Illustration; post typography

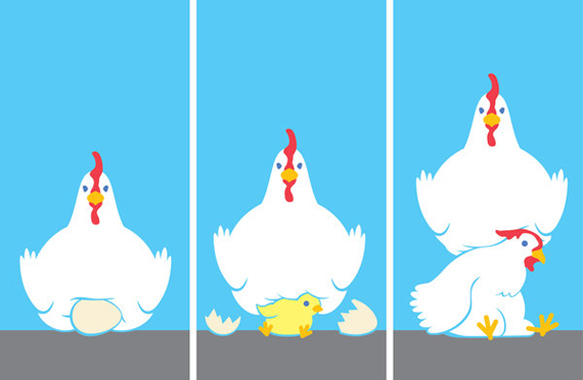

You might have mused about how you helped and how you have hurt your children. Perhaps you have asked yourself if you have done too much or if you did too little. Can we save a child who has gone astray? Is it possible to rescue our children? Might it be that if we reflect on how we would feel if someone wanted to save “me” we would do neither? Could it be that there is a delicate balance, one that is essential to keep in mind? Helping can hurt; not helping can help.

When Helping Hurts

AMERICAN parents are more involved in our children’s lives than ever: we schedule play dates, assist with homework and even choose college courses.

We know that all of this assistance has costs — depleted bank balances, constricted social lives — but we endure them happily, believing we are doing what is best for our children.

What if, however, the costs included harming our children?

That unsettling possibility is suggested by a paper published in February in the American Sociological Review. The study, led by the sociologist Laura T. Hamilton of the University of California, Merced, finds that the more money parents spend on their child’s college education, the worse grades the child earns.

A separate study, published the same month in the Journal of Child and Family Studies and led by the psychologist Holly H. Shiffrin at the University of Mary Washington, finds that the more parents are involved in schoolwork and selection of college majors — that is, the more helicopter parenting they do — the less satisfied college students feel with their lives.

Why would parents help produce these negative outcomes? It seems that certain forms of help can dilute recipients’ sense of accountability for their own success. The college student might think: If Mom and Dad are always around to solve my problems, why spend three straight nights in the library during finals rather than hanging out with my friends?

And there is no reason to believe that parents and children have cornered the market on these dynamics. Indeed, “helicopter helping” should yield similar consequences in virtually any relationship — with spouses, friends, co-workers — in which one person can help another.

We tested this idea in a 2011 experiment, published in the journal Psychological Science, in which we randomly assigned American women who cared a lot about their health and fitness to think about how their spouse was helpful, either with their health and fitness goals or for their career goals. Women who thought about how their spouse was helpful with their health and fitness goals became less motivated to work hard to pursue those goals: relative to the control group, these women planned to spend one-third less time in the coming week pursuing their health and fitness goals.

Before getting carried away on the risks of helping, though, it’s important to highlight the obvious, that helping others achieve their goals has important benefits, for both parties. Responsive, supportive relationships are the foundation of a healthy and productive life.

And therein lies the problem: how can we help our children (and our spouses, friends and co-workers) achieve their goals without undermining their sense of personal accountability and motivation to achieve them?

The answer, research suggests, is that our help has to be responsive to the recipient’s circumstances: it must balance their need for support with their need for competence. We should restrain our urge to help unless the recipient truly needs it, and even then, we should calibrate it to complement rather than substitute for the recipient’s efforts.

The good news is that people seem to be adept at understanding when others need help, as shown in a fascinating observational study of barroom brawls. This study, led by the sociologist Michael J. Parks of Penn State and published online in March in the journal Aggressive Behavior, showed that bystanders are especially likely to intervene to end the brawl to the extent that the brawlers are intoxicated. That is, observers stepped in to help precisely when that help was most needed.

Although appropriating recipients’ self-control efforts can be essential when their self-control is compromised, as when they are drunk, a better approach in most situations is to calibrate one’s help to complement the recipient’s own efforts. In a 2007 study published in the Journal of Personal Social Psychology, the Carnegie Mellon psychologist Brooke Feeney videotaped married couples as they discussed one partner’s personal goals, like switching jobs or developing a new hobby. When the spouses of these goal pursuers were receptive to being relied upon (as judged by trained coders) but did not impose their help, the goal pursuers behaved more independently in the pursuit of their goal and, most important, were more likely to achieve it over the next six months.

In short, although much remains to be investigated, the findings thus far suggest that providing help is most effective under a few conditions: when the recipient clearly needs it, when our help complements rather than replaces the recipient’s own efforts, and when it makes recipients feel that we’re comfortable having them depend on us.

So yes, by all means, parents, help your children. But don’t let your action replace their action. Support, don’t substitute. Your children will be more likely to achieve their goals — and, who knows, you might even find some time to get your own social life back on track.

Eli J. Finkel is a professor of psychology at Northwestern University. Grainne M. Fitzsimons is an associate professor of management and an associate professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University.

A version of this op-ed appeared in print on May 12, 2013, on page SR12 of the New York edition with the headline: When Helping Hurts.

Leave A Comment