By Paul L. Thomas, Ed.D. | Originally Published at The Becoming Radical. December 17, 2013

Rep. Andy Patrick, R-Hilton Head Island (SC), has made two flawed claims recently, one about leadership and another about teacher evaluation (“S.C. lawmaker proposes teacher evaluation plan,” Charleston Post and Courier, December 10, 2013).*

First, and briefly, Patrick asserts that SC needs leadership for superintendent of education, discounting the importance of experience or expertise. As I will address below, Patrick’s lack of experience and expertise is, ironically, evidence that leadership is not enough. In fact, leadership begins with experience and expertise; it doesn’t replace those essential qualities.

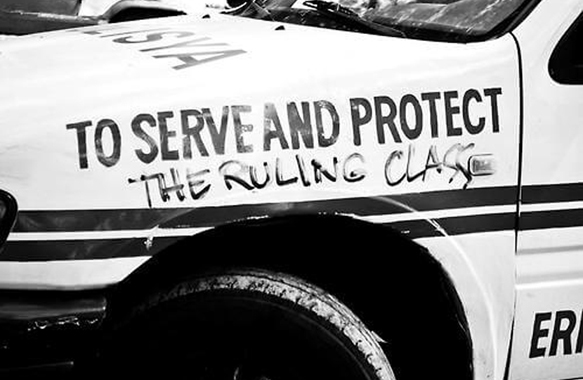

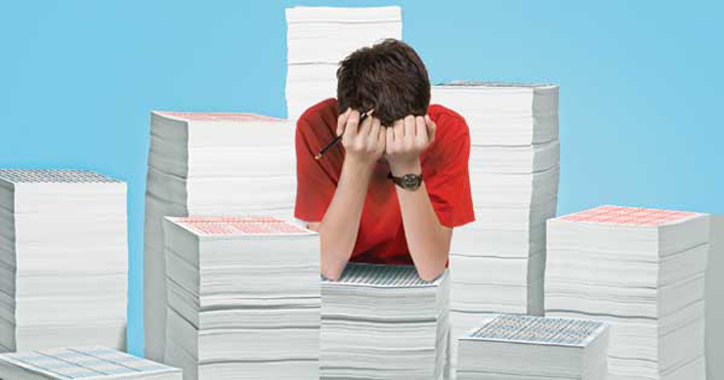

Next, and more importantly, Patrick’s and current Superintendent Mick Zais’s pursuit of test-based teacher evaluation reform is deeply flawed and discredited by research on value added methods (VAM) of evaluating teachers.

Endorsing VAM-heavy teacher evaluation joins grade retention, charter schools, and Common Core as a series of policy decisions in SC that are countered by the research base—resulting in a tremendous waste of time and funding that should be better spent for our students and our state.

For example, Edward H. Haertel’s Reliability and validity of inferences about teachers based on student test scores (ETS, 2013) now offers yet another analysis that details how VAM fails, again, as a credible policy initiative. Haertel’s analysis offers the following:

- First, Haertel addresses the popular and misguided perception that teacher quality is a primary influence on measurable student outcomes. As many researchers have detailed, teachers account for about 10% of student test scores. While teacher quality matters, access to experienced and certified teachers as well as addressing out-of-school factors dwarf narrow measurements of teacher quality.

- Next, Haertel confronts the myth of the top quintile teachers, outlining three reasons that arguments about those so-called “top” teachers’ impact are exaggerated.

- Haertel also acknowledges the inherent problems with test scores and what VAM advocates claim they measure—specifically that standardized tests create a “bias against those teachers working with the lowest- performing or the highest performing classes” (p. 8).

- The next two sections detail the logic behind VAM as well as the statistical assumptions in which VAM is grounded, laying the basis for Haertel’s main assertion about using VAM in high-stakes teacher evaluations.

- The main section of the report reaches a powerful conclusion that matches the current body of research on VAM:

These 5 conditions would be tough to meet, but regardless of the challenge, if teacher value-added scores cannot be shown to be valid for a given purpose, then they should not be used for that purpose.

So, in conclusion, VAM may have a modest place in teacher evaluation systems, but only as an adjunct to other information, used in a context where teachers and principals have genuine autonomy in their decisions about using and interpreting teacher effectiveness estimates in local contexts. (p. 25)

First, they attend to what teachers actually do — someone with training looks directly at classroom practice or at records of classroom practice such as teaching portfolios. Second, they are grounded in the substantial research literature, refined over decades of research, that specifies effective teaching practices….Third, because sound teacher evaluation systems examine what teachers actually do in the light of best practices, they provide constructive feedback to enable improvement. (p. 26)

Haertel’s concession that VAM has a “modest” place in teacher evaluation is no ringing endorsement, but it certainly refutes the primary—and expensive—role that VAM is playing in proposals to reform teacher evaluation in SC and across the U.S.

Would SC benefit from focusing on teacher quality—as well as insuring all children have equitable access to experienced and certified teachers? Absolutely.

But current calls by leaders with no experience or expertise in education are failing that possibility by rushing to implement policy that is contradicted by a growing body of research discounting the value of VAM as a key element of teacher evaluation.

SC students, teachers, and schools cannot afford doubling-down on a failed test-based education culture, and certainly, SC cannot afford more leadership without expertise, which is what Representative Patrick is offering.

* Submitted to and unpublished in, so far, Charleston Post and Courier.

Leave A Comment