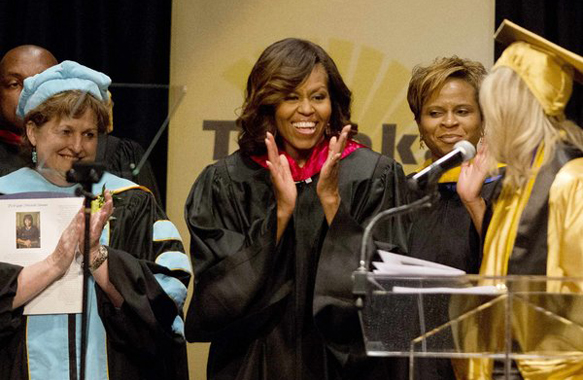

Michelle Obama attended the “Senior Recognition Day” event with high school students in Topeka, Kan., on Friday. | Credit Sait Serkan Gurbuz/Reuters

By Sheryl Gay Stolberg | Originally Published at The New York times. May 16, 2014

TOPEKA, Kan. — Sixty years after the Supreme Court outlawed “separate but equal” schools for blacks and whites, civil rights advocates say American schools are becoming increasingly segregated, while the first lady, Michelle Obama, lamented that “many young people are going to schools with kids who look just like them.”

“Today, by some measures, our schools are as segregated as they were back when Dr. King gave his final speech,” Mrs. Obama told 1,200 graduating high school seniors Friday here in the city that gave rise to the landmark Brown v. Board of Education case.

In a speech that was part commencement address, part policy pronouncement and part journey into her own past, Mrs. Obama said that Brown’s advances were being reversed. “Many districts in this country have actually pulled back on efforts to integrate their schools, and many communities have become less diverse,” she said, leading to schools that are less diverse.

“And too often,” Mrs. Obama said, “those schools aren’t equal, especially ones attended by students of color which too often lag behind.”

“We have slowly and very steadily slipped backward,” said Catherine E. Lhamon, the department’s assistant secretary for civil rights. “All over the country we are seeing more and more racially segregated schools.”

Here in Kansas, there is intense debate over whether the state is living up to Brown’s promise. An alliance of school districts has sued the state, contending that current financing for schools is inadequate and is disproportionately hurting schools in low-income, minority districts.

The State Supreme Court recently ordered the Legislature to restore special aid for poor districts. Gov. Sam Brownback said in a brief interview on Friday that he agreed with the court’s decision. “It needs to be fixed,” he said.

But Wade Henderson, president of the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights in Washington, said Friday that funding systems like that in Kansas “are relegating millions of primarily black and brown children into schools that are separate, unequal and inadequate.”

Saturday marks 60 years to the day that the Supreme Court decided Brown, a case whose lead plaintiff was Oliver L. Brown, a part-time pastor and shop welder for the Santa Fe Railroad who wanted his eldest daughter, Linda, to attend integrated schools.

In Washington on Friday evening, President Obama observed the anniversary of the Brown decision by meeting with families of the plaintiffs. Linda Brown and her younger sister, Cheryl Brown Henderson, as well as two of the lawyers in the case, planned to attend.

“It’s our first African-American president, something that many people involved in Brown didn’t think they would live to see,” Mrs. Brown Henderson said in an interview this week, calling the visit “a manifestation of what they worked for.”

Mrs. Obama spent the afternoon touring the Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site in Topeka. The two-story brick schoolhouse, once a school for blacks only, is now a civil rights museum and education center, and the first lady held a round-table discussion there with high school students from poor neighborhoods who dream of going to college.

“What are your hopes, how do you think about college, what do you think about life there?” she asked them. “What are some of the challenges that you face?”

Earlier in the day, Governor Brownback visited the site, cutting a ribbon on a newly renovated kindergarten classroom that has been restored to look as it did during the 1950s.

“Separate but equal ends here,” Mr. Brownback said.

People in Topeka have strong feelings about the Brown case; some of those who attended Mr. Brownback’s ribbon cutting on Friday had attended segregated schools here. Among them was Dale Cushinberry, a retired school principal, who recalls being bused as a child to a school outside his own neighborhood.

“Our neighborhood was integrated,” Mr. Cushinberry said. “We played in the park together, and played ball on weekends, and then on Monday we would get on a yellow school bus and they” — his white playmates — “would walk down the street” to the neighborhood school.

“After Brown,” he said, “we just walked to school together.”

For Mrs. Obama, too, the visit was personal. She was born in Chicago at a time when public schools were still resisting integration. By the time she entered high school, the city — under pressure from the federal government — opened an integrated magnet school for high achievers, which Mrs. Obama credits with setting her on a path to Princeton and Harvard.

She told the students in Topeka that when she was feeling discouraged, she liked to “take a step back and remind myself” of all the progress she had seen.

“I think about my mother, who, as a little girl, went to segregated schools in Chicago and felt the sting of discrimination,” she said. “I think about my husband’s grandparents, white folks born and raised right here in Kansas — products themselves of segregation,” who helped raise a biracial grandson.

“And then,” Mrs. Obama said, “I think about how that child grew up to be the president of the United States, and how today, that little girl from Chicago is helping to raise her granddaughters in the White House.”

A version of this article appears in print on May 17, 2014, on page A14 of the New York edition with the headline: Mrs. Obama, in Speech, Cites Growing Divisions.

Leave A Comment