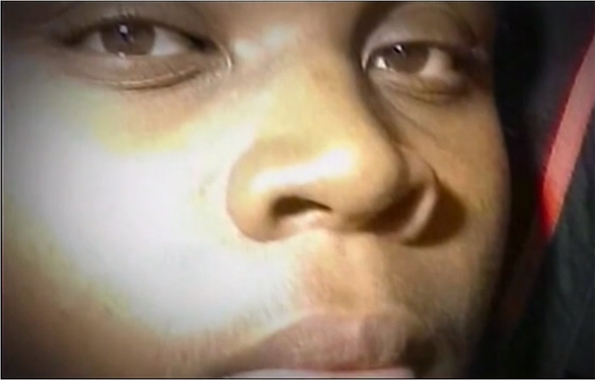

Photograph; Michael Brown. Hershel Johnson, a friend of Brown’s since middle school remembers. “He said he wasn’t going to end up like some people on the streets. He was going to get an education. He was going to make his life a whole a lot better.”

By Charles M. Blow | Originally Published at The New York Times. August 13, 2014

The killing of Michael Brown has tapped into something bigger than Michael Brown.

Brown was the unarmed 18-year-old black man who was shot to death Saturday by a policeman in Ferguson, Mo. There are conflicting accounts of the events that led to the shooting. There is an investigation by local authorities as well as one by federal authorities. There are grieving parents and a seething community. There are swarms of lawyers and hordes of reporters. There has been unrest. The president has appealed for reflection and healing.

There is an eerie echo in it all — a sense of tragedy too often repeated. And yet the sheer morbid, wrenching rhythm of it belies a larger phenomenon, one obscured by its vastness, one that can be seen only when one steps back and looks from a distance and with data: The criminalization of black and brown bodies — particularly male ones — from the moment they are first introduced to the institutions and power structures with which they must interact.

Earlier this year, the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights released “the first comprehensive look at civil rights from every public school in the country in nearly 15 years.” As the report put it: “The 2011-2012 release shows that access to preschool programs is not a reality for much of the country. In addition, students of color are suspended more often than white students, and black and Latino students are significantly more likely to have teachers with less experience who aren’t paid as much as their colleagues in other schools.”

Attorney General Eric Holder, remarking on the data, said: “This critical report shows that racial disparities in school discipline policies are not only well-documented among older students, but actually begin during preschool.”

But, of course, this criminalization stalks these children throughout their school careers.

As The New York Times editorial board pointed out last year: “Children as young as 12 have been treated as criminals for shoving matches and even adolescent misconduct like cursing in school. This is worrisome because young people who spend time in adult jails are more likely to have problems with law enforcement later on. Moreover, federal data suggest a pattern of discrimination in the arrests, with black and Hispanic children more likely to be affected than their white peers.”

A 2010 report by the Southern Poverty Law Center found that while the average suspension rate for middle school students in 18 of the nation’s largest school districts was 11.2 percent in 2006, the rate for black male students was 28.3 percent, by far the highest of any subgroup by race, ethnicity or gender. And, according to the report, previous research “has consistently found that racial/ethnic disproportionality in discipline persists even when poverty and other demographic factors are controlled.”

And these disparities can have a severe impact on a child’s likelihood of graduating. According to a report from the Everyone Graduates Center at Johns Hopkins University that looked at Florida students, “Being suspended even once in 9th grade is associated with a two-fold increase in the risk for dropping out.”

Black male dropout rates are more than one and a half times those of white males, and when you look at the percentage of black men who graduate on time — in four years, not including those who possibly go on to get G.E.D.s, transfer to other schools or fail grades — the numbers are truly horrific. Only about half of these black men graduate on time.

Now, the snowball is rolling. The bias of the educational system bleeds easily into the bias of the criminal justice system — from cops to courts to correctional facilities. The school-to-prison pipeline is complete.

A May report by the Brookings Institution found: “There is nearly a 70 percent chance that an African American man without a high school diploma will be imprisoned by his mid-thirties.”

This is in part because trending policing disparities are particularly troubling in places like Missouri. As the editorial board of The St. Louis Post-Dispatch pointed out this week: “Last year, for the 11th time in the 14 years that data has been collected, the disparity index that measures potential racial profiling by law enforcement in the state got worse. Black Missourians were 66 percent more likely in 2013 to be stopped by police, and blacks and Hispanics were both more likely to be searched, even though the likelihood of finding contraband was higher among whites.”

And this is the reality if the child actually survives the journey. That is if he has the internal fortitude to continue to stand with the weight on his shoulders. That is if he doesn’t find himself on the wrong end of a gun barrel. That is if his parents can imbue in him a sense of value while the world endeavors to imbue in him a sense of worthlessness.

Parents can teach children how to interact with authority and how to mitigate the threat response their very being elicits. They can wrap them in love to safeguard them against the bitterness of racial suspicion.

It can be done. It is often done. But it is heartbreaking nonetheless. What psychic damage does it do to the black mind when one must come to own and manage the fear of the black body?

The burden of bias isn’t borne by the person in possession of it but by the person who is the subject of it. The violence is aimed away from the possessor of its instruments — the arrow is pointed away from the killer and at the prey.

It vests victimhood in the idea of personhood. It steals sometimes, something precious and irreplaceable. It breaks something that’s irreparable. It alters something in a way that’s irrevocable.

We flinchingly choose a lesser damage.

But still, the hopelessness takes hold when one realizes that there is no amount of acting right or doing right, no amount of parental wisdom or personal resilience that can completely guarantee survival, let alone success.

Brown had just finished high school and was to start college this week. The investigation will hopefully clarify what led to his killing. But it is clear even now that his killing occurred in a context, one that we would do well to recognize.

Brown’s mother told a local television station after he was killed just weeks after his high school graduation: “Do you know how hard it was for me to get him to stay in school and graduate? You know how many black men graduate? Not many. Because you bring them down to this type of level, where they feel like they don’t got nothing to live for anyway. ‘They’re going to try to take me out anyway.’ ”

Originally Titled and Printed in the New York Times as “Michael Brown and Black Men”

Leave A Comment