By Paul L. Thomas | Originally Published at The Becoming Radical. December 3, 2013, 2013

We have two recent commentaries that detail how schools and teachers fail students in the teaching of writing—one comes from a college student and the other, from a former teacher. While both reach the same conclusion about the teaching of writing, the reasons for those failures are in conflict, suggesting that we must consider whether schools and teachers are fumbling the teaching of writing, and then why.

Posted at Anthony Cody’s Living in Dialogue, a former Massachusetts student and current college student, Joan Brunetta, confronts the negative consequences of high-stakes accountability driven by standards and testing:

I am currently a student at Williams College, but I grew up in the public school system in Cambridge, MA and was among the first cohort of kids to have every single MCAS test administered, 3rd grade through 10th. Over the course of my years in the Cambridge public school system, I saw the scope of my education narrowed with increased testing, from a curriculum that valued student growth, experiences, and emotions, to one that was often cold and hard and moved on whether or not we were ready.

Brunetta’s experience should not be discounted as anecdotal since an analysis of twenty years of reform in her home state tends to reinforce her claim. As well, her message about how writing instruction distorted by standards and testing failed her is equally compelling:

In the years I attended high school, in which more focus was centered on testing, much more of our learning was directed toward tests. I wrote hardly anything but five-paragraph essays in high school English and history classes before 11th grade….

Some students said that they actually remember more of what they learned in elementary school than of the material they had learned just the last semester in high school, because those pieces of history or literature were taught in a context and were talked about, not glossed over and memorized quickly. Others noted that they had actually read and written more in elementary school than high school….

Here’s a rubric that my 7th and 8th grade teachers used for evaluating our essays. This is what real rigor looks like to me. Our papers were looked at as true pieces of writing, with respect to our ideas, our structure, and our use of language. If you compare this to the rubric for an MCAS essay or an AP essay (both of which apparently test for a “higher” level of critical thinking), the juxtaposition is truly laughable. I would particularly like to point out the 7/8th grade criteria for good organization: “The paper has a thoughtful structure that surfaces from the ideas, more than the ideas feeling constrained by the structure. Paragraphs and examples connect with fluid transitions when necessary to make the relationships between ideas clear. The organization is not predictable but artful and interesting in the way it supports the ideas.” (emphasis my own)

To do this in writing is hard. It is a challenge. It is what real writers do when they write engaging essays, books, and articles. In MCAS essays and all the essays we wrote to prepare for MCAS essays, using an unpredictable structure was wrong. To do anything but constrain your ideas by the structure was very wrong. When we learned essay writing in high school, we were often handed a worksheet, already set up in five paragraphs, telling you exactly where to put the thesis, the topic sentences, and the “hook.” In my freshman history class, I was told that each paragraph should have 5-9 sentences, regardless of the ideas presented in the paragraph. The ideas didn’t matter–structure reigned supreme. There is nothing wrong with learning how to write in a structured and clear way–for many students, having certain structures to rely on or start with is very helpful. But when testing was involved, all of our writing was reduced to a single, simple, and restrictive structure–simply because that structure is simpler (and therefore cheaper) to grade. It is important to note here that I have heard multiple college professors specifically tell all their well-trained, test-ready students never to use this structure in their writing.

Furthermore, in elementary school, we were taught to edit our writing (a skill totally missing from any MCAS standards and tests and generally lacking from high school); we wrote at least 2 or 3 drafts each time. At the end of the year, we created a portfolio presentation, which we gave to parents, teachers, and community members about how we had grown over the year, what we still needed to work on, and what our goals were for next year. Almost all of my writing practices and skills that I use each day in college –and even more so, the ability to evaluate my own work and see what I need to do in the next draft or on the next paper–come from my middle school years in a school that was not following the guidelines and was refusing to prep us for tests.

Again, Brunetta’s experience is one student’s story that is typical of how high school instruction in the U.S. has been decimated by accountability, standards, and testing. Applebee and Langer, in fact, have compiled a powerful examination of the exact experiences Brunetta details: Despite teachers being aware of a growing body of research on how best to teach writing (in ways Brunetta experienced in elementary and middle school), there remains a “considerable gap between the research currently available and the utilization of that research in school programs and methods” (LaBrant, 1947, p. 87), notably in writing instruction in schools today.

However compelling Brunetta’s story is, Robert Pondiscio shares Brunetta’s conclusion while offering a much different source of failing students in the teaching of writing:

Like so many of our earnest and most deeply humane ideas about educating children in general, and poor, urban children in particular, this impulse toward authenticity is profoundly idealistic, seductive, and wrong. I should know. I used to damage children for a living with that idealism.

I taught 5th grade at PS 277 in the South Bronx from several years. It was the lowest-performing school in New York City’s lowest-performing school district. We didn’t believe in the kind of literacy instruction practiced by New Dorp High School, as described by Peg Tyre in her piece, “The Writing Revolution.” It is not an overstatement to say that our failure to help students become good readers and writers is why I became a curriculum reform advocate.

