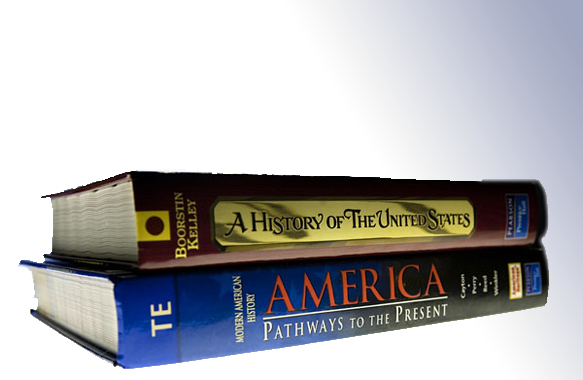

Photograph; “A History of the United States” and “America: Pathways to the Present,” by different authors, use substantially identical language to cover several subjects.

By Betsy L. Angert | Originally Published at Daily Kos. and BeThink. July 14, 2006

No matter where you read it or who has said it, not even if I have said it, unless it agrees with your own reason and your own common sense. ~ Buddha

Authors and academician whose names appear on the textbook cover do not pen what is within. Dead authors do. Ghostwriters compose even more; their contributions are expansive. These indistinct individuals construct a convention. Then we, a trusting public, accept what these unknowns inscribe. What most of us believe is valid is not a universal veracity. Things change in the translation, much to the chagrin of noted authors.

When told that text within his book, “America: Pathways to the Present,” was essentially the same as that found in “A History of the United States,” written by the Pulitzer Prize-winning Historian Daniel J. Boorstin and Brooks Mather Kelley, author, Historian Allan Winkler, stated “They were not my words.” He continued, “It’s embarrassing. It’s inexcusable.” Yet, he excused it.

.

Professor Winkler said he understood the editorial perils of textbook writing, but wanted to reach a wider audience. He said he was not motivated by money. Named authors share royalties, generally 10 to 15 percent of the net profits, on each printing of the text, whether they write it or not.

Allan Winkler, a Historian at Miami University of Ohio, who supposedly wrote the 2005 edition of “Pathways,” book with Andrew Cayton, Elisabeth I. Perry, and Linda Reedr, was now making history, though not necessarily writing it.

According to The New York Times, much of the text offered in the 2005 high school editions of each of these history textbooks was identical. In discussing the September 11, 2001 tragedy or the Persian Gulf wars the verbiage was effectively the same. We might conclude history no longer guides our textbook writings; power and money do. Surprise! Significant stories of eons gone by now must be short, sweet, and yes, even stup**.

The American Textbook Council reports, the problem is

what educators, critics, and journalists informally refer to as “dumbing down.” Many history textbooks reflect lowered sights for general education. They raise basic questions about sustaining literacy and civic understanding in a democratic society and culture. Bright photographs, broken format and seductive color overwhelm the text and confuse the page. Typeface is larger and looser, resulting in many fewer words and much more white space. The text disappears or gets lost. Among editors, phrases such as “text-heavy,” “information-loaded,” “fact-based,” and “non-visual” are negatives. A picture, they insist, tells a thousand words.

What appears in black, white, and is read all over is not as it appears.

Authors are not as noted, and facts are flimsy.

As editions pass, the names on the spine of a book may have only a distant or dated relation to the words between the covers,

This according to people within the publishing industry. Authors themselves make similar assertions.

Again, the American Textbook Council states,

Textbook content is thinner and thinner, and what there is, it is increasingly deformed by identity politics and pressure groups.

Apparently, Political Action Committees produce much of the literature. Politicians exert their power; they want those with these groups to vote for them. Money and the market are influential. A contract with a major school district is worth tens of millions of dollars in profit. If a State Department adopts a textbook series, the bucks will surely pour in. Publishing is a business and we know businesses have their own self-interest at heart.

Asking academicians to document a dynamic occurrence or two can deplete profits, and that would not be economically wise. Therefore, it is rarely done anymore. Historians may write the first edition, from there on, no one knows who authors a text.

Professor Winkler, one of the authors of “America: Pathways to the Present,” said he and his co-authors had written “every word” of the first edition, aiming to teach American history from a sociological perspective, from the grass roots up. But, he said, in updated editions, the authors reviewed passages written by freelancers or in-house writers or editors.

