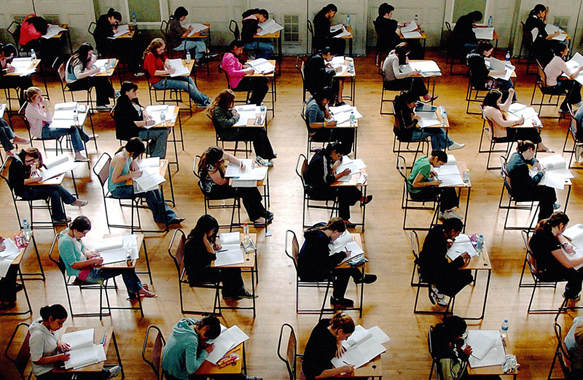

Photograph; Rui Vieira / PA Wire

By Owen Davis | Originally Published at Salon. AlterNet. February 4, 2014 8:30 AM

The next 12 months will determine whether privatizing trends of the last decade are reversing or merely stalling

For people looking to “disrupt” public education, it’s become requisite to bemoan the “educational status quo” — a phrase meant to evoke images of poor kids striving against the impediments of failing schools and incompetent teachers. Those who question these disruptors’ methodologies are cast aside as hidebound intransigents who likely have some vested interest in an ossified order.

But as a report from Bolder Broader Approach, a progressive advocacy group, noted last year, a new “status quo” has not so quietly taken root. “A popular set of market-oriented education ‘reforms,’” such as test-based teacher evaluation and public school choice, “look more like the new status quo than real reform.”

After more than a decade, such reforms have become the norm, and efforts to reverse them are no longer acts of resistance but of upheaval. While 2013 saw unprecedented boycotts of standardized testing, 2014 will see the implementation of the first coast-to-coast standardized tests aligned with the Common Core. Economic inequality has again become part of the education conversation, as states continue to cut funds for schools.

In 2014, several new and ongoing education battles will show whether the privatizing trends of the last decade will reverse in the years to come or simply stall. In courthouses, statehouses, and school communities nationwide, larger trends and crucial precedents are coming into view. These five stories will help define the shape of education to come.

The Sharp End of the Common Core: Assessments

By now everyone has a word to say about Common Core State Standards, the federally funded, foundation-backed set of “rigorous” and “internationally benchmarked” curriculum guidelines developed to make test scores comparable—and educational gewgaws marketable— across state lines. But fewer people can name the two testing coalitions tasked with bringing these standards in multiple-choice form to classrooms in 42 states this year.

These new assessments won’t come cheap or easy. The entirely computer-based new tests require costly technical capacities that many schools lack. For more than half of the coalitions’ states, testing costs will rise. By the coalitions’ own estimates, students will spend up to ten hours cumulatively at the testing screen.

The Common Core gets cast a monolithic entity, but it wouldn’t be a free-market reform if the undertaking weren’t composed of massive federal initiatives, dozens of interlocking nonprofit participants, diffuse state-level coalitions and scores of well-recompensed contractors. While the standards themselves were developed by two coalitions of state executives, the design and implementation of new tests has become the province of two new organizations: PARCC (the Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers) and SmarterBalanced.

The Department of Education granted the coalitions a combined $330 million to develop computerized tests aligned with the CCSS. Each in turn subcontracted its test design and technological components to a bevy of private contractors. As is usual in matters Common Core, the professional connections and ulterior interests between the nonprofits, consultants and hangers-on approaches a level of complexity on par with quantum physics.

The tests emerge from this morass ready for implementation in 2014-2015. But several deep-red states facing mounting Common Core backlash, most recently Alaska, have backed out of the coalitions. Florida cited “excessive involvement by the United States Department of Education” in its decision to withdraw. But the new assessments will also meet a burgeoning, mostly progressive movement of parents and educators committed to opting their kids out of standardized tests in record numbers this year.

Reaction to these new tests, from how many states pull out to how many students opt out, will influence the fate of both the Common Core standards and US standardized testing.

Fairness in Funding Lawsuits

A landmark civil rights lawsuit in Connecticut took a decade to wend its way through the judiciary up to the state’s Supreme Court, and it’s lingered there for years. But the case, scheduled to be heard in 2014, could set the tempo for funding equity battles in years to come.

