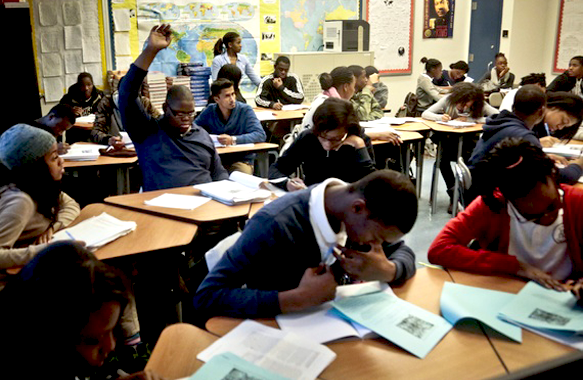

Photograph; Bebeto Matthews/AP Images

By Paul L. Thomas, Ed.D. | Originally Published at The Becoming Radical. January 22, 2014

Students Should Be Tested More, Not Less by Jessica Lahey is not a compelling case to test students more, but another example of journalism failing to represent accurately a relatively limited study related to education.

Several aspects of the article reveal that the title and apparent claim of the need for more testing are misleading:

Henry L. Roediger III, a cognitive psychologist at Washington University, studies how the brain stores, and later retrieves, memories. He compared the test results of students who used common study methods—such as re-reading material, highlighting, reviewing and writing notes, outlining material and attending study groups—with the results from students who were repeatedly tested on the same material. When he compared the results, Roediger found. “Taking a test on material can have a greater positive effect on future retention of that material than spending an equivalent amount of time restudying the material.” Remarkably, this remains true “even when performance on the test is far from perfect and no feedback is given on missed information.”

And to be fair, this is the actual abstract of the study discussed above:

A powerful way of improving one’s memory for material is to be tested on that material. Tests enhance later retention more than additional study of the material, even when tests are given without feedback

[emphasis added]. This surprising phenomenon is called the testing effect, and although it has been studied by cognitive psychologists sporadically over the years, today there is a renewed effort to learn why testing is effective and to apply testing in educational settings. In this article, we selectively review laboratory studies that reveal the power of testing in improving retention [emphasis added] and then turn to studies that demonstrate the basic effects in educational settings. We also consider the related concepts of dynamic testing and formative assessment as other means of using tests to improve learning. Finally, we consider some negative consequences of testing that may occur in certain circumstances, though these negative effects are often small and do not cancel out the large positive effects of testing. Frequent testing in the classroom may boost educational achievement at all levels of education.Not to trivialize the study, but in short, the research associates “learning” with retention (memorization), and assumes a relatively direct correlation between test scores and the narrow view of learning as retention. In other words, if you want to raise summative test scores of retention, a series of smaller (and formative) tests are more effective in raising those scores than compared study strategies.

The problem with this “well, duh” study is that it remains trapped within the testing paradigm, even though the authors do concede (and then marginalize) problems with high-stakes testing and also briefly endorse the power of formative assessment: “the general procedure of using the results of classroom assessments as feedback for teachers to guide future instruction and also for students to guide their future studying” (p. 201).

This study, however, is not a compelling argument* as the title states for more testing.

In fact, it is an ideal opportunity to argue that we must move beyond retention, recall, and memorization as foundational to what counts as learning. We must also begin to reject that traditional testing formats (including selected-response formats in the classroom as well as standardized testing such as the SAT) are credible goals or evidence of learning.

Students should be tested less, and then not at all. Students should be offered opportunities to practice and perform whole and authentic activities (such as playing an instrument, creating a work of art, composing an essay, designing a budget for a project) during class time instead of preparing for and taking a battery of narrow assessments. Additionally, students need ample teacher feedback, and not grades, as part of drafting and revision processes surrounding those activities.

Retention and enhanced memory come from authentic engagement with real behaviors that students want to perform; memorization need not precede authentic displays of understanding, and must not be a primary proxy for learning. Ultimately, memorization is not deep learning, and testing limits, and never enhances deep learning. Test scores also misrepresent student learning, teacher impact, and school quality.

Lahey’s article and the research on testing do offer valuable concerns about high-stakes associated with testing, and lends credibility to formative assessment, but both in the end remain trapped within the failed testing paradigm that needs to be lessened and then rejected entirely.

* Broadly, the authors ignore entirely issues related to who decides what should be learned; in other words, critical educators tend to explore education not bound by the traditional testing paradigm within which this study resides like a bug trapped in amber. The narrow and static view of knowledge and learning is as problematic as the idealized view of testing that the study fails to challenge.

Leave A Comment