By Paul L. Thomas, Ed.D. | Originally Published at The Becoming Radical. December 22, 2013

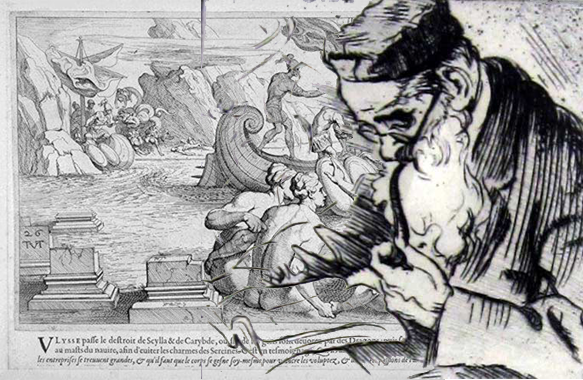

In our popular discourse, we are prone to say we are caught between a rock and a hard place, a veiled allusion to Homer’s Scylla and Charybdis.

For K-12 public school teachers over the past thirty years, our Scylla and Charybdis have been federal, state, district, and school mandates on one side and our own professional expertise and autonomy on the other as we navigate the rough waters of serving our students.

When Diane Ravitch spoke at my home university, she offered a talk to a small group in the afternoon and then attended an informal gathering before her main speech. Since she and I had become virtual friends through email and Twitter, this was the first time we met in person. I took that opportunity to introduce Diane to a former graduate student of mine who at the time was struggling in a “no excuses” environment at the high-poverty, majority-minority public school where she taught.

I explained this as I introduced the early-career teacher to Diane, who immediately looked up from signing her book to say, “Don’t lose your job. We need you in the classroom.”

Those of us at the university level—especially emeriti and tenured professors—have positions that are unlike those of K-12 teachers, especially K-12 teachers in Southern states that are right-to-work (non-tenure).

Having taught in public school in SC for 18 years before entering higher education for the last 13 years, I know those worlds well.

And so I immediately thought of Diane’s comment when Katie posted on my blog post, Supporting Common Core Is Supporting Entire Reform Machine:

What suggestions do you have for productive resistance for those of us who have no choice but to work with it?

I also was forced to confront a hard lesson I learned when I was a co-instructor in the Spartanburg Writing Project. A new teacher, Dawn Mitchell, was in our summer institute, and once we confronted her with the tension between her first-year practices and best practice in literacy, she became the personification for me of the potential paralysis classroom practitioners face because of the Scylla and Charybdis of mandates and best practice—as well as the weight of teaching and blogging that is passionate and demanding themselves.

Dawn taught me that my role is to help teachers navigate the Scylla and Charybdis—not to reinforce the hard place of best practice. I now (thank you, Dawn) try to emphasize that teachers need to seek ways to incorporate one new best practice on Monday, but not to feel obligated to reinvent their classrooms wholesale tomorrow, and above all else, not to sacrifice themselves on the alter of nonconformity.

Now Katie has joined a long list of others who have taught me. As an apology (I should not be blogging in ways that contribute to the anxiety and pressure that K-12 teachers already feel) and an act of good faith to do better, let me answer her question:

- First, let’s all start with do not harm to children and students. If we start here, we can evaluate better how to navigate our practices under the stress of mandates and best practice.

- Be professional. K-12 teachers must be diligent about their professionalism when interacting with administration, colleagues, parents, and students. Part of that professionalism is knowing our fields. Let’s start with a powerful knowledge base of best practice, and then be prepared to show how mandates do and do not reflect that best practice. Too often, we start with the mandates; let’s flip that paradigm.

- Find or create a community of professionals, preferably within our schools but including wider communities such as forming a Facebook group, joining state and national professional organizations, committing or recommitting to graduate degrees or graduate courses. One of the most corrosive aspects of teaching is isolation. Isolation erodes your professionalism and feeds your anxiety as well as your distrust in yourself.

- Once you’ve found or created that community, take the time to do a careful and honest appraisal of what mandates are genuinely beyond your control to change and what mandates are open for how they are fulfilled. Start your efforts for reform with the latter. Few things are as harmful to our field of teaching than a misguided fatalism about what things we perceive as requirements of our teaching

- Seek ways to communicate with your administration that are professional and evidence-based. Share articles that highlight the need for best practice and the problems with mandates. Discussions with administration are best when they are between you and the administrator(s)—in other words, not public and not unannounced—allowing those with authority to consider your points without feeling as if that authority is being challenged. Begin to build a collegial atmosphere in your school, among teachers and among teachers and administrators.

- Be political in ways that will not jeopardize your job. Share research and best practice with parents and state-level representatives, especially those directly involved in education committees. Share that research with school board members. Teachers are our best hope for teaching everyone, not just the students in our classes.

- Create a public voice for yourself by blogging, Tweeting, and/or writing Op-Eds for local, state, and regional publications. With this, I urge caution. All K-12 teachers run some degree of risk by becoming a public voice, but I remain convinced that we must speak publicly. The challenge for each teachers is learning what works, what is safe, and then what you can do to increase the safe space for teachers’ public voices. Teachers need also to consider how to join the scholarly community by conducting classroom-based research and submitting work to scholarly journals—often a less dangerous avenue to creating a public voice.

- Offer alternatives to the practices you feel are misguided. Since mandates are the given in the field of teaching, we are not served well by simply discounting what is being done (even when we are right). What should we do instead and how will that be better? Can you share with colleagues and administration models of the alternatives you have implemented in your classroom, highlighting how those practices serve both best practice and mandates?

Few things will deteriorate a teacher’s passion more than the fatalism of conforming to mandates she/he feels are misguided. As with students, teachers need and deserve autonomy, voice, and action.

As a final real-world point: Some Common Core advocates have responded to me by stating that the math CC standards are better than what the state had before. My argument is that instead of advocating for CC, all teachers should be advocating for teacher autonomy and thus the professional embracing of best practice identified by our perspective fields—not mandated in public policy by non-teachers, and not linked to highs-stakes testing.

Education certainly needs reform, but that reform must come from the professionals and for the good of our students.

Katie, be true to your students, be true to yourself, and walk forward with patience and confidence. As Henry David Thoreau reminds us: “One is not born into the world to do everything but to do something.”

Choose your something with care, and don’t let it be a burden, but a call.

Leave A Comment