Connecticut, the second most unequal state in the union, provides a perfect test case for school funding. Resource gaps there manifest in crumbling libraries, nonexistent after-school activities, overstuffed classes, inadequate special education services, obsolete technology. After meticulously documenting these and other disparities, lawyers and Yale law students launched the Connecticut Coalition for Justice in Education Funding. In 2005 they filed CCJEF v. Rell, arguing that the state’s constitutional guarantee of free public education necessitates attention to equity, taking special aim at the state’s regressive funding formula.

The case exemplifies how mainstream Democrats in the last decade have dropped equity concerns to pick up the torch of free-market reforms. One of the case’s original plaintiffs was Dannel Malloy, current governor of the state. Then an equity-minded liberal, he’s since passed schools legislation that implements test-based teacher evaluations and creates a “commissioners network” of schools unburdened of democratically elected school boards.

Malloy’s top attorneys recently filed for the case to be dropped, reasoning Malloy’s reforms sufficiently addressed school funding. But as Connecticut education advocate Wendy Lecker pointed out, those piddling reforms sent an additional $209 per pupil in Bridgeport, where CCJEF’s calculations suggest adding $7,505. New Britain got a measly $245 per student on $10,185 owed.

The court rejected the state’s request to block the lawsuit. If the court decides in favor of the CCJEF, it would signal a defeat of the new reformer Democrat at the hands of the social justice Democrat. More substantively, it could bring funding imbalances more in line with the needs of students, as lawsuits in Texas and New Jersey have done recently and in the past. In an era of historic state cuts to education, this kind of lawsuit will become increasingly consequential.

Federal Education Policy: Left Behind

2014 was the deadline by which No Child Left Behind demanded universal proficiency on standardized tests. Halfhearted attempts to head that deadline off with a reauthorization of federal education law bubbled up in both the House and the Senate last year, and it’s remotely possible that a full bill will emerge in 2014. But in the final year of No Child Left Behind’s purview, inaction could be a policy in itself, further empowering the Department of Education to pursue its own priorities.

Originally passed in 1965, the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) customarily comes up for reauthorization every five years. In its latest iteration in 2002, Congress decreed that every kid in the country would be “proficient” in math and reading within twelve years. Following the logic of vegetable breeders, they empowered states to pluck out any school coming up short on standardized tests and plant another one in its place until only high-achievers remained. After millions of standardized tests and over 15,000 school closings, those lofty goals remain distant and the woefully outdated ESEA, now called No Child Left Behind and expired in 2007, remains on the books.

Separate House and Senate reauthorization proposals of 2013 suggest a waning of the era of educational bipartisanship. The Democratic Senate bill includes robust equity benchmarks and allows more state flexibility in assessment and school turnaround. The Republican House, meanwhile, renewed its mania for dismantling anything that smacks of a federal government, a pivot in GOP education politics from broad, top-down accountability policy to a firm states-rights approach. The House’s bill would grant statehouses authority to design education standards, implement merit pay and dole out funds for vulnerable student populations.

Despite their differences, each bill retained the current assessment regime and school turnaround model, the basic architecture of free-market reform. Senate education committee chair Tom Harkin stressed that despite surface differences, both bills draw on the same basic processes: standardized testing in grades 3-8 and high school, and subsequent sanctions.

Messy politics make passage of a complete education bill in 2014 unlikely, thanks in no small part to the educational activism of 2013. Any bill faces especially long odds in the House, where conservative incumbents face fuming Tea Partiers convinced the Common Core is a secret Communist coup. Moreover, the Obama administration began issuing waivers in 2011 allowing states to wiggle out of NCLB’s ironclad demands, provided they accept Obama’s pet reforms (notably, test-based teacher evaluations). All but seven states have received waivers.

That leaves the patchwork of NCLB and Obama waiver requirements the predominant federal education framework. Silence from Congress would further empower the federal Department of Education to chart the course for public education in the years to come. Race to the Top and NCLB waivers have both proven remarkably successful in prodding states to adopt favored policies. Admiring as it is of measures like mayoral control that limit democratic input in school governance, the Department presumably won’t mind steering the ship by itself.