Pondiscio has continued to blame authentic writing instruction as a failure, linking it to the same narrowing effect as accountability:

More recently the muscular brand of test-driven education reform that has come to dominate schooling has ill-served those purposes by hollowing out the curriculum further still. If a child reads on grade level and graduates by age 18 our schools will eagerly pronounce him or her educated and send them off into the world, with diminished agency, fewer options, and less opportunity than their affluent and better-educated brethren. We have conspired—all of us—to make them less than fully free.

This fundamental injustice upset me and upsets me still. I sometimes note that my progressive credentials were in good order until I became a teacher. The education I was trained to give to my students left them less than prepared for self-sufficiency and upward mobility. My complicity in allowing the scope of their education to be narrowed, whether by progressive ideals or test-driven accountability, robbed them of some measure of their liberty. Not just economic liberty, but freedom of thought and expression.

What, then, should we conclude from Brunetta and Poniscio in the context of what we know about best practice in teaching writing and how writing is being taught in K-12 schools?

First, we are clearly failing the teaching of writing, and as Hillocks warned (see Hillocks, 2003, and Hillocks, 2002), that failure is primarily driven by high-stakes accountability’s influence on the classroom.

As well, the increased high-stakes testing of writing, notably the SAT and ACT along with high-stakes state assessments linked to standards, has eroded effective writing instruction, as NCTE cautioned. A machine-scored writing is a harbinger for even more damage to be done to the teaching of writing.

The tension between Brunetta and Poniscio about authentic writing instruction remains both troubling and important. In order to understand how Brunetta and Poniscio could reach the same conclusion with such contradictions, we must examine Brunetta’s and Poniscio’s characterizations of authentic writing instruction, specifically workshop approaches to teaching writing. Brunetta’s description quoted above should be measured against this from Poniscio:

Every day, for two hours a day, I led my young students through Reader’s and Writer’s Workshop. I was trained not to address my kids as “students” or “class” but as “authors” and “readers.” We gathered “seed ideas” in our Writer’s Notebooks. We crafted “small moment” stories, personal narratives, and memoirs. We peer edited. We “shared out.” Gathered with them on the rug, I explained to my 10-year-olds that “good writers find ideas from things that happened in their lives.” That stories have “big ideas.” That good writers “add detail,” “stretch their words,” and “spell the best they can.”

Teach grammar, sentence structure, and mechanics? I barely even taught. I “modeled” the habits of good readers and “coached” my students. What I called “teaching,” my staff developer from Teacher’s College dismissed as merely “giving directions.” My job was to demonstrate what good readers and writers do and encourage my students to imitate and adopt those behaviors.

Two brief points from Brunetta and Poniscio offer a window into clarifying why Brunetta’s characterization of writing workshop is more accurate than Poniscio’s: Brunetta notes, “in elementary school, we were taught to edit our writing…; we wrote at least 2 or 3 drafts each time,” while Poniscio laments, “Teach grammar, sentence structure, and mechanics? I barely even taught.”

Poniscio has fallen victim to a common mischaracterization of authentic writing instruction, one that suggests no direct instruction occurs, particularly direct instruction addressing grammar, mechanics, and usage.

If Poniscio was doing no direct instruction, then, in fact, he did fail his students. But that failure cannot be laid at the feet of workshop or authentic writing instruction.

Workshop approaches to teaching writing authentically include direct and purposeful instruction addressing all aspects of writing, including grammar, mechanics, and usage; the issue has never been if we teach grammar, for example, but when and how.

Poniscio’s characterization of writing workshop is cartoonish, a simplistic distortion of a vibrant field that portrays the teaching of writing as complex and multi-faceted.

For example, Writing Next (2007) highlights “Eleven Elements of Effective Adolescent Writing Instruction”:

1. Writing Strategies, which involves teaching students strategies for planning, revising, and editing their compositions

2. Summarization, which involves explicitly and systematically teaching students how to summarize texts

3. Collaborative Writing, which uses instructional arrangements in which adolescents work together to plan, draft, revise, and edit their compositions

4. Specific Product Goals, which assigns students specific, reachable goals for the writing they are to complete

5. Word Processing, which uses computers and word processors as instructional supports for writing assignments

6. Sentence Combining, which involves teaching students to construct more complex, sophisticated sentences

7. Prewriting, which engages students in activities designed to help them generate or organize ideas for their composition

8. Inquiry Activities, which engages students in analyzing immediate, concrete data to help them develop ideas and content for a particular writing task

9. Process Writing Approach, which interweaves a number of writing instructional activities in a workshop environment that stresses extended writing opportunities, writing for authentic audiences, personalized instruction, and cycles of writing

10. Study of Models, which provides students with opportunities to read, analyze, and emulate models of good writing

11. Writing for Content Learning, which uses writing as a tool for learning content material (pp. 4-5)

These eleven elements in no way discredit direct instruction or addressing grammar, mechanics, and usage; again, teaching writing is about couching direct instruction within students being provided structured, authentic and whole experiences with multi-draft, original writing.

