies.”

Other teachers say they’ve had to bring in cleaning supplies — even toilet paper.

But lots of nonmaterial things gnaw at Kantor: She says some parents, many of them single moms, seem overwhelmed and disengaged. Kantor says she knows they’re stressed out and tries to reach out by phone, but is too often left discouraged.

“Number’s already wrong. They were already disconnected. People are sending their children to school without a phone number you can reach them,” she says.

Julia de Burgos Elementary teacher Gail Kantor, shown here in her sixth-grade class, says she buys things like clothing, books and school supplies for her students with her own money. “Some kids don’t ever have a dime,” she says.

Hillary Linardopoulos taught kindergarten and third grade at de Burgos for the last nine years. She’s currently on leave working for the teacher’s union. “When people aren’t living this situation every day and teaching kids who have such great needs every single day and seeing what it actually looks like, it’s hard to understand how severe the situation is and how difficult it is for a parent to raise a kid in poverty,” she says.

Poverty, Hunger, Education

Every child at de Burgos gets access to free breakfast and a free lunch at school. The principal says almost all take part.

Studies show the many ways poverty undermines learning: Lower-income kids enter kindergarten with poorer language skills than kids from middle- and upper-income homes.

They can’t concentrate as well, and children who are food insecure don’t perform as well on math and language arts tests. They don’t do as well in school.

~ Mariana Chilton of Drexel University’s School of Public Health

“They can’t concentrate as well, and children who are food insecure don’t perform as well on math and language arts tests.

Chilton says that at the height of the Great Recession, nearly half of all families with kids in this city reported “food hardship” — or increased hunger. She says the research is overwhelming: Poverty and hunger undermine children’s cognitive, social and emotional development.

“They also have a hard time getting along with their peers and with their teachers,” she says, “and so it’s strongly related to how well a child can do in school.”

Some parents in the swaths of concentrated poverty in North and West Philadelphia consistently don’t have enough for food, heat, rent, running water or electricity. That often means their kids can’t do homework, think or read in a comfortable place. Neighborhood violence and crime only add to their sense of vulnerability.

“It creates a certain kind of desperation and distrust among neighbors and among school administrators. And it’s a sense of being abandoned by our most important institutions,” Chilton says. “It’s a sense of being abandoned by the powers that be in the city of Philadelphia.”

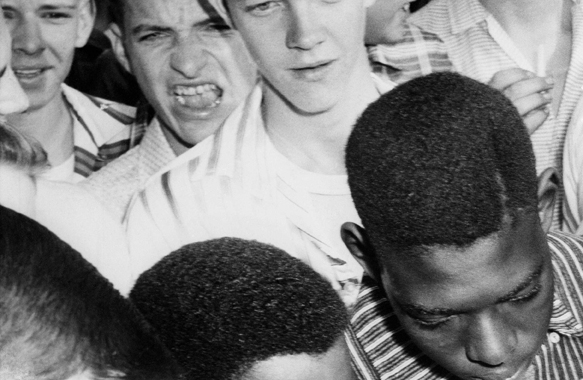

Over time, Philadelphia’s enduring poverty has exacerbated de facto segregation. Education historian Diane Ravitch says Philadelphia and other big, urban school systems in America too often fail to look at school crises — and solutions — holistically, and fail to link poverty and racial and income inequality with school performance.

“That is not just the elephant in the room — that is the biggest scandal in our country today,” she says. “We don’t want to talk about poverty, and the people who call themselves reformers say, ‘Poverty’s just an excuse for bad teachers.’ That’s their way of saying, ‘Let’s not talk about poverty.’ The whole state of Pennsylvania should be ashamed about what’s happening in Philadelphia today.”

People don’t want to talk about poverty, she says, because it’s too big and too ugly.

Nationally, the school achievement gap by income has widened substantially in the past 30 years, according to Sean Reardon of Stanford University. His work shows that economic inequality now exceeds racial inequality in its effect on education outcomes.

‘I’m Tired Of This’

Shearine McGhee, 34, is struggling to keep it all together: She has three kids, ages 1, 5 and 8. The father of the youngest child took off, and the father of the other two kids is in prison. McGhee gets food stamps, and for her youngest, food help from the federal assistance program WIC, or Women, Infants and Children.

“I do rely on it. Sometimes when you run out of food stamps or you run out of food, you still got your WIC checks,” she says.

She now works at a WIC office as a nutritionist’s assistant. She makes $8.97 an hour — barely enough, she says, to get by. McGhee says she and other single moms depend on the free food from public schools.

“When them kids come to school, you don’t know if they have food in their refrigerator, or if their mom is around — she could be on drugs or whatever or not even there,” she says. “What are they eating? We don’t know once they leave school.”

What McGhee hopes for is good public schools for her kids, and, someday, a food truck selling her homemade soul food. “I wanna be an entrepreneur,” she says. “I’m tired of this.”

Leave A Comment