InBloom’s Last Stand

Just as NSA leaks were inflaming the civil liberties community last year, educators and parents learned about inBloom, a sprawling multi-state effort to harvest and centralize student data for companies that contract with public schools. The national database would include not just names and addresses, but sensitive information such as test scores, attendance records, race, disability, economic status and discipline history, among hundreds of other data fields.

After a hundred-million-dollar launch courtesy of the Gates Foundation, the initiative has dwindled from nine participating states to an uncertain three. Even in its stronghold New York, it faces a lawsuit spearheaded by indefatigable parent-advocate Leonie Haimson. The state begins uploading student data by April 1.

It’s a Thermopylae moment for the initiative, whose implementation has been tone-deaf at best. Parents in early-adopting states were understandably aghast that authorities planned to relinquish their children’s information to the cloud without any parental input. With communities unmoved by claims that the database would “tailor the learning experience to suit each student’s needs,” resistance grew strong enough for Chicago, Georgia and Colorado, among others, to renege on their inBloom plans.

The technology was developed by Amplify, a division of NewsCorp helmed by the well-connected former New York schools chancellor Joel Klein. Naturally, inBloom tops the list of Bill Gates’ favorite education “startups,” as it embodies his conviction that data and measurement alone will “lead to vast improvements” in education. According to Khaliah Barnes of the Electronic Privacy Information Center, though, students are “currently subject to more forms of tracking and monitoring than ever before.” A 2013 study found that most states left open the use of student data for advertising, failed to abide by the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, and left kids “unprotected from data misuse, improper data release, and data breaches.”

Even if the inBloom effort withers, Big Data won’t give up on the gobs of money to be made from harnessing student information. Investment by giddy venture capitalists in data-driven education products multiplied seven-fold last year. As NewsCorp’s Rupert Murdoch said when he purchased the company that created inBloom: “When it comes to K through 12 education, we see a $500 billion sector in the US alone that is waiting desperately to be transformed.” The success of Murdoch’s inBloom will send a signal to the droves of data hucksters in the wings, similarly desperate for a chance to transform education.

Boom Year for Charters

Though the winds behind charter schools have been less certain of late, their ranks are set to increase in several large states with already minimal oversight. In Michigan, where 80% of charter schools are for-profit, charter operators with spotty histories are opening new schools across the state. New legislation would expand charters in Pennsylvania, despite a spate of high-profile charter scandals. The biggest charter boom will come, appropriately, from Texas, where the legislature raised the charter school operator cap by 50% to 305. (That’s operators, not schools—the state currently boasts 506 charter schools and 209 operators.)

Charter schools run independently of districts but soak up state and federal student funds. Some are for-profit, some are named for celebrities, some embezzle millions of dollars, and some are perfectly decent. As with public schools, their quality can vary tremendously.

North Carolina also looks ready to grow its charter corps, and proposals would make it the largest expansion there since the late 90s. Its slated policy changes highlight two growing issues in charter school policy: the usually negative influence of allowing multiple authorizers, and the draining of funds from public school districts

Increasingly, states have sought to swell their charter ranks by allowing multiple authorizers to grant charters, just as North Carolina has done. Imagine legislation that spread the authority of the FDA to universities, appointed panels and even independent nonprofits, permitting groups of various prerogatives to inspect beef and run drug trials. You wouldn’t be surprised to see subsequent E. Coli outbreaks and sudden drug recalls. Predictably, in the 20-odd states with multiple authorizers, charter quality suffers even as their numbers increase.

Meanwhile, public school districts across the country are facing the same plight as Durham, North Carolina, which claims to be losing $14 million a year to charter schools. East Baton Rouge, could lose as much as $22 million annually to a charter sector which added five new operators this year.

Some charter proponents see no problem in that. When public education becomes a marketplace, competition isn’t just possible but guaranteed. The system has reached its limit in places like New Orleans, though, where over 80% of students attend charters and the promises of reform have foundered. There, a lawsuit filed by families of students with special needs will move forward this year. The plaintiffs contend that the heavily charterized Recovery School District “systematically den

Even before Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans has set the pace for free-market education reforms. Though it doesn’t seem likely that four-fifths of US school children will attend charters any time soon, what happens in the Big Easy becomes a bellwether for future trends. If the poster-child of charter-school reform systematically excludes its neediest students, proponents of the notion that the marketplace will heal education will have some uncomfortable questions to answer this year.

Leave A Comment