Poniscio’s misrepresentation of workshop isn’t unusual among educators who embrace teacher-centered and knowledge-based approaches to learning. Part of Poniscio’s position lies within his embracing grammar, for example, as a body of knowledge worth acquiring as an end to learning, not as a means to better writing.

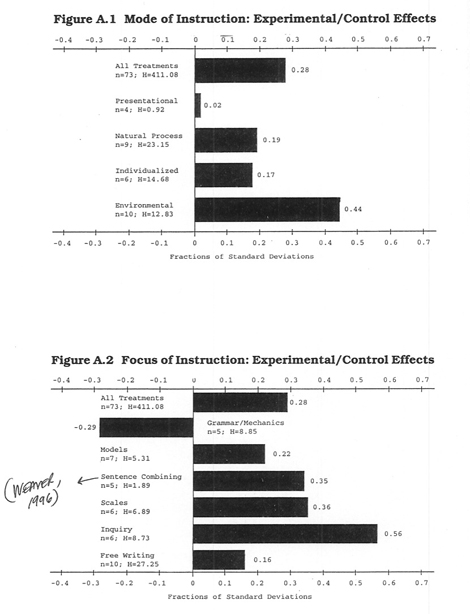

In writing instruction, grammar and other surface features (mechanics and usage) are important elements of a larger writing context, and research has shown (see Weaver, 1996, and Hillocks, 1995) that isolated direct grammar instruction neither helps students acquire grammatical knowledge nor improves students as writers. In fact, isolated direct grammar instruction tends to impact negatively student writing:

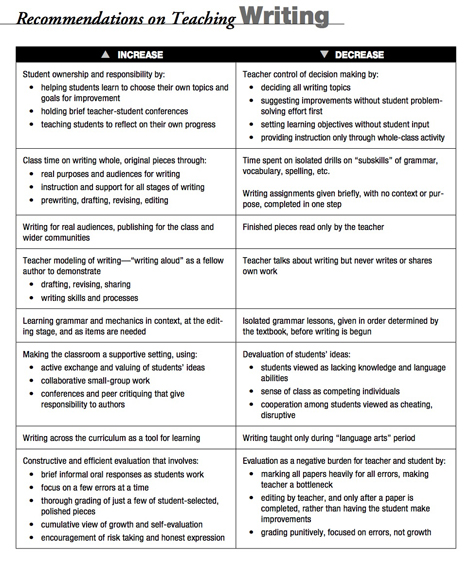

Poniscio’s knowledge-based view of acquiring grammar and his mischaracterization of writing workshop are powerfully refuted by what we know is best practice in writing instruction:

As the chart above shows, best practice in writing instruction is not a template, but a range of practices that must be navigated by teachers and students dedicated to students becoming writers. If Poniscio failed his students when teaching writing, he can point to many things I am sure, but writing workshop properly implemented is not one of them.

Ultimately, we must admit that Brunetta and Poniscio are right about the lingering failure of teaching students to write. To answer why, both Brunetta and Poniscio offer valuable insight, but for different reasons.

Over the past thirty years, high-stakes accountability and testing have ruined the promise of best practice begun in the first days of the National Writing Project in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Standards-and-test mania have supplanted a rich field of teaching writing, one that is still evolving and one that remains characterized by tensions.

But a second reason we continue to fail the teaching of writing is that English teaching has a long history, as I quoted LaBrant above, of allowing a ”considerable gap between the research currently available and the utilization of that research in school programs and methods.” This professional failure has occurred even when the stakes were not high or linked to standardized tests.

Writing remains a powerful and important tool for learning, thinking, and expression. The teaching of writing, although often marginalized and ignored, should be foundational to all education—although it remains a distant cousin to reading and math.

Continuing to seek new standards and better tests will only erode further the failure to teach writing Brunetta and Poniscio identify. Instead of trying to close the achievement gap measured by test scores we have manufactured during the accountability era, we are way past time in our need to address the gap between what we know about teaching writing and what we do with students in our classrooms.

For Further Reading

- Writing Instruction That Works: Proven Methods for Middle and High School Classrooms, Arthur N. Applebee and Judith A. Langer

- The Testing Trap: How State Writing Assessments Control Learning, George Hillocks

- Teaching Grammar in Context, Constance Weaver

- Teaching Writing As Reflective Practice: Integrating Theories, George Hillocks

- Best Practice (4th ed.), Zemelman, Daniels, and Hyde

- Research on Composition: Multiple Perspectives on Two Decades of Change, Peter Smagorinsky, Editor

Paul L. Thomas is an associate professor of education at Furman University.

This essay was reprinted by EmpathyEducates with permission or license from the Author.

Leave A Comment