He said the authors collaborated on their last major revision before Sept. 11, 2001, working with editorial staff members in Boston. But he said that after the attacks, he was not asked to write updates and was not shown revisions.

“There was no reason in the world to think that we would not see material that was stuck in there at some point in the future,” Professor Winkler said. “Given the fact that similar material was used in another book, we are really profoundly upset and outraged.”

However, this practice is not a new one.

Susan Buckley, a longtime writer and editor of elementary and high school social studies textbooks who retired after 35 years in the business, said that “whole stables” of unnamed writers sometimes wrote the more important high school textbooks, although in other instances, named authors wrote the first editions. In elementary school textbooks, Ms. Buckley added, named authors almost never write their own text.

She said even if named authors did not write the text, they had an important role as scholars, shaping coverage and reviewing copy.

What that role might be is illusive. It escapes many that read of this situation.

Nevertheless, the concept and customs do not go unnoticed. The watchful eye of William Cronon, a Historian at the University of Wisconsin, Madison is aware of what is happening in the textbook publishing world. Mr. Cronon authored the statement on ethics for the American Historical Association.

He said, textbooks are corporate-driven collaborations efforts. The publisher governs the market. They have well-defined rights to hire additional writers, researchers, and editors. They may make major revisions without the authors’ final approval. The books typically synthesize hundreds of works without using footnotes to credit sources. The reason for these declaratory privileges is profit and a conciliatory stance to those in power.

Professor Cronon affirms,

“This is really about an awkward and embarrassing situation these authors have been put in because they’ve got involved in textbook publishing.”

Textbook publishing is an industry like all others; the driving force is the desire to increase earnings. Publishers must be innovative, imaginative; yet, they need not be truly instructive. It is assumed educators will do that. The printers of textbooks create a market regardless of a need. Publishing houses know they have a captive audience. Curriculums change little from semester to semester. However, the text is altered regularly. The publisher must create a demand so that they can offer a supply. They have bills to pay.

In a recent Washington Post article, Textbook Prices On the Rise, journalist Margaret Webb Pressler reported,

the California Student Public Interest Research Group found that the average release time between textbook editions is 3.8 years, regardless of whether the information has changed since the previous version. Of the textbooks surveyed, new editions cost 58 percent more than the older version, rising to an average cost of $102.44.

Publishing corporate bigwigs cut corners as they relate to production and quality; however, they never lower the prices. School districts know this, as do college students. Again, according to the Washington Post,

The National Association of College Bookstores says wholesale prices of college textbooks have risen nearly 40 percent in the past five years. And students are finding that many of the same books are sold overseas at much lower prices.

Yes, textbook publishing is quite beneficial. The printer of these volumes realizes great earnings. Textbook writing can also be quite a prize; authors satisfy their yearnings. A textbook writer may achieve fame and perhaps, further his or her fortune. Allan Winkler acknowledges this.

“I want the respect of my peers,” Professor Winkler said. “I’ve written monographs, biographies,” but these reach a limited audience. “I want to be able to tell that story to other people, and that’s what textbooks do.”

Schoolbooks do tell a substantial story, though it may not be the tale Mr. Winkler or we expected.

Thus, I ask again, “Who writes our history?” The answer is, publishers, guided by profits, politicians promoting favorable policies, pressure groups, then historians. After all, Historians seeking acknowledgment from their peers do submit their anecdotes; however, these contributions are less important. Over time, historical accounts will be lost, just as our past is. Apparently, profits and power are our only presents [presence.]

Read What is Written, if you choose . . .

- Schoolbooks Are Given F’s in Originality, By Diana Jean Schemo. The New York Times. July 13, 2006

- American Textbook Council.

- Testimony of Gilbert T. Sewall, U.S. Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee hearing. American Textbook Council. September 24, 2003

- Textbook publishers should put people before profits, By Jesse Hicks. The Pitt News. February 4, 2004

- Textbook Prices On the Rise, Frequent New Editions, Supplemental Materials Drive Up Costs, By Margaret Webb Pressler. Washington Post. Saturday, September 18, 2004

- Frequently Asked Questions About Textbooks The Association of American Publishers (AAP)

- Directory of Publishers and Vendors, Education Publishers, AcqWeb.

- Getting Started Creating A Textbook, By David A. Rees, Southern Utah University. Society of Academic Authors.

- When Government Writes History, A Memoir of the 9/11 Commission. By Ernest R. May. The New Republic. May 16, 2005

Leave